The fourth reason detective mysteries are appealing as stories is related to the foundational truth that human existence is meaningless apart from community. We do not thrive nor are we fully content as solitary creatures, because as the Creator said in the beginning, it is not good to be alone (Genesis 2:18). Extended solitary confinement can drive a person mad, and even hermits usually build their cells near one another.

And because we are finite and fallen creatures, as soon as community is established a system of some sort is necessary if justice is to be maintained. It may be a simple system that grows up informally, but something systematic is required if the community is not to descend into some sort of libertarian anarchy. This is the wisdom in Jesus’ instructions to his followers about how to proceed if someone sins against us (Matthew 18:15-20) and when churches fail to take his words seriously the result is rarely admirable.

And because we live in a broken world, corruption can penetrate our systems, within the church or without, and when it does all of life is disrupted and perverted. Sadly, corruption is a constant threat, from cities where the police accept bribes to look the other way to the incestuous relationship between Washington and Wall Street. Corruption undercuts the pursuit of justice, skewers the hope of victims, and allows the powerful to gain at the expense of the powerless.

Detective stories bring this complex interrelationship of community, system, justice, and corruption into focus so that as we read life seems to be clarified. We love detectives who are incorruptible, and see them as heroic. We wonder about the detective who takes shortcuts for the greater good, and cheer if their breaking the rules results in the criminal being apprehended. And we feel a weight when the story is of corruption all through the system, so that justice is always thwarted and the forces of law instead make a bargain with the forces of crime to keep the evil within “acceptable” limits. This is why debates about a nation’s judicial system become so heated—even if we are not dragged into the justice system personally it matters to us that the system in our community is not corrupted.

And so detective stories are appealing because they allow us to live in a fictional world where these realities are explored, for blessing and for curse. We follow the cases of incorruptible detectives and feel hopeful, or the cases of corrupt detectives and wish they would be caught and exposed. Human community, systems of law and order, and the diabolical threat of corruption are constantly with us, and both justice and hope lie in the balance.

Lord Peter & Father Brown

If you have not read Dorothy Sayers’s (1893-1957) Lord Peter Wimsey mysteries or G. K. Chesterton’s (1874-1936) Father Brown mysteries, please do so. I think it is correct to say that these two Christian authors not only wrote ripping good stories, they revealed how glorious the detective genre could be.

Lord Peter is a stereotypical British aristocrat, with a trusty butler, and time on his hands because his money, which is considerable, was inherited. So he solves mysteries, and because of his moral commitments and lack of need, is incorruptible in his pursuit of justice. An interesting detail for Christians is that though Lord Peter is not a believer, another character in the stories is, and the interplay between the two is fascinating.

Father Brown is a Catholic priest, and is a good detective because he cares only for truth and has spent so many hours hearing confession that he has no illusions about human nature. He can see past and through deception and lies, and notices ordinary details that more distracted people all miss. When he confronts the criminal at the end of the story it is not with the standard, “You are under arrest,” but with “I am ready to hear your confession.”

Both Sayers and Chesterton clearly saw how detective stories fit into the deeper biblical story of reality, and though neither series are religious in the sense of being preachy, both take law, guilt, justice, mercy and forgiveness with the seriousness they deserve. The fact that neither detective is corruptible makes the stories all the more satisfying. I’d like both Lord Peter and Father Brown to be at work in my community.

Father Brown (51 short stories published in various editions).

Lord Peter (11 novels plus 6 short story collections published in various editions).

The Protectors

The Danish national police force includes the P.E.T (Politiets Efterretningstjeneste) division, whose job is similar to that of the U.S. Secret Service, providing protection to politicians, public figures, royalty, and visiting diplomats. The series follows a group of new recruits to the service, so we get a glimpse of the more mundane as well as the exciting parts of the job. The individuals on the squad have personal lives and concerns, and how these interact with their demanding and dangerous work is a subtext woven into the plot.

In one sense The Protectors is not a detective series, yet fulfilling the tasks assigned to them usually involves needing to anticipate dangers and unravel threats to the persons they must keep safe. Their work carries them to the edge between criminal violence and social justice, and hidden clues and mysterious criminals always lurk. And they are tasked with preventing terrorist attacks, tracking dangerous persons, and finding stalkers.

One of the delights of The Protectors is the insight it allows into Danish life and society. Filmed in Copenhagen, each episode provides lovely vistas of Danish countryside or the scenic streets, architecture, interiors, and neighborhoods of Copenhagen. Following the members of the squad also allows insight into Danish culture, mores, and daily life.

I enjoyed this series, appreciated the character development as the episodes progressed through each season, and came to understand how even working as a bodyguard can demand choices that are rife with ethical concerns, and sometimes moral confusion. The Protectors are often misunderstood, criticized when things go badly by powerful figures in politics and the media, and ignored when everything goes well. Yet the squad remains committed to its work, and does its best even when needing to protect unsavory characters. In a fallen world, police like the P.E.T. will always be necessary, and one can only hope that they act with the integrity the officers in The Protectorssought to nurture and display.

The Protectors (2 seasons, 10 episodes each, 1 hour each episode, Danish with subtitles, available on DVD or streaming)

Spiral

The Protectors is set in Denmark and follows a squad of limited officers who desire to live with integrity, while Spiral takes us to France where nearly everyone depicted in the series seems willing, if not eager, to be corrupted to get ahead. Spiral is delightful for the opportunity it provides to see into French life, society and culture and the lovely setting of Paris. The corruption comes not because they are French, but because they are fallen, and to mark the contrast, one figure in the series seeks justice even at personal cost.

The French system of justice is quite different from what I am used to, with magistrates empowered to investigate crimes and determine whether the persons involved should be brought to trial. The series follows one such magistrate and the police working under his direction depicting how he must weave his way through a labyrinth of political vested interests and legal corruption. Two young attorneys, trying to get their careers launched in a crowded and competitive field, discover the temptation to bend the law is not merely present but is usually far more lucrative than just doing the job of a lawyer.

The depiction of corruption is never glorified, and though characters may claim things are relative, the stories reveal that is not the case. Choices have consequences, justice perverted is never victimless, and the individual who chooses corruption may gain wealth and even prestige but loses their soul.

Each series of episodes tends to follow one major crime, as it is investigated and brought to justice, with subplots of other smaller cases woven into the plots. Over time we watch as temptation, disappointment, and choices make a difference, setting up ripples that work their way out to poison the system upon which the community depends. This is a rather dark and gritty series, one that shows not just the horror of crime, but the tragedy that is corruption.

Spiral (5 seasons, 8-12 episodes each, 1 hour each episode, on DVD and some streaming, French with subtitles)

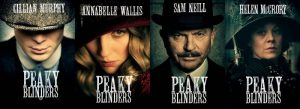

Peaky Blinders

A production of BBC Two, Peaky Blinders tells the story of a family gang that ruled the streets of Birmingham, England in 1919. World War I has just ended, conditions for working men in Birmingham are grim, Communist agitators are seeking to organize resistance, industrial pollution is unrestricted, and despair and alcoholism are rampant. The Peaky Blinders, a family of gangsters are named for their caps, into the peaks of which they have sewed straight razors, so in a street fight they can be slashed across an opponent’s eyes. The neighborhoods that the gang rules are bereft of law, the police either bought off or too afraid to get involved. Then the brutal but effective Chief Inspector Chester Campbell (played by Sam Neill), is brought in from Belfast by Winston Churchill to clean up the mess, and he soon comes up against the head of the Peaky Blinders, the clever and ambitious gangster Tommy Shelby (played by Cillian Murphy).

In this series we go one step further and watch what life is like when corruption has perverted the system, so that the street gang and the police are more alike than not. Both take life when it suits them (though for different reasons), make compromises to get ahead, and try to find a way to further their own ends even if integrity is lost in the process.

In some neighborhoods today residents fear a squad of police arriving on their street even more than they do the gangs that rule the street when the police are absent. Peaky Blinders gives some hint of what that must be like, and it is not as it should be. Chief Inspector Campbell is on the side of law and order, yet is willing to brutalize, torture, invade homes, and make the sight of a constable a reason for the law abiding citizen to fear.

The trajectory from Lord Peter and Father Brown to The Protectors to Spiralto Peaky Blinders follows stories of increasing corruption. None of these productions glorify crime and corruption but force us to face the reality of the tragedy of living in a darkly fallen world. They reveal how badly we yearn for a system within our communities that seeks justice with integrity, which in turn reveals why we mean it when we pray, “Thy kingdom come, they will be done on earth as it is in heaven.”

The Peaky Blinders (2 seasons, 6 episodes each, 1 hour each episode available exclusively on Netflix and DVD)

And here is where I taper off. I felt anxious, even as I read the descriptions of these shows, and the fallen world I inhabit. I did watch MIV, which like Spiral, (I imagine,) is a detective series of sorts. It was interesting to me in the way modern technology comes in to play. But, I find that my interest in a series quickly wanes when it is not tied up in a nice bow. Maybe that is a short-coming on my part. When the corruption seems never-ending, I bow out. I wonder what that says about me. I do love Father Brown and Lord Peter Wimsey. I appreciate your observations.

I also appreciate, and must ponder how we live in community. These stories highlight how community functions. I will have to think more on that. Thanks again!

Cassandra Egan

Thank you for such a thoughtful comment, Cassandra. You raise an important issue: we do not have unlimited time for fiction and film, and so must choose what to read/watch. I've had friends who could not watch films that honestly unpack the brokenness of the world because they felt they faced too much of it in daily life and so needed something more hopeful on Friday evenings. My wife declines to watch films that hint at supernatural darkness because the images have tended to trigger nightmares. There are plenty of good reasons to "taper off" and "bow out" as you put it, and we should encourage one another and support each other in such decisions.

The only way I think this can can be problematic is if someone declines in an ongoing effort to ghettoize their life so that they live blissfully apart from the brokenness around them. Just as some people use drugs or busyness to keep from facing the hard things of life and reality, it's possible to construct a life that is the equivalent of tiptoeing through the daisies and never having to face the fact that poison ivy exists. There is nothing wrong with sentimental movies (I love the film "Harvey" starring jimmy Stewart) unless they are a part of an intentionally blind, sentimental perspective on life.

So, Cassandra, your choice meets no resistance from me. Margie has often commented that she likes the fact that my calling means she doesn't have to read books or watch films she'd find distasteful but that she appreciates knowing about. That's OK with me.

Know grace today, and thanks, as always, for commenting.

Denis