“No More of This”

Pentecost Sunday, May 31, 2020.

5:30 pm. The House Between.

Margie and I did something we rarely do—we turned on the television news, WCCO to be exact, the local Minneapolis CBS affiliate. We usually prefer print sources for the news. The point isn’t print, it’s being discerning, but I’ll circle back to that later.

In any case, as I’m sure you know because the whole world knows, six days earlier, on Monday of Memorial Day weekend, May 25, 2020, George Floyd, a 46-year-old black man was murdered by a white Minneapolis police officer who pressed his knee onto Floyd’s neck for 8 minutes and 46 seconds as he lay on the ground in handcuffs. “I can’t breathe,” Floyd could be heard saying, as three other officers stood by without intervening.

The murder took place 17 miles, a mere 23 minutes drive from my front door.

Like so many around the world, I saw the videos and photos of George Floyd’s murder, sickened and horrified and enraged. The only word that is even close to being adequate to express all I thought and felt at that moment, and think and feel now is a profoundly biblical, deeply Christian word: Damn.

Say it aloud with me: Damn.

When you said it aloud, you were speaking truth.

This is not how those made in God’s image and bearing the dignity of his likeness are to be treated. Those who perpetuate such wickedness should beware: God is patient and forgiving but he will not be mocked. Even a casual reading of Scripture reveals that all those who love righteousness and justice, all who love God and neighbor must intentionally act to end such blatant evil, restore justice, bring healing and punish such casual killers.

Black lives matter

We have a “Black Lives Matter” sign in our front yard. I’ve heard white evangelicals object, saying that it should read “All Lives Matter.” This comment is usually intended to end the conversation, but it shouldn’t. Let me explain.

Certainly, all lives matter because all are made in God’s image, but that is not the subject we are considering. What is at stake here is not a review of the historically orthodox biblical doctrine of anthropology, but rather a reflection on what faithfulness looks like in this moment in America in the story of our lives. All lives matter but not all lives are equally vulnerable—and that is the issue we need to face. All lives will matter when black lives matter. Read again the classic parable Jesus told about the good Samaritan (Luke 10:25-37). The priest and Levite failed not because they never cared for anyone (Jesus never accused them of this) but because in contrast to their professed doctrine they refused to care for one specific, vulnerable, beaten and wounded man left to die in the street. Caring for him was costly in time, resources and effort but that is precisely what is required of a neighbor. And it is what is required of us. “Go and do likewise,” Jesus says, and in this moment in history in America that means we must say, sign and act on, Black Lives Matter. Refusing to care for black lives by deflecting the conversation into a consideration of the value of all lives is to join the priest and the Levite on their comfortable but depraved trip to Jericho.

In a post on his blog, New Copernican Conversations (May 31, 2020), my friend John Seel notes that it’s easy to be distracted from what should focus our attention and our concern:

The impulse is to blame “out of state, far left Antifa;” the impulse is to minimize the pattern and pervasiveness of police violence toward people of color; the impulse is to raise national concern only when buildings are burning rather than when Black lives are lynched. But even more, the fact that four cops can act in broad daylight with cameras rolling and citizens screaming in protest to their actions in such a murderous manner is all the proof that a normal citizen needs that something is terribly wrong with America. The fact that the police officer received the minimum charge after a four-day delay and that his accomplices have not been charged, raises questions that go beyond policing to the entire judicial system. The palpable outrage is understandable for there is a 400-year-old history and context to this behavior. All this has taken place in a progressive city with the entire nation watching. What about what happens in the dark, when the police body cams are turned off, in a less progressive city when no one else is around? The problems of American racism remain—perhaps less overt, but no less real or pervasive. Buried racism is still racism. Unconscious racism is still racism.

The fact that the charges against the officer who asphyxiated Floyd were subsequently increased and the other officers charged as accessories does not diminish Seel’s argument. Something is terribly wrong with America.

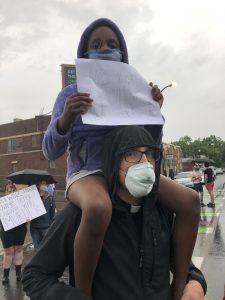

After Mr. Floyd’s murder, riots, looting and burning broke out across the Twin Cities and soon spread to other cities. Peaceful, nonviolent protests, with calls for justice and an end to racism—both systemic and individual—were organized, with hundreds, thousands of grieving and righteously angry citizens around the country and the world responding with chants and signs, masked because of the coronavirus pandemic.

I’ve heard white Americans, even Christians say that the riots, looting and burning delegitimize the protests. This too is often seen as a conversation stopper but shouldn’t be. It has the superficial trappings of an ethical argument but is a distraction not a compelling position, an excuse to ignore an unjust status quo. Again, let me explain.

Racism in America and violence against blacks are not new problems but a pernicious evil that stretches back to before our nation’s founding. The sad truth is that American society in general, and the Minnesota authorities more specifically have been unmoved by the killing of blacks by police. The killings have been going on for decades, while meaningful reform of the police and removal of barriers to justice have not occurred. Commissions have been appointed, hearings held, and reports issued, but substantial change has always been blocked. The question to ask is what should people do to catch the attention of authorities who not only withhold justice but are the ones doing the killing? Could it be that the only way to get the attention of authorities in a consumerist society is to raise a hand against business property?

The idea that the riots delegitimize the protest is predicated on the notion that burning buildings and looting businesses somehow relativizes seeking justice for murder. I can never agree as a Christian that looting trumps murder. I find that not only unethical, but morally repulsive. I am not arguing that rioting is admirable; I am arguing that to be incensed over the looting and burning without being more deeply angered and moved to sustained action for justice over the killing is an indefensible position ethically.

Jesus confronted this bankrupt moral reasoning in his day (Matthew 23:23-24):

Woe to you, scribes and Pharisees, hypocrites! For you tithe mint and dill and cumin and have neglected the weightier matters of the law: justice and mercy and faithfulness. These you ought to have done, without neglecting the others. You blind guides, straining out a gnat and swallowing a camel!

Besides, we must remember that the destruction of property has a long heritage in American history. I wonder if the white Americans making this spurious ethical claim realize that if true, then the Boston Tea Party delegitimizes the American Revolution and our nation’s subsequent independence. That day, December 16, 1773, colonists, angered at a tax imposed by the king, boarded ships at Griffin’s Wharf and dumped 342 chests of tea they had looted into the harbor. And by the way, when the story of America is told, these looters are not called “protesters” or “rioters” or “law-breakers;” they are usually called “patriots.” And they weren’t objecting to murder, mind you, but to a tax. Let that sink in: A. Tax.

No: the riots, the looting and the burning do not delegitimize the protests calling for justice. If anything, they should focus our minds and move our hearts so that we refuse to acquiesce to the status quo, but instead work for, and insist on change. Real, lasting change.

What else we saw

So, on that Sunday afternoon, six days after Mr. Floyd died, Margie and I watched on television as a massive, peaceful, chanting, sign-waving protest marched from Cup Foods, the place George Floyd was killed, to interstate 35W. It’s hard to know how many were involved, but the crowd filled the freeway—authorities later estimated 5-6,000 people. The interstate highways in the Twin Cities were to be closed that evening due to an 8 pm curfew. The closure was moved up to begin at 5 pm because of the protest.

Make no mistake: this was civil disobedience. Minnesotans know they should not march on an interstate. It was intentionally planned as a protest against racism and injustice, designed to get the attention of the authorities and the world, and call for change. Not a riot with looting, violence, destruction and burning, but a peaceful, nonviolent protest against racism and injustice. These were citizens exercising their First Amendment rights to demand justice. And a little before 5:30, in an act of civil disobedience, they moved off the city street and onto the freeway.

And then in a moment disaster struck and everything changed.

We watched on live TV as suddenly an 18-wheeler-tanker truck came barreling down the freeway directly into the crowd. People scattered, some falling as they tried to get out of the way, many leaping the barrier at the edge of 35W onto the grassy embankment and up into city streets. I can’t imagine how frightening it was to experience the encounter; just watching it was almost more than I could bear. Amazingly, thankfully, no one was hurt, except for the driver who was roughed up as he was pulled from the cab.

Busloads of officers arrived quickly and in force. They pushed through the crowd on the roadway, swinging sticks and spraying irritants, secured the truck driver and spirited him away. As they needed to do as officers of the law to ensure the driver’s safety, bound by a solemn oath to serve and protect.

Then the police quickly lined up forming a barricade across the highway (and though we couldn’t hear it), ordering the protesters off the interstate. Minnesota Governor Walz later said in a briefing that it had been determined that being on the roadway was unsafe and so the protesters had to be moved. Yes, it was unsafe, and the authorities were in a good position to know that—it was their job to close 35W to traffic. It was not a particularly difficult task, I must say, compared to all the complicated and coordinated deployments they needed to perform across Minneapolis and St. Paul since Mr. Floyd’s death, but they failed to accomplish the closure adequately.

The lines of officers ordered the protesters off and then moved forward, firing tear gas and projectiles into the crowd to make them move. Most moved, many stumbling blinded up the ramp and onto the city street.

Two men, however, stood their ground on the freeway. They simply stood, unmoving, in the middle of the interstate. A group of officers approached them, and (I assume) repeatedly ordered them to move. The two men remained still. As the officers approached, the two lifted their hands in the air and prepared to be arrested. They offered no resistance. It’s called civil disobedience. Because of conscience, a law is broken to make a case for some higher principle, and then the consequence of the lawbreaking is accepted.

The officers approaching them were backed up by dozens of their comrades so if the two men had decided to resist or become violent, they would have been easily overwhelmed and restrained. It was an unmistakable case of overwhelming force. The officers approached the two men—citizens, neighbors—arrested them and placed them in handcuffs.

A cruel, unnecessary act

But first, at point blank range, standing right in front of the two peaceful, unresisting citizens, the officers sprayed chemical irritant directly into their faces. I was horrified, and then disgusted and very angry.

It was a cruel, unnecessary act.

There is a lot about this incident I do not know and will happily admit that I don’t know. There was no sound from the scene as we watched (except for comments by reporters) so I don’t know if the officer’s verbal orders to move off the interstate were clear. I assume they were, but even if they weren’t the officer’s actions and movements clearly indicated the same message. I also don’t know what the irritant was, mace or pepper spray; but it doesn’t matter. Either way I know this: it was a profoundly cruel, utterly unnecessary act.

We weep, O Lord,

for those things that,

though nameless, are still lost.

We weep for the cost of our rebellions,

for the mocking and hollowing of holy things,

for the inward curve of our souls,

for the evidences of death

infecting all fabrics of life.

[From Every Moment Holy]

I do not know whether this is standard Minneapolis Police Department policy. Perhaps the official procedure for arresting nonviolent, peaceful protesters engaging in civil disobedience includes spraying irritant directly into their faces. If it is then the policy must be revoked, and the police retrained. It is a cruel, unnecessary act.

I also cannot imagine the apprehension and fear the officers must have felt to be deployed in such a situation on an interstate. Especially after nights of riots with looting, violence and burning in various neighborhoods throughout the city, and beyond. Especially after authorities found hidden caches of flammable liquids in empty lots near businesses not yet torched. Especially after state troopers stopped cars without license plates, whose occupants scattered, to find inside tools used to break into buildings. I cannot imagine it, and I salute the officers who put themselves in harm’s way for the common good and public order. On Sunday, on 35W, the arresting officers stood opposite the two men for some time before moving towards them. They were backed up by dozens of other officers, and as they stood in the middle of the interstate more officers arrived and deployed near them. This was not a quick encounter where snap judgments needed to be made. As the officers moved towards the protesters, the two men signaled their submission by placing their hands in the air and turning their backs to the officers, so the police were totally in control. And still, instead of simply handcuffing the two men, the officers sprayed irritant directly into their faces. Still, they offered no resistance. It was a cruel, unnecessary act.

The fact that these officers could do such a thing without trying to hide it, in full view of cameras that would not only record their behavior but send videos around the world is a chilling realization. I have to assume they believed this was fully within their purview as officers of the law. How could such wickedness—a murder and now this—occur on the streets of my city?

I write this last sentence, noting my surprise at events and realize that I need to hear and receive the loving rebuke of my sister, Courtney Ariel. In “For Our White Friends Desiring to Be Allies” in Sojourners (8/16/17) Ariel speaks these words to me:

Please try not to, “I can’t believe that something like this would happen in this day and age!” your way into being an ally when atrocities like the events in Charleston, SC, and Charlottesville, VA, happen. People of color have been aware of this kind of hatred and violence in America for centuries, and it belittles our experience for you to show up 300 years late to the oppression-party suddenly caring about the world. Don’t get me wrong, I welcome you. I want for you to come into a place of awareness. However, your shock and outrage at the existence of racism in America echoes the fact that you have lived an entire life with the luxury of indifference about the lives of marginalized / disenfranchised folks.

I hear you.

As I watched the confrontation on 35W, I was reminded of tragically similar images from the famous march in 1965 led by Martin Luther King, Jr., on the highway outside Selma, Alabama. Apparently, when it comes to racism and police brutality, we’ve made little or no progress. And if we have made progress, I insist it is horribly insufficient. What the police officers did in 1965 and in 2020—to name only two times out of so many—were cruel, unnecessary acts.

I understand that one model for effective urban policing is militarization. Equipment, including armored vehicles and weaponry from the United States Armed Forces has gone to police units across America and training in military tactics has been encouraged. Some leaders have even called for the deployment of the military, responding not to the brutal killing of a black man but to the torching of places of business. Is this truly the best way to serve and protect?

Years ago, during the 3+ decades we lived in Rochester, MN, our neighborhood saw a wave of crime. A slumlord bought up houses and rented out individual rooms without care for either the properties or the character of his tenants. Drug trafficking became extensive, several of the landlord’s properties became crack houses, and violence followed. A shooting occurred outside our home. The neighborhood appealed to the City Council and the police department responded. Instead of arriving like a military force moving in to occupy and pacify the neighborhood, they sent a single cop. A single, neighborhood cop.

I remember at the time an old joke about the fabled Texas Rangers made the rounds. Apparently, the sheriff of a small town appealed to the Rangers because a riot had broken out. The sheriff waited for the afternoon train from which a single Ranger emerged. “There’s only one of you?” the sheriff asked incredulously. “Well,” the Ranger drawled, “There’s only one riot, isn’t there?”

Anyway, every day our neighborhood cop parked his squad car prominently on the street. He walked his beat of about 6 square blocks, meeting all the neighbors, responding to complaints, and making arrests when that was appropriate. He knew our names and where we lived, interacted with our children and gained our trust. The violence receded, the drug dealers were arrested or moved on, the slumlord was convicted and sent to prison, and everyone in the neighborhood held the police in higher regard. He defused volatile situations, told us how we could help, warned us what not to do, and brought a calming presence to the neighborhood. Never once did he engage in a cruel and unnecessary act.

It’s significant that what’s been occurring prompted General James Mattis to break his silence and speak out publicly in The Atlantic (June 3, 2020):

When I joined the military, some 50 years ago, I swore an oath to support and defend the Constitution. Never did I dream that troops taking that same oath would be ordered under any circumstance to violate the Constitutional rights of their fellow citizens—much less to provide a bizarre photo op for the elected commander-in-chief, with military leadership standing alongside.

We must reject any thinking of our cities as a “battlespace” that our uniformed military is called upon to “dominate.” At home, we should use our military only when requested to do so, on very rare occasions, by state governors. Militarizing our response, as we witnessed in Washington, D.C., sets up a conflict—a false conflict— between the military and civilian society. It erodes the moral ground that ensures a trusted bond between men and women in uniform and the society they are sworn to protect, and of which they themselves are a part. Keeping public order rests with civilian state and local leaders who best understand their communities and are answerable to them.

James Madison wrote in Federalist 14 that “America united with a handful of troops, or without a single soldier, exhibits a more forbidding posture to foreign ambition than America disunited, with a hundred thousand veterans ready for combat.” We do not need to militarize our response to protests. We need to unite around a common purpose. And it starts by guaranteeing that all of us are equal before the law.

As a Christian I believe in civil disobedience. I believe in it because my faith requires of me total and final allegiance to Jesus as Lord. This is why when the high priest’s council ordered St. Peter and the other apostles not to speak of Christ, they refused to obey. “We must obey God rather than any human authority,” they said, and proceeded to act accordingly (Acts 5:29). As a Christian I must never be dismissive of the laws of the land and must not be known as lawless. But I serve a higher authority and my primary citizenship is in the kingdom of God. The Lord I serve is the God of justice and righteousness and so my concern must be for justice and righteousness as well. “He has told you, O mortal,” the prophet Micah said, “what is good; and what the Lord requires of you but to do justice, and to love kindness, and to walk humbly with your God” (6:8). I believe in civil disobedience because it has a long and noble heritage in the history of Christ’s Church. Now, having watched the confrontation on the bridge on 35W, I realize that if in trying to be faithful to my Lord and his gospel I am led to an act of civil disobedience in my home state of Minnesota, I will not merely be arrested, but will first be intentionally hurt by the arresting officers. Perhaps it won’t happen because I am white. I don’t remember whether the two men were black. Certainly, some in the crowd were white that were sprayed with irritants and shot with projectiles to move them off the highway. So, it is best that I expect to be subjected, before being placed in handcuffs, to a cruel, unnecessary act. And when that happens, I will remember that my black sisters and brothers have suffered such cruel, unnecessary acts for a very long time.

The story of America that I hear from white Americans is that police brutality is a problem in other places, in foreign lands. That intentionally hurting, spraying irritants directly into the faces of compliant, nonviolent citizens protesting injustice—that such outrages occur not in America but under authoritarian regimes in places like North Korea, China, Russia, Syria, Saudi Arabia and under the Taliban in Afghanistan. The story says such brutality is actually forbidden in America, and if someone being arrested in America is hurt in the process it is their own fault. Yet, here it is in progressive, nice Minnesota, an unnecessary and cruel act perpetrated by the Minneapolis police.

Minnesota Nice, Minnesota Paradox

I have deep roots in Minnesota. I love living here.

My great-grandfather Haack owned a grocery store in Stewartville, MN, 90 miles from where I am sitting. Each year he would commission a special piece of pottery from the Red Wing Pottery Company to give to his best customers. On each piece would be stenciled, “Haack’s Store, Stewartville, MN.” Now they are rare and sought by collectors. His son, my grandfather Haack was mayor of Stewartville briefly and over the years owned a farm just outside town and then a construction company. I also married a woman who was born and raised in Minnesota.

Both Margie and I have been shaped by the culture here, have lived here for decades, and love the vastness of the prairies, the expanse of lakes and the wildness of the woodlands and bogs that house such a rich variety of flora and fauna. Our spirituality has been molded by the flat, wide open, rich landscape of farmland, lakes, rivers, wet-lands, and woods that stretch to the far horizon. We love the clear, four seasons, and the glorious changes of color that characterize each one. We love the massive migrations of waterfowl that fill the sky twice a year, and the rich black soil that provides food for so many.

And we like Minnesota Nice. That’s the expression commonly used to describe what it is like here: people tend to be nice, the sort of state that could give rise to the “News from Lake Wobegon, where all the women are strong, the men are good looking and the children are above average.”

What is far less pleasant, so much less pleasant that it is kept hidden and seldom if ever acknowledged is something identified by Samuel L. Meyers, Jr., an economist at the University of Minnesota. He called it the Minnesota Paradox. “That is,” Paul Mattessich, Executive Director of Wilder Research reports in MN Compass (March 2015), “despite the high quality of life for our population overall, specific groups of residents in our state fare poorly on social and economic measures, and the disparities among racial groups stand among the worst in the nation.”

The Minneapolis Star Tribune reports Dr. Myers’ research reveals that “the large gap is largely due to special benefits made available over time to the white population that’s led to substantially higher wealth than blacks. And he argues that wealth results from the favored treatment whites have long received from banks in making loans.” David Leonhardt reports in the New York Times (6/1/2020), “Incomes for white families [in Minneapolis and St Paul] are similar to those in other affluent metro areas, like Atlanta and Los Angeles. Incomes for black families are close to those in poorer regions like Cleveland and New Orleans.” City planners developed large infrastructure projects to go through black neighborhoods rather than white ones. The resulting highways disrupted community life, forced the closure of minority-owned businesses and forced families from their homes. Home ownership rates were lower in these neighborhoods, and the disruption from the infrastructure projects only added to the problem. Authorities could claim they were being sensitive to citizen input only because blacks had no voice, no power and no wealth.

In January of this year, Greg Miller described in City Lab (www.citylab.com) some of what transpired in the Twin Cities to bring this disparity into being:

Before it was torn apart by freeway construction in the middle of the 20th century, the Near North neighborhood in Minneapolis was home to the city’s largest concentration of African American families. That wasn’t by accident: As far back as the early 1900s, racially restrictive covenants on property deeds prevented African Americans and other minorities from buying homes in many other areas throughout the city.

In 1948, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that such racial covenants were unenforceable. But the mark they made on America’s neighborhoods lived on: By excluding minorities from certain parts of a city and concentrating them elsewhere, these racist property clauses established enduring patterns. They were reinforced by redlining, a discriminatory home lending practice promulgated by real estate agents and federal housing programs in the 1930s; later, urban planning decisions on highways and other infrastructure projects followed the lines inscribed by decades-old covenants.

The effects still reverberate today: Despite its reputation for prosperity and progressive politics, Minneapolis now has the lowest rate of homeownership among African American households of any U.S. city.

The fact that the Minnesota Paradox is kept intentionally out of sight means it is also kept out of mind, and so meaningful progress, reform and resolution isn’t permitted to occur. Being nice, it turns out, can hide a multitude of evils, allowing them space to fester and infect the entire society. It’s true the Minnesota Paradox is a horribly complex, difficult problem that will take considerable effort and significant resources to begin to unravel. That’s not a reason to keep it hidden, but simply what we should expect when wicked patterns of behavior, perverse prejudices and broken societal structures are allowed to become normative. Every aspect of society in Minnesota will need to be addressed and no doubt all sorts of vested interests will have reasons to keep the change from occurring.

It’s time for Minnesota Christians, and all those who love virtue and justice, to stop being so damned nice. Things need to change.

White privilege

I am the recipient of white privilege. I am privileged to learn about racism from books, articles and television rather than experiencing it as black Americans do. I am privileged to study late on campus at Covenant Theological Seminary in St Louis, or to teach an evening class (I’ve done both) and later that night drive through the prosperous white neighborhood surrounding the campus and not fear being pulled over as black students regularly are, to have a police officer demand, “What are you doing in this neighborhood?” I am privileged to be able to buy property in the Twin Cities without certain areas cut off from me due to redlining. I am the recipient of white privilege when I do not fear going to court and being treated unfairly due to my race.

If you doubt the reality of white privilege in America—and amazingly some people do—review the reports, photos and videos from recent protests in Wisconsin when white men armed with loaded assault rifles demanded the governor allow businesses and bars to reopen. Calling the medical stay at home orders at the height of the coronavirus pandemic part of a “Communist” takeover, these protesters carried their weapons openly in public, without fearing arrest or even a serious challenge from police. White privilege in public view, on steroids.

A couple of years ago I attended a diocesan conference in Wheaten, IL. One workshop was led by a young black man pastoring a congregation in Chicago. He told of how he had been pulled over by police only to discover he had forgotten to place proof of insurance in his car after paying the latest premium. The officer issued a citation and he was required to appear in traffic court. The day in court went by with boring regularity, he said. A name was called, a person would identify themselves, the judge would ask if they had proof of insurance the day they had been issued the citation and upon hearing, “No,” the judge would issue a fine, and the bailiff would call the next name. For the first couple of hours, the pastor told us, each name identified a black person. “Did you have insurance?” “No.” The fine was imposed. “Next.” Each case only required a few minutes. Then, the pastor said, a name was called, and a white man stood up. “Did you have insurance?” “No.” “Can’t we do something to help this young man?” the judge asked the district attorney. “It’s not good to have this on his record.” “You can dismiss the charge,” the DA replied. “Dismissed,” the judge said. “Next.” A black person stepped forward, and a fine was issued. Thus, it went through the day, the young pastor said. He said he wished he hadn’t proof of insurance so he could request to be treated as the whites were being treated but admitted it may have only increased his fine.

I would not have had a fine in that traffic court, even if I hadn’t had proof of insurance. It’s called white privilege and American society is rotten with it.

Whites who deny the existence of white privilege need to open their eyes and ears to the truth. How many of us whites would be happy to be treated the way blacks are treated today in Minnesota, in America? Luke Bobo has told me how black fathers are careful to teach their sons how to act and respond when they are pulled over by a cop while driving. To make a mistake, even a small one at such a moment is to court disaster. I never thought of doing that with my son, and never heard it was a concern among white fathers.

Racism in my beloved state goes back a long, long way. In 1849, President Zachary Taylor appointed a Pennsylvanian, Alexander Ramsey, as Governor of the Minnesota Territory. White settlers were anxious to have access to lands west of the Mississippi River, and Ramsey saw that the only way to accomplish that was to forcibly remove the Native Americans who owned that land and had lived there for decades. So, on September 9, 1862, Governor Ramsey addressed the Minnesota Legislature in special session. “Our course then is plain,” Ramsey said. “The Sioux Indians of Minnesota must be exterminated or driven forever beyond the borders of Minnesota.” A year later Congress passed laws forcing not only the Dakota but also the Ho-Chunk from the state.

The ripple effects of this injustice remain with us to this day. If such things happened in another land, we’d call it genocide, ethnic cleansing. And we’d be correct.

In the Harvard Gazette (December 2017), Bryan Stevenson calls us to open our eyes to the truth, no matter how painful:

It’s critical at this moment in our nation’s history that we talk about race. Slavery didn’t end in 1865. It just evolved. It turned into decades of terrorism, violence, and lynching. And the era of lynching was devastating. It created a shadow all over this country, and we haven’t talked about it; we haven’t confronted it.

“The true evil of American slavery wasn’t involuntary servitude,” he said. “It was the narrative of racial difference, the ideology of white supremacy that we made up to justify slavery. That’s the true evil.”

“Black people were kidnapped, taken out of their homes,” said Stevenson. “They were murdered. They were beaten. They were hanged. They were brutalized. They were terrorized, and they have never been recognized. And in the 20th century, we created one of the largest mass migrations the world had ever seen. Millions of blacks fled the American South. The black people who went to Cleveland, Chicago, Detroit, Los Angeles, or Boston didn’t come to these communities as immigrants looking for economic opportunities. They came as refugees and exiles of terror from the American South.”

The reticence to face the truth of these things goes back, I think, at least partly to the fact we take pride in believing that America is the finest country in the world. It is a “city on a hill,” demonstrating what freedom and a free market can provide in a world full of oppression, tyranny and grinding poverty. None of us wants to end up in court accused of some wrongdoing, but if we are, we want it to be an American court that houses the fairest system of justice in the world. We take pride in the symbolism of the Statue of Liberty and believe that it captures our nation’s spirit and core beliefs. The idea that we have done and are doing wrong, that justice is systematically withheld from a significant portion of our fellow citizens and that as a nation our guilt for genocide, slavery and racism threatens to undo us seems too much to bear. It’s why some even put forward the preposterous and divisive claim that those who talk about problems in America actually hate America.

This is the same understandable but mistaken impulse that causes members of my tribe to produce sentimental religious art. Paintings full of nostalgia for a lost, pristine world where little houses shine with warm light amidst gardens bursting with flowers. Fiction where people doing bad things never use bad language, where challenges to faith are easily resolved and where most everyone is saved before the final page. Where biographies of heroes of the faith, missionaries and martyrs, are really just idealized, adulatory hagiographies. Music of dubious theological merit and simplistic composition. All this is understandable, as I say, but as a careful reading of Scripture demonstrates, badly mistaken.

Scripture tells stories peopled by both villains and heroes, and all the heroes are sinners. The world is broken and at no point are we allowed to look away so as to miss the brokenness. Many biblical texts seem specifically designed to rub our noses in the problem. And if we miss the point as we read various narratives, the prophets will set us right. The prophets also remind us that we need not fear being realistic about the fallenness because we have been granted grace. Grace allows—no, insists—we see sin in all its horror because only then are we prepared to receive the hope of redemption. Christ’s resurrection only makes sense when we look unflinchingly at the bloody torture, injustice and painful horror of Christ’s cross.

Loving America means I will insist that it honors its deepest commitments, including that “all men [and women] are created equal.” And where it fails to do so, love requires me to not remain silent or to tell a story of America that lies by ignoring that bit, but to work for justice, speak truth to power and insist changes be made.

Mass incarceration

And that brings us to mass incarceration, a topic that’s difficult to discuss because it is so politicized and surrounded by so many myths. Bryan Stevenson, in The New York Times Magazine (August 14, 2019), insists that its roots are in slavery.

The United States has the highest rate of incarceration of any nation on Earth: We represent 4 percent of the planet’s population but 22 percent of it’s imprisoned. In the early 1970s, our prisons held fewer than 300,000 people; since then, that number has grown to more than 2.2 million, with 4.5 million more on probation or parole. Because of mandatory sentencing and “three strikes” laws, I’ve found myself representing clients sentenced to life without parole for stealing a bicycle or for simple possession of marijuana. And central to understanding this practice of mass incarceration and excessive punishment is the legacy of slavery.

Making the case for this is beyond the scope of this essay and is better made by others with expertise I do not possess. Read their work. My challenge to white Christians in America is not that you take my word for it, but that you be faithful to your convictions and search out the truth.

Begin with a few facts. Research indicates that African Americans and whites use drugs at similar rates, but the imprisonment rate of African Americans for drug charges is almost 6 times that of whites. African Americans represent 12.5% of illicit drug users, but 29% of those arrested for drug offenses and 33% of those incarcerated in state facilities for drug offenses. And here is where a widely believed myth arises. Michelle Alexander argues in The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness, we need to reexamine our assumptions.

Most people assume the War on Drugs was launched in response to the crisis caused by crack cocaine in inner-city neighborhoods. This view holds that the racial disparities in drug convictions and sentences, as well as the rapid explosion of the prison population, reflect nothing more than the government’s zealous—but benign—efforts to address rampant drug crime in poor minority neighborhoods. This view, while understandable, given the sensational media coverage of crack in the 1980s and 1990s, is simply wrong.

And then examine how mass incarceration functions similarly to Jim Crow. Alexander, again:

…mass incarceration is a system that locks people not only behind actual bars in actual prisons, but also behind virtual bars and virtual walls—walls that are invisible to the naked eye but function nearly as effectively as Jim Crow laws once did at locking people of color into a permanent second-class citizenship. The term mass incarceration refers not only to the criminal justice system but also to the larger web of laws, rules, policies, and customs that control those labeled criminals both in and out of prison. Once released, former prisoners enter a hidden underworld of legalized discrimination and permanent social exclusion. They are members of America’s new undercaste.

This is not a partisan issue, nor a political one. It is an issue of morality and justice. Christians need to push back against every attempt to politicize the discussion and insist that mass incarceration be examined thoughtfully. We may not agree at the end exactly what should be done but if we aren’t courageous enough to do the hard work of thinking it through, we will fail to be faithful to what we believe to be true in Christ.

Conspiracies, so many conspiracies

To make matters worse, conspiracy theories—multiplied in impact many times over by social media—are infecting our society with disinformation, lies, unsubstantiated accusations, partial truths, distrust, fear and dangerous falsehoods.

They are legion: The existence of a Deep State. Birtherism. QAnon. Secular medical authorities ordering churches closed during the pandemic are anti-religious and anti-Christian. Mainstream press is the enemy of the people. The idea of systemic injustice is a fiction promulgated by liberal theologians as part of the social gospel movement. Vaccinations cause autism. Bill Gates is behind a global vaccination plot and an effort to embed microchips in children. Coronavirus is of Chinese manufacture, released from a Chinese lab. George Soros is financing the protests and riots.

I said at the beginning of this piece that Margie and I rarely watch television news. It’s because we want to be discerning. Print allows us to consume the news at our own pace, while television forces us into the pace set by the broadcasters. It allows us to pause and reflect as we read, a necessary component in the process of discernment. Reading allows us to stop and check sources, seek further information, look up definitions (“performative allyship” for example), research background, and provides a chance to step back periodically so we don’t lose the forest for the trees. Print sources for the news also frees us from being manipulated by the emotional tone set by television. I realize print can transmit emotion, but the difference in impact is indisputable. Some broadcasters, outlets and commentators are popular today because they speak in forceful, excited tones of outrage, spreading that outrage to their viewers. However, just because something is exclaimed repeatedly in ways designed to inflame doesn’t make it true, edifying or helpful. In fact, the heightened tone makes it more difficult to analyze the content critically making it more likely it’ll simply be accepted as gospel. I’ve been in Christian’s homes where this sort of hyped TV commentary remains on in the background for long hours—hardly a good way to deepen the fruit of the Spirit in our lives. As James K. A. Smith observes in Image (Winter 2018):

If I’ve learned anything from Saint Augustine, it is an eyes-wide-open realism about our tendency to ruin things. And so, unsurprisingly, even our distractions have been hijacked by the worst angels of our nature. Now we turn to these devices over and over again looking for that peculiar joy of late modernity: the joy of outrage. The delight we take in recognizing what is detestable. The twisted bliss of offense. The haughty thrill of being aghast at the latest transgression. We can’t believe he said that, and we secretly can’t wait for it to happen again. Like love’s negative, the joy of outrage is expansive: it only grows when it is shared.

Still, the primary point I am making here is not print versus television and social media, but the need to be discerning. We need to be skilled in tracing the subtle impact of ideological or political bias. All sources are biased because every human being is biased. There are no exceptions. Everyone has some sort of world and life view, and that perspective shapes what we hear and see and how we report it. A discerning Christian will not try to find an unbiased source of news, because that does not exist. Nor will we try to find one whose bias we like or agree with so we can relax and simply absorb what they report. That will result in being less motivated to be discerning, a sure recipe for sliding into ever greater unfaithfulness. Listening carefully to the very best thinking from a variety of perspectives, ideologies, political agendas and worldviews permits us to better discern misperceptions, partial truths, opinions and emotional tone. Tim Keller has it exactly right in dailykeller (July 9, 2019):

Many of us listen only to people of our own race or class or political persuasion and not to others. Wisdom is to see things through as many other eyes as possible, through the Word of God and through the eyes of your friends, of people from other races, classes, and political viewpoints, and of your critics.

Disagreement need not be divisive; distrust always is. As a Christian I must always be eager to humbly listen to and learn from those who think I am wrong; as a Christian I am never permitted to dismiss them as my enemy or to shut my ears to what they say.

We need to be strict with ourselves to check sources carefully and never share anything if we haven’t read the entire piece and verified its veracity. The internet is a wonderful tool but the ease it provides us in passing along material can prove disastrous if we are not careful to be discerning in what we forward on to friends.

Obviously, television has one obvious and very wonderful advantage: it’s able to report and stream live events as they unfold in real time. We’ve had the television news on a lot recently.

Social media also has its important place in modern life. Many voices—of minorities, activists, people outside the world of journalism, community leaders, ordinary neighbors—will never be heard in print. Reading their blogs and posts and listening to their podcasts can be an important way to learn, be informed and challenged. But with this as well, let’s be discerning.

Conspiracy thinking is not a new problem. As human beings in a broken world, we are finite, and we are fallen. We live in a world where negative forces disrupt our plans and take society in directions that we believe are unfortunate and perhaps even dangerous. It’s enough to make any right-minded person a bit afraid. What’s going on? Are they going to take over? The negative forces seem too powerful and widespread to be coincidental or the work of a few disparate individuals. We see that like-minded people network, and meet together, which becomes proof that it is an organized effort of subversion. We assume there is some sort of coordination behind the scenes, some conspiracy that is underway by groups and people that intentionally stay hidden while spreading their toxic influence to change society in nefarious ways.

The primary motivation in this is fear. We latch onto conspiracy theories because we fear what is going on around us, fear the direction everything is headed, fear that going down this road is misguided if not deadly, and fear what will happen to us, to our families, our future and all we hold most dear. Naming a conspiracy doesn’t erase our fear, of course, but it helps us feel better, just like having a diagnosis for our condition is better than simply being sick all the time. We have identified the forces aligned against us, we can begin to isolate ourselves from their influence and we can name the conspirators as the enemy.

For the Christian, the primary solution is not to stop fearing but to fear the right thing instead. We have no reason to fear anything in this world; we have every reason to fear the Lord.

So, beloved of God, hear the word of the Lord spoken through Isaiah:

For the Lord spoke thus to me with his strong hand upon me, and warned me not to walk in the way of this people, saying: “Do not call conspiracy all that this people calls conspiracy, and do not fear what they fear, nor be in dread. But the Lord of hosts, him you shall regard as holy. Let him be your fear, and let him be your dread. And he will become a sanctuary.” (8:11-14)

Fearing the world is sin for me; fearing the Lord is the beginning of wisdom.

The popularity of modern conspiracy theories is of great significance to the Church for the simple reason that truth is central to our faith. Our Lord did not merely insist that truth was important to him, he identified himself as the truth. We need to stand against conspiracy mongering by insisting on the truth and fearing only the Lord.

Just because we find connections between people and institutions does not make it a conspiracy. All like-minded people—conservatives, progressives, educators, engineers, dentists and Christians—network, organize conferences, work together and seek to increase the impact of their programs and concerns. “Showing connections between people and groups is one thing,” Douglas Groothuis warns in Unmasking the New Age, “showing conspiracy is another.”

The conspiracies circulating and poisoning minds and imaginations today spread and mutate quickly, weaponized by social media. Often, they are spread by unsuspecting folk, since they heard it from a friend or leader or so-called expert and so assume it must be true. It often isn’t. Read and listen widely, read and listen wisely, read and listen with discernment.

Racism

Racism is a great evil. It is an affront to the person who is made in the image of God, and it is an affront to the God whose image we bear as human beings. The first affront is a sin that should fill us with lament and repentance; the second should fill us with terror.

Terror: not an acceptable word today when speaking of God.

Sometimes I hear someone say they don’t like Christianity because the God of Scripture is described as a Judge, a God of wrath. They prefer a benevolent deity. It sounds nice (there’s that word again!), but I would argue there is a catch. Let me explain:

When Native Americans were forced from their homes by soldiers and slaughtered—the aged and infirm, infants, children, women as well as armed combatants—I want a God who hears their cries and declares, “This will not stand!” When blacks were kidnapped from their homes in Africa, herded like cattle and loaded onto crowded, stinking, unsanitary, disease-ridden slave ships, sold and mistreated by white owners, I want a God who is righteously angry enough to proclaim, “This will not stand!” When nice, white Minnesotans refuse to do the hard work of societal reform to uncover and tear down hidden barriers that keep people of color from being able to flourish economically, and to stamp out police brutality and judicial unfairness, I want a God who will insist, “This will not stand!” I do not want a tolerant, benevolent deity that will smile at such tragedies. I want a God who will pour out his wrath on all such injustice, and in judging it not just stop it, but undo it, utterly and forever, so that heaven works backwards until all is made right, so that righteousness fills the earth as the waters cover the sea. So that in the end everything is redeemed, so that every instance of suffering is made better than it could have ever been if it hadn’t occurred at all, its significance known, and its purpose glorified. The God of Scripture is the I AM, meaning that every moment in time is equally present for him, so his judgment is not after the fact and remedial, but in the moment and fully redemptive. This is his world; he has not abandoned it and he will do what is right. And it is because I worship a God of wrath that I must not remain silent in the face of injustice. And why has he not instituted his final judgement? I do not know except perhaps to give us time to repent and work for justice.

Diversity is a gift of God’s grace. This is simply axiomatic for the Christian. The picture of the new heavens and earth given in St. John’s Revelation is one where the people of God from every tribe, every people, every culture, every language together serve, worship and hymn their Lord and Redeemer. This is not a picture of homogeneity but of rich diversity to God’s glory, world without end. And it certainly is not an image of white cultural supremacy.

I hear some white Americans argue at this point that they prefer to look forward, not backwards. That rehearsing mistakes in the past is counterproductive, when we should be concentrating on future progress. Besides, we didn’t personally own slaves or insist a black can’t move in next door or kneel on a man’s neck for 8 minutes and 46 seconds. I’m not certain in what worldview this argument against looking back would appear coherent. The Christian faith insists precisely the opposite: that it is impossible to flourish as human beings without honest, true confession and repentance. If we are unwilling to look back and honestly confess, there is no possibility of redemption. Though I have stated this using distinctly religious terminology, secular psychologists have come to the same conclusion.

Bruce Springsteen, in Rolling Stone (June 3, 2020) recognizes we are burdened by the sins in our past.

We remain haunted, generation after generation, by our original sin of slavery. It remains the great unresolved issue of American society. The weight of its baggage gets heavier with each passing generation.

If we refuse to honestly face and name our difficulties and shortcomings, our wickedness and sins, we will be unable to move past them into healing. We must see and confess we have been wrong, repent and determine to change, and then do all that is necessary for reform, make amends and seek reconciliation and healing. It’s the reason my Church tradition insists on an unhurried period of Confession and Absolution each and every Sunday as we meet for worship around the Word and Sacrament. My only complaint about it is that for me, at least, weekly is not anywhere near sufficient.

The ancient Hebrew prophet Isaiah spoke the word of God to God’s people. It’s a word we need to hear and believe and live in. Isaiah 58 is long, but I suspect that’s the point—we fallen mortals tend to be hard of hearing. I’ll only quote part of it here, but please take the time to read it. Read it slowly, prayerfully. It’s a word we white American Christians need to hear.

Cry aloud; do not hold back;

lift up your voice like a trumpet;

declare to my people their transgression,

to the house of Jacob their sins.

Yet they seek me daily

and delight to know my ways…

‘Why have we humbled ourselves,

and you take no knowledge of it?’

Behold, in the day of your fast you seek your own pleasure,

and oppress all your workers…

Fasting like yours this day

will not make your voice to be heard on high…

Is not this the fast that I choose:

to loose the bonds of wickedness,

to undo the straps of the yoke,

to let the oppressed go free,

and to break every yoke?

Is it not to share your bread with the hungry

and bring the homeless poor into your house;

when you see the naked, to cover him,

and not to hide yourself from your own flesh?

Then shall your light break forth like the dawn,

and your healing shall spring up speedily;

your righteousness shall go before you;

the glory of the Lord shall be your rear guard.

Then you shall call, and the Lord will answer;

you shall cry, and he will say, ‘Here I am.’

So, what do we do?

The audience I am speaking to in this essay is my tribe: white American Christians. If the question is what should be done to change society, I must take a step back. I’m a learner at this point, not the teacher; a follower, not the leader. Thankfully, there have been plenty of articles and books published by black activists, scholars, novelists, thinkers and community leaders—read and learn from them. What I am willing to do is make some suggestions about what faithfulness might look like for white American Christians.

More specifically, I can tell you a few of the things we have chosen to do. Please see this not as some formula anyone else should replicate but merely as our feeble attempt to be faithful as followers of the Lord Christ. So, here is a brief glimpse of some of what we’re doing:

We have gone back to Scripture. This is always the first step we take when we need to reconsider the shape of our faithfulness in a broken world. Each of the stanzas in the biblical story, Creation, Fall, Redemption and Restoration speaks directly to the questions of race, the dignity and value of persons, and social justice. It’s been good to pray through together what is being said, what it means and how we should flesh it out in our lives. In the process, we have been reminded of the strong words of warning spoken by God in his word to his people:

Rescue those who are being taken away to death; hold back those who are stumbling to the slaughter. If you say, “Behold, we did not know this,” does not he who weighs the heart perceive it? Does not he who keeps watch over your soul know it, and will he not repay man according to his work? (Proverbs 24:11-12)

That return to our foundations has steeled our determination to do something and be involved in the pursuit of justice and the reform of society. My reading of Scripture simply leaves me no alternative. Edmund Burke was correct when he asserted, “The only thing necessary for the triumph of evil is for good men [and women] to do nothing.” Racism, police brutality and justice will help determine our vote, and we will contact governmental and community leaders to insist on change and recommend supporting appropriate legislation and reform.

We have placed a sign in our yard and are arranging one to be placed on our car. It’s true that our house is on a quiet cul-de-sac 17 miles from Cup Foods, the place George Floyd was murdered, and that because of the pandemic our car is usually in our garage. So, these are small ordinary things, but still we will do them. And we will keep at it instead of being concerned only when some crisis occurs.

A couple of years ago we added Bryan Stevenson’s Equal Justice Initiative (www.eji.org) to the list of organizations we support financially. We wish we could donate more, and it will certainly not be less.

We will seek to remain, by God’s grace, people of hope. We cannot give in to despair because to do so would call into question the possibility of redemption. “It does feel a tipping point from the blindness of white privilege / power is happening,” a friend emailed after attending a peaceful protest for George Floyd in Minneapolis. “I hope voices can emerge that can help tip towards love over against power on the far side of it all. I can’t feel too optimistic right now though; so much hurt and anger and (on the other side) stiff-necked pride of power. A president who believes this is a power struggle and is determined to ‘win’ is not going to help!” Our Lord remains committed to his world, and so we will as well.

We will speak truth to and in the white church. We will continue to recommend our fellow believers read books specifically written for them that explore the issue. Such as Erskine Clarke’s superb, By the Rivers of Water: A Nineteenth Century Atlantic Odyssey (2013). And, The Color of Compromise: The Truth About the American Church’s Complicity in Racism by Jemar Tisby (2019). We will continue to encourage friends to watch and discuss “Grace, Justice, & Mercy: An Evening with Bryan Stevenson & Rev. Tim Keller” available free on YouTube. And I will encourage the Church to remain in the work for justice over the long haul, and to actively seek forgiveness for patterns of behavior and thinking that deviate from biblical norms of love and a welcoming community of unity in diversity.

We will continue to warn against modern idolatries. Too many evangelicals today have confused Christian and Conservative, failing to recognize that they are not identical and that all political ideologies are idolatries. Francis Schaeffer warned that evangelicals are easily seduced by political agendas of “law and order” because of a superficial reading of texts such as Romans 13. Desiring “personal peace and affluence” they place a misguided faith in the market and then become part of the problem while insisting they are the final bulwark of morality in a relativistic society. In his Letter from Birmingham Jail, Martin Luther King Jr., warned of “the white moderate, who is more devoted to ‘order’ than to justice; who prefers a negative peace which is the absence of tension to a positive peace which is the presence of justice.”

We will be slow to speak and quick to listen. This includes reading. Just Mercy: A Story of Justice and Redemption by Bryan Stevenson (2015). The Sun Does Shine: How I Found Life and Freedom on Death Row by Anthony Ray Hinton (2018). Just Mercy has also been made into a film, and we’ll recommend that as well, and lead discussions on it as we are able. And as I have insisted in these pages and in talks and lectures over the years, we will not truly know our neighbors unless we receive their art. We would do well to listen to the rap music of Killer Mike, for example, and return to listen again to his impassioned and powerful statement at the briefing of the mayor of Atlanta (available on YouTube).

As we listen and read, we will try to amplify black voices. There are plenty of black novelists, thinkers, artists and activists that we can continue to recommend. Their books can be gifts we give to friends and family. Christian faith should comfort the disturbed and comfortless, and discomfort and disturb the comfortable. That’s not Minnesota Nice but it’s a good idea.

We will try to learn. To become anti-racist is not simply a matter of a quick decision but the learned assumption of a new consciousness. We must learn to spot the carefully hidden societal conditions that produce injustice. To notice the expressions of racism in jokes repeated by racists as well as thoughtless friends and relatives and to call them out. To think through how to consistently and courageously confront and speak out against the myths, half-truths and conspiracy theories that suddenly arise in casual conversation.

As I listen and read, process and learn, I will repent as the Holy Spirit convicts me of sin and failure and indifference. For far too long I have trained my ears to hear cries of suffering of the persecution of believers in places like China, the repression of women in places like Iran, and violence in Syria while missing the oppression occurring a few miles from my living room in Minneapolis. I have been guilty of being informed without righteous anger. I have prided myself on reading widely, but I see I have not read widely enough. I need a better education, and if that means I must rearrange some priorities to get it done, so be it.

And we will pray. Not pray in place of action but pray as we act.

Almighty God, you created us in your own image: Grant us grace to contend fearlessly against evil and to make no peace with oppression; and help us to use our freedom rightly in the establishment of justice in our communities and among the nations, to the glory of your holy Name; through Jesus Christ our Lord, who lives and reigns with you and the Holy Spirit, one God, now and forever. Amen.

Acknowledgments: I want to thank Luke Bobo for taking time out of his busy schedule of ministry to give feedback on an early version of this essay. And my wife Margie for the patience to helpfully go over two versions with me. For their thoughtful and generous work in research and editing, I thank Karen Coulter Perkins and Marsena Adams-Dufresne. Without your practical help and passion for justice this article would have been much poorer. I appreciate you all very much.