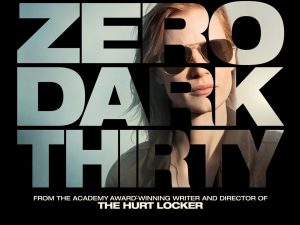

Zero Dark Thirty (Kathryn Bigelow, 2012)

A discussion worth having

From the beginning art has shown itself, in all its multiple forms, to be a window of insight into the deepest recesses of meaning and significance in life. It helps us see with greater clarity the nature of reality, and without art we find ourselves dehumanized and less certain of our place in the creation. Good art invites us into conversation with the artist about things that matter most.

Sometimes in this conversation the work of art raises questions explicitly. One example is the 1897 painting by Paul Gauguin. If we read the work from right to left we see images of women, from an infant on the right, though the flowering of youth, into middle age, ending with an elderly figure on the left. And in case we might miss his meaning, the artist includes three questions in the upper left hand corner: “Where do we come from? What are we? Where are we going?” They are good questions, important questions, questions every generation, individual and culture must address, and which we still struggle with today.

Most of the time, however, the conversation in art involves work that raises questions implicitly. What is imagined here? Do I see a bit differently as a result? Still, whether explicitly or implicitly, questions are raised as part of the rich expression of human creativity.

The questions we ask are essential milestones on the path to finding truth and goodness, both as a society and as individuals. Film is particularly good at raising questions, and the best films do so with great power if we have ears to hear. Unlike any other art form, movies blend story, dialogue, and music with audio and visual effects so that questions are not just raised, but are set loose in a social context that tends to naturally provoke conversation and discussion.

Kathryn Bigelow’s film, Zero Dark Thirty (2013) has gained a lot of media attention for raising uncomfortable questions. It is, as the story of the killing of Osama bin Laden, a film with an entirely predicable ending. Nevertheless it manages to hold our attention through gritty realism and superb craftsmanship. Set in recent history, it seems larger than life because it simultaneously records an American victory, serves as a witness to an American tragedy, and reminds us of a questionable episode of American ethics.

Bigelow has come in for a lot of criticism because she included scenes of torture in the film. Prisoners are subjected to vicious beatings, waterboarding, forced nudity before members of the opposite sex, prolonged sleep, water, and food deprivation, and threatened with attack dogs, among other things. Some critics have maintained that Zero Dark Thirty asserts that these so-called “enhanced interrogation techniques” produced intelligence that was helpful in tracking down Osama bin Laden, but that is inaccurate. The film depicts these techniques being used by American agents on terrorist suspects. The film is rather ambiguous in the utility of torture during interrogation, and shows the hunt for bin Laden as primarily involving a very long and frequently frustrating process of careful detective work on an international scale.

Still, Zero Dark Thirty is a troubling film, and one that should prompt serious discussion. The questions it raises—implicitly and at times, explicitly within the dialogue—are important ones that Americans in general and American Christians in specific should not seek to sidestep. These issues are too important to be left simply to secret presidential executive orders. How we answer them will reflect on how America is seen in the world, and will reveal our deepest moral convictions as a society. We need to have a serious conversation in America, but so far our partisan polarization is preventing us from having it. I am grateful to Kathryn Bigelow for producing a piece of art that is powerful enough to catch our attention as a society. I hope we do pay attention and have that conversation. These are questions that define us as a society and a people and touch on ethical issues that get to the very heart of our ideals of justice.

How do we define torture? What is the line between justice and vengeance? If all people are created equal how must even enemies be treated? Is it possible to win against terrorism but lose our soul as a nation? How do we define just war?

The just war tradition goes back to St Augustine (354-430), bishop of Hippo in North Africa in what is today Algeria. Augustine lived as the Roman Empire crumbled, and so the clash of armies in warfare was a reality. He was concerned to think through the topic of war in distinctly Christian categories. In doing so, he developed the theological and philosophical framework for what became the just war tradition, which was to be distinguished from alternatives such as pacifism (a principled adoption of non-violence) or militarism (where a person is merely swept along with the popular societal approval of some conflict).

As it has developed and come to us today, the just war tradition addresses both the justification of going to war or entering some conflict and how to then conduct the conflict in a just manner. There are 5 conditions necessary for justifying a war in the first place:

1. Legitimate authority—it is not for individuals or groups to determine to go to war but magistrates in legal office under law.

2. Just cause—the cause of the conflict must be sufficient to warrant armed conflict as a proportionate response in either defending rights or in an offensive action taken to stop a greater evil.

3. Right intention—the objective must be to establish peace and a love or pursuit of justice, not the hatred of an enemy.

4. Last resort—every possible effort must be made to resolve the issue before resorting to war.

5. Probable success—there must be a reasonable and high probability of success in winning the conflict.

And then the just war tradition identifies two conditions necessary for the just conduct of war itself:

1. The principle of discrimination—the threatening forces must be attacked while the innocent must be spared and protected.

2. The principle of proportionality—the scale of the attack must be kept minimal so that no more damage is to be inflicted than is truly necessary.

The questions raised by the film Zero Dark Thirty are important, and though I am no prophet, the news suggests to me that these issues are not going away any time soon. Those of us who are Christians can be grateful they have been raised because we bear a responsibility to seek justice in our broken world. The Scriptures call us to responsibility, so that as individuals in conversation with friends and colleagues, and as citizens encouraging a conversation on these things in the public square, part of Christian faithfulness in seeking justice involves discerning whether our nation’s policies and wars are just.

Let me suggest four things that need to shape our faithfulness in pursuit of this task, two negatives and two positives.

1. Resist politicization. One reason it is so difficult to discuss these things is because our society—and many within the church—have been politicized. By this I mean they tend to see just about everything in terms of the political process. The test is to bring some issue up and see how quickly someone raises politics. We must resist this as Christians for several reasons. First it is an idolatrous mindset. Everything is related to God, not to politics, which is only a tiny slice of life and reality. Second, politicization undermines the discussion by switching it from a pursuit of the truth and justice to the scoring of points and the taking of sides. And finally, it perverts our perspective by suggesting that politics can solve the deepest problems of the human heart. Rather, politics in a democratic society reflects the hearts of its citizens and leaders. This means that culture is always more influential and important than politics, and the gospel always trumps both culture and politics.

2. Resist cynicism. Challenges like this seem to somehow automatically incite a cynical response today. So remember, we are talking about being faithful not about changing the world. Being faithful is our calling, changing the world is God’s prerogative alone.

3. Be people of prayer. Each week, in our liturgy we recite the Lord’s Prayer. When we pray, “thy kingdom come, thy will be done on earth as it is in heaven” we need to mean it passionately.

4. Seek integrity, credibility and civility. “When asked to summarize the challenge facing the church today,” Os Guinness says, “I often answer that it can be stated in three words: integrity, credibility, civility. First and foremost, we face a challenge of integrity, in terms of whether we are faithfully living out the good news of God’s kingdom in the way Jesus called us to. Second, we face a challenge of credibility, because the educated elites of our day, shaped by the Enlightenment, see us all, in Richard Dawkins’s term, as “faith-heads.” It is time for every follower of Jesus to love God with all our minds, and to show that we think in believing, and that we believe in thinking. Third, we face a challenge of civility, in terms of how we respond to one the world’s greatest issues: how we live with the deepest differences of others. Do we really defend truth with love? Do we truly love our enemies, and do good to those who wrong us? Or do we respond in kind, and join so much of the culture-warring ugliness of our day?”

Even if you don’t enjoy war movies, I urge you to watch Zero Dark Thirty. The questions it raises are too important to be ignored.

May we be found faithful as God’s people to stand for justice, even at cost.