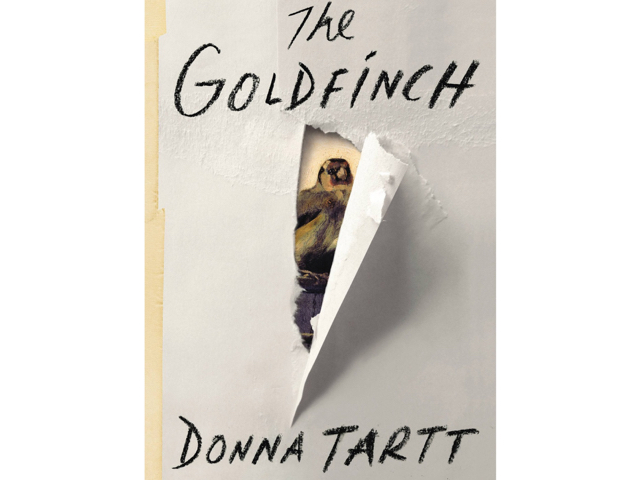

The Goldfinch (Donna Tartt, 2013)

Beauty alters the grain of reality

Imagine growing up having lost your mother when you are thirteen in an explosion at an art museum after your father, a rough drunk, has abandoned the family. You are given shelter, first by the wealthy parents of a school friend and then by your dad and his sleazy girlfriend. You befriend an equally marginalized boy and discover there are ways to medicate your numbness and pass time in an endlessly boring existence.

You finally land in the delightfully cluttered home of a man who restores antiques, and whose artistry, skill, and love of wood and well-crafted furniture are matched with a character of kindness, honesty and integrity. He isn’t a good businessman or salesman, but you are—so good that it’s easy to let smug, self-satisfied wealthy customers assume things about antiques that aren’t true, so that the bottom line of the shop is vastly improved. Imagine too that when the explosion in the art museum tore apart your life you carry out of the museum that day, in a daze from the shock and smoke and searing heat and at the request of a dying man caught in the explosion, a painting of a little bird, a goldfinch. The gentle beauty of this piece of art sustains you as you grow to manhood, serving as a sign that perhaps things are not as insignificant as they seem on the surface. But then the FBI is searching for the looted painting, and rumors emerge that it has surfaced in Europe, along with rumors that furniture sold at the shop has been sold under false pretenses. And all this time what’s really going on, though you wouldn’t have put it this way when you were thirteen, is that you are a young man on a journey of life in which death is only too real, as you yearn desperately for home, for a father, for significance, and for some hint that in the end life might offer more than loss.

If this sounds farfetched or implausible I assure you it will not be if you read Donna Tartt’s luminous and remarkable novel, The Goldfinch. I was drawn to Tartt’s novel because I love the painting—it actually exists—a small (3¼” x 9”) delicate oil by Carel Fabritius (1622-1654) done in the final year of his life. A contemporary of Rembrandt, Fabritius pictures the tiny bird chained to a perch, a creature designed to be free but kept from soaring. I had heard good things about Tartt’s earlier novels The Secret History (1998) and The Little Friend (2002), with people commenting that she published so few books because she worked on each one until every word was perfect. So I read The Goldfinch, delighted to have a copy in hardback—good books should have good bindings—and was captivated by Tartt’s prose by the time I had read five pages. It’s been a long time since I’ve read fiction as lovingly crafted, characters that came so alive as they developed, and a story that drew me in until I felt changed for having read it.

The story of Theo Decker in The Goldfinch is sometimes compared to Oliver Twist but though I believe both novels are masterful, and both are stories of marginalized orphans, I think this isn’t quite to the point. Dickens writes to expose the dark underbelly of capitalist London as a social critic whose conscience is finely tuned enough to protest against the rank pollution, the grinding child labor, and horrendous labor conditions of the working poor at the birth of modern industrialization. Tartt writes to bring us into the heart and life of an abandoned boy growing into manhood, forced to make his own way in a society where community is so fragmented that each individual must create their own identity, their significant relationships, and their own sense of meaning.

Now a man, walking through one more in an endless series of airports, Theo looks around and thinks about what he sees.

White noise, impersonal roar. Deadening incandescence of the boarding terminals. But even these soul-free, sealed-off places are drenched with meaning, spangled and thundering with it. Sky Mall. Portable stereo systems. Mirrored isles of Drambuie and Tanqueray and Chanel No. 5. I look at the blanked-out faces of the other passengers—hoisting their briefcases, their backpacks, shuffling to disembark—and I think of what Hobie [the antique restorer] said: beauty alters the grain of reality. And I keep thinking too of the more conventional wisdom: namely, that the pursuit of pure beauty is a trap, a fast track to bitterness and sorrow, that beauty has to be wedded to something more meaningful.

Only what is that thing? Why am I made the way I am? Why do I care about all the wrong things, and nothing at all for the right ones? Or, to tip it another way: how can I see so clearly that everything I love or care about is illusion, and yet—for me, anyway—all that’s worth living for lies in that charm?

A great sorrow, and one that I am only beginning to understand: we don’t get to choose our own hearts. We can’t make ourselves want what’s good for us or what’s good for other people. We don’t get to choose the people we are.

Because—isn’t it drilled into us constantly, from childhood on, an unquestioned platitude in the culture—? From William Blake to Lady Gaga, from Rousseau to Rumi to Tosca to Mister Rogers, it’s a curiously uniform message, accepted from high to low: when in doubt, what to do? How do we know what’s right for us? Every shrink, every career counselor, every Disney princess knows the answer: “Be yourself.” “Follow your heart.”

Only here’s what I really, really want someone to explain to me. What if one happens to be possessed of a heart that can’t be trusted—? (p. 760-761)

Dickens produced a classic cry for social justice in a society that grinds children under the heel of barons of wealth in a cold heartless world; Tartt has produced an exceptional meditation on whether beauty is a sign, a signal in a fragmented, heartless world that points to something beyond the trivial here and now, and whether in finding such a sign as we find ourselves we will find anything much at all.

I recommend The Goldfinch to you. Tartt writes such effortless, exquisite prose that it would be a shame to miss coming under the spell of her story. And there is too much in the story to process if we care about knowing our world and our own hearts.