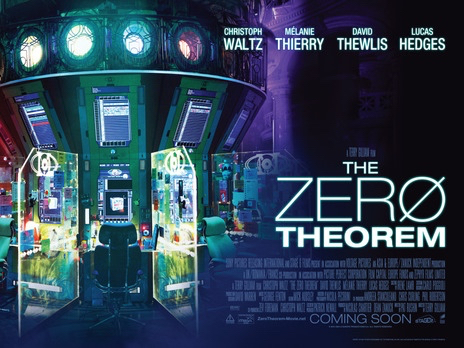

The Zero Theorem (Terry Gilliam, 2014)

What’s the point of anything?

Absurdity, it is said, rests on the knife-edge between comedy and insanity. Those who mistake the absurd for reality are deemed unbalanced, and considered mentally ill or possessed. On the other hand, absurdity in the repertoire of a gifted jester can provoke both laughter and sudden insight by forcing us to see things in a different light.

In ancient monarchies the king held absolute power and his word and whim were law. In such a system to speak against the king was treason, and so the tradition of the court jester was important if truth was ever to be spoken to power. The jester was the only one fully free to speak the truth, as long as the king laughed.

We laugh at the jester but must never underestimate the importance of their deliciously subversive humor in the matrix of human life and society. “Who is wise enough for this moment in history?” Os Guinness asks in The Gravedigger File. “The one who has always been wise enough to play the fool. For when the wise are foolish, the wealthy poor and the godly worldly, it takes a special folly to subvert such foolishness, a special wit to teach true wisdom.” (p. 230)

Even if royals, presidents, and CEOs no longer wield absolute power, the tradition of the jester continues. Charlie Chapman, the Marx brothers and Monty Python were brilliant at taking dialogue, story lines, and visual sketches to absurd lengths. At their best they make us laugh, and then pause to realize some of the laughs are on us.

Sometimes, in taking ideas to absurd lengths they warn of how things may unfold in the future and the insight of their humor assumes a prophetic edge. One such jester is Terry Gilliam, the American member of the British comedy troupe Monty Python. He seems to delight in his gift of taking ideas to their logical but absurd conclusion in order to shed light on the folly that weaves its way through the affairs of a fallen humanity in a broken world.

In 1985 Gilliam wrote and directed Brazil, supposedly set in some future unspecified date in the 20th century. In this absurdist, visionary science fiction film, Gilliam imagined a world in which work seems meaningless; where the quest for youthfulness introduces ever more forms of cosmetic surgery; where technology, advertising, and impersonal bureaucracy are ubiquitous; where democracies excuse torture to extract needed information; and where liberty is happily sacrificed and intrusive police force is tolerated for greater security in the face of random terrorist violence. Sound at all familiar? The consensus I heard in 1985, however, was that Brazil was funny, at least for those who have a taste for Monty Python type humor, but as social commentary it was far too absurd to be taken seriously.

In 2014 Terry Gilliam released another film, The Zero Theorem. It isn’t a sequel to Brazil, but is similar in both genre and intent. You will find the same attention to detail, the deliciously subversive humor, and the wild imagination at work inviting us to look again at life to see what we might have missed the first time we looked. In The Zero Theorem, Gilliam takes the perennial question of meaning in life and asks where the predominant answer proposed by our scientific secular world will take us as we try to find an answer.

We are introduced to Qohen Leth, played by Christoph Waltz, a brilliant computer gamer working for Mancom, a computer/net conglomerate. Qohen lives in seclusion in an abandoned, dusty church waiting for a phone call from management that will tell him the purpose of his life. Though the phone occasionally rings, his call never comes. Outside is a fast changing, fast paced globalized world of constant noise, frenzied activity, intrusive advertising, religious pluralism, and online relationships. He works at an elaborate computer terminal set in the sanctuary of the church, tasked with solving the zero theorem. That is a mathematical equation that will add everything in life and reality up and show the sum to be zero.

“Nothing adds up,” Qohen says to his supervisor, Joby (played by David Thewlis). “No,” Joby says. “You’ve got it backwards, Qohen. Everything adds up to nothing, that’s the point.” “What’s the point?” Qohen asks. “Exactly,” Joby says. “What’s the point of anything?”

The film opens with the image of a huge, swirling black hole, an image that appears repeatedly in the background as Qohen works on the zero theorem. They are close to solving it but Mancom is, as Management (played by Matt Damen) says, “still crunching the data.” Near the end of the film Qohen and Management meet and talk. “Why would you want to prove that all is for nothing?” Qohen asks. “I never said all is for nothing,” Management replies. “I’m a businessman, Mr. Leth, nothing is for nothing. Ex inordinateo veni pecunia.” “What?!” Qohen says. “There’s money in ordering disorder,” Management says. “Chaos pays, Mr. Leth.”

Our secular world proposes that meaning and significance can be found without any reference to the divine or the transcendent. And since in such a world everything is finally indistinguishable from nothing, meaning must be significance must arise out of nothing. Gilliam takes that idea seriously, runs it through his comedic imagination and shows its sentimental absurdity in a way that is really quite stunning. After a lifetime of work to solve the zero theorem, at the end Qohen is left with nothing. “What is the meaning of life, Mr. Leth?” Management asks rhetorically. “So close to its end and still no answers.” And then Management fires him.

I’ll leave you to discover how Gilliam ends the film, and what you think it means.