This past week I witnessed the consecration of an Anglican bishop. Ordinations always fill me with a sense of wonder, because they are moments in time in which eternity breaks in and realigns reality. As I expected, Anglicans use words in the consecration, words of scripture and long tradition. They also use actions. We are physical creatures, so actions help make spiritual truths real. In the consecration of an Anglican bishop there is the laying on of hands, of course, but another action caught my attention. I had not seen it before.

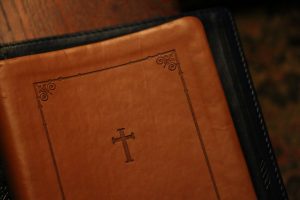

During the consecration the archbishop presented the new bishop with a copy of the Bible. He did so by first holding it over the man’s head. “Give heed to reading, exhorting, and teaching,” the archbishop said. “Think upon the things contained in this Book. Be diligent in them.” Only then did he lower the book and hand it to him.

I loved the imagery of holding the Bible above his head. It was a striking demonstration of submitting to scripture, placing oneself under its authority. This should be my posture as well. If I believe the scripture to be God’s revelation, I need to be under its authority as well.

But today living under authority isn’t embraced fondly. The notion smacks of rigidity, of acquiescing instead of thinking independently, of blindly following tradition instead of pursuing facts. Submitting to authority we are told—especially religious authority—means substituting unyielding dogma for the openhearted and open-minded pursuit of truth.

St. Augustine (354-430) saw the issue very differently. He said that everyone lives under authority and the only thing left to determine is what authority we choose to trust.

Think of it this way. We all believe all sorts of things and yet have personally proved almost none of them. I believe the hydrangeas in my yard need phosphate to grow well but I’ve never done a double-blind study on it. When I see the northern lights I believe the “Auroras are produced when the magnetosphere is sufficiently disturbed by the solar wind that the trajectories of charged particles in both solar wind and magnetospheric plasma, mainly in the form of electrons and protons, precipitate them into the upper atmosphere (thermosphere/exosphere), where their energy is lost.” I believe that but not only have I never proved it I don’t even know what that sentence means. And so it goes. Take any part of life, and see just how much of it you have actually, carefully and thoroughly proved, and you’ll quickly see the truth of St Augustine’s claim. We believe a great deal about a great deal, and we accept almost every bit of it on the basis of some authority. “Nothing would remain stable in human society,” he wrote, “if we determined to believe only what can be held with absolute certainty.”

The whole idea takes on added significance, of course, when considering the things that matter most, on the deepest yearnings of the human heart, on questions of meaning, purpose and reality, of life and death. Which authority am I convinced is most trustworthy? Which book do I take my stand under? In what do I place my faith?

Different people give different answers to this question, and the public square is crowded with competing claims. I want to listen carefully to them, because my love of Jesus makes me passionate for the truth.

For myself, however, I agree with the Irish believers who long ago wrote a hymn to glorify the High King of Heaven. “Be thou my wisdom / And thou my true word / I ever with thee / And thou with me Lord / Thou my great Father / I thy true son / Thou with me dwelling / And I with thee one.” In the story told by poets, prophets and apostles in Holy Scripture and fulfilled supremely in the living word, Jesus Christ, I find the most satisfying, plausible and compelling vision of life and reality.

So, this morning I stood in my office and held my Bible over my head. No one noticed but God, but that was the point.

![]()