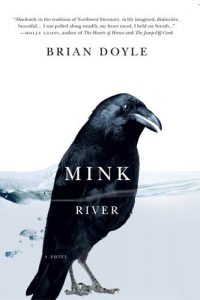

Mink River (Bryan Doyle, 2010)

An extraordinary ordinary

Neawanaka is a tiny village on the Oregon coast, a place where people have lived longer than the stories tell, on the spot where the Mink River flows into the Pacific Ocean. The fictional setting for Brian Doyle’s superb novel, Mink River, Neawanaka has mostly skipped the advance of modernity because it is out of the way and rather disinterested, and so is a place where people, hopeful but broken and troubled, can find meaningful community. It receives about 200 inches of rain annually, is blessed with abundant natural beauty and plenty of fish, and is populated by people who trace their lineage back in stories not just decades but centuries. The village is very small and by all measures insignificant, forgettable even, unless you listen to the stories and sit with the people who tell them. Doyle allows us to do that and as we do hints of something more begin to appear.

Sometimes something changes you forever and often it’s the smallest thing, a thing you wouldn’t think would be able to carry such momentous weight, but it’s like playground teeter-totters, those exquisitely balanced splintery pine planks with a laughing or screaming child at each end, where the slightest change in weight to one end tips everything all the way; and what tipped the doctor into a new life just happened a minute ago. [p. 269]

Margie bought Mink River and read it first. She had noticed essays by Doyle in The Sun, a literary magazine for which we have long had a subscription. She loved his gentle humor, his unabashed Catholic faith, the art with which he tells stories and his way with words. She grieved when he died in May 2017 from a brain tumor at the age of 60. Often when we have guests she takes Doyle’s A Book of Uncommon Prayer down from the shelf and reads aloud. It’s subtitle, 100 Celebrations of the Miracle and Muddle of the Ordinary suggests why we are drawn to it. Margie wasn’t sure what she thought of Mink River when she gave it to me. I hadn’t read 20 pages before laughing aloud twice, and knew I was hooked. Near the end I read more slowly because I didn’t want it to end. It’s a novel to read and cherish and read again.

Doyle divides his prose into little sections, so that once we have met the residents of Mink River we can follow the unfolding of their days without losing track of any of them. It is like having a God’s-eye perspective on the town and its inhabitants, for good and for ill.

Dawn. A pregnant green moist silence everywhere; and then the robins start, and the starlings, and the jays, and the juncos, and the barred owl closing up shop for the night, and a hound howling in the hills, which starts a couple other dogs going, which sets a guy to shouting at the dogs to shut up for chrissake, and someone tries to get a recalcitrant truck going, and the truck just can’t get going, it gasps and gasps and gasps, which sets the owl going again, which sets the mice and shrews and squirrels nearby to chittering, which worries the jays and robins, everyone has the owl shivers, and then the truck finally starts but then immediately dies, which sets the driver to cursing steadily feck feck feck which sets his passenger to giggling and the passenger’s giggle is so infectious that the driver can’t help but laugh either, so they sit there laughing, which sets two crows laughing, which sets the hound to howling in the hills again; and then another car across town starts and a church bell booms brazenly and a house alarm shrills and three garage doors groan up at once and a gray whale moans offshore and there are a thousand thousand other sounds too small or high to hear, the eyelids of a thrush chick opening, the petals of redwood sorrel opening, morning glory flowers opening, refrigerators opening, smiles beginning, groans beginning, prayers launching, boats launching, a long green whisper of sunlight sinking down down down into the sea and touching the motionless perch who hear in their dreams the slide of tide like breathing, like a caress, like a waltz. [p. 223]

The intertwining of relationships and community and nature and events, the weaknesses and strengths of individuals, the quirks and habits that endear and annoy—we come to see them all and love them because these characters, though fictional are so very real.

We meet Worried Man, an old man who tells the old stories and thereby brings meaning and a sense of identity to all who listen. We meet the doctor, a kindly man who cares for the sick in spare bedrooms and smokes only 12 cigarettes a day, each one at a set hour named after one of the Lord’s apostles whose names and stories he reviews thoughtfully as he enjoys his smoke. And there is Moses, a crow rescued from the mud by the old nun and taught to talk by her. There is a man who beats his son, Michael the town cop, and his wife Sara who is pregnant with their third daughter. We meet Cedar, who was pulled out of the Mink by Worried Man mostly drowned, who can’t remember his past but is a faithful and good friend, and hard worker. There is Declan, who fishes, and his sister Grace, who is lost and angry about it but doesn’t want your help. We meet No Horses, and Owen, and Maple Head, and Nora and more—all worth meeting and knowing, and you’ll be better for having done so.

The talking crow should be a signal that this is an enchanted world. Faith is so real that the line between natural and spiritual is simply erased, as it should be. Worried Man can sense pain and fear, rather like an aroma wafting on a breeze, and having tasted it tracks down the source to bring relief and comfort and presence. Moses, the talking crow, talks, and if that sounds weird you haven’t met Moses. But you should. This is a novel that doesn’t merely entertain, it changes how we see people and reality and all the ordinary things that we dismiss as merely ordinary. And it does all this because Doyle, steeped in scripture and myth knows with open hearted love the power of story to enlighten, name, transform and clarify.

Moses, sitting on the football helmet at Other Repair, issues a speech as Owen planes planks. Human people, says Moses, think that stories have beginnings and middles and ends, but we crow people know that stories just wander on and on and change form and are reborn again and again. That is who they are. Stories are not only words, you know. Words are just the clothes that people drape on stories. When crows tell stories, stories tell us, do you know what I mean? That’s just how it is with crow people. We have been playing with stories for a very long time. There are a lot of stories that haven’t been told yet, did you know that? And some stories get lost and don’t get told again for thousands of years. You find them sometimes all lonely. That’s why we have wings, you know. To go find stories. [p. 315]

Doyle breaks rules in Mink River rules that lit teachers insist should never be broken. He composes such long sentences that some go on for pages, though they flow so naturally I never noticed until I stopped and looked. He loves lists, and includes them because lists let us see what the ordinary is about, and in reading them we come to know the people, their lives, interests and concerns more clearly. And without writing a single sentence of science fiction Doyle assumes, correctly, that the ordinary, seen correctly, exists on the edge of a greater reality, full of mystery and wonder and faith and love and enchantment, though now broken and gasping for healing. I entered the world of Mink River and didn’t want to leave, but had to, and when I reentered my own world everything was just a bit richer than I had known.