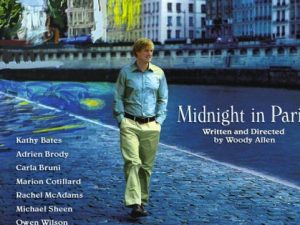

Midnight in Paris (Woody Allen, 2011)

Nostalgia traps the soul

We had a friend who one time mentioned she thought she had been born in the wrong century. “When you consider everything,” she said, “everything from how I’m made to what I prefer to how I’d like to live, I should have been born into the family of a wealthy aristocrat at the height of the old Russian Empire.” She imagined living in a formidable mansion on a sprawling country estate surrounded by acres of carefully tended gardens and meticulous lawns. She would be cared for by an army of servants: chefs, kitchen help, grounds-keepers, maids, and carriage drivers each fulfilling their duties under the watchful eye of a butler who organized everything on the estate and in her life down to the smallest detail. After several months at the estate during the summer a carriage would shuttle her to town where a series of private railroad cars awaited to carry her across the rolling landscape to visit the great cities of Russia: Moscow, St Petersburg, and perhaps across the wastes of Siberia to the port city of Vladivostok. Servants would travel ahead making all the necessary arrangements and whenever possible she would stay in suites in grand hotels, visiting friends and acquaintances over leisurely and lavish dinners. She was not unhappy with her life, understand—it’s just that, in her heart of hearts somehow she sensed her personality would have been specially suited for the life of the Russian aristocracy but had been born too late in history to fulfill that destiny. “That,” she always said, “would have been the life.”

The idea that some golden age existed in the past is a seductive idea. Some people my age, worried about the growing decadence they identify on prime time wish television was still like what they remember from the Fifties, when even married couples were shown sleeping in separate beds. Others prefer the earlier time evoked in the Little House books of Laura Ingalls Wilder, when life was apparently simpler and slower. Some Christians have mentioned they wished they lived in the apostolic era, before the church went astray from the pure gospel of Christ. Some artists see the Renaissance as the golden age, when art was esteemed, artists could find patrons, and when buildings were constructed with careful attention given to the details of every grand façade.

There are problems with all such dreams, of course. They are based on a very selective memory, for one thing. The world’s brokenness is revealed in every age, and even periods of accomplishment are marred with disease, disappointment, and death. There is no golden age in the past, only ones we conjure up in our imagination.

Nostalgia is a poor counterfeit for hope. Looking backwards to a time that can never be retrieved, we miss the opportunity to live in light of something that is worthy of true hope—for the Christian, the triumph of Christ’s resurrection. Nostalgia, a form of sentimentality, fills us with warm feelings and a sense of self-righteous loss that comes from the knowledge that we, unlike our neighbors, are privy to what things could be like if only they listened to us. Such nostalgia generates art that is sentimental and devoid of reality, a political ideology that is rooted in a misreading of history, and a way of life that is defensive because it is always looking backwards trying to retrieve what has been lost.

Woody Allen’s Midnight in Paris is a cinematic exploration of these crucial and very human themes—the idea of a golden age, the pull of nostalgia and the need for hope. Gil (played by Owen Wilson) and Inez (Rachel McAdams) have tagged along with Inez’s parents for a weekend away in Paris just before their wedding. Gil takes a walk alone in the city one night, and while sitting on some steps as midnight strikes, is invited to join a couple at a party. The couple turns out to be Zelda and F. Scott Fitzgerald. A Hollywood scriptwriter who longs to be a serious novelist, Gil is suddenly welcomed into his golden age, the literary and artistic world of Paris at the dawn of the 20th century where he chats with T. S. Eliot and Ernest Hemingway, discusses a new painting with Pablo Picasso, hears Cole Porter sing, watches the lovely Joséphine Baker dance, meets artists Man Ray and Matisse, and has his manuscript read by Gertrude Stein (played wonderfully by Kathy Bates). Adrian Brody performs with delightful surrealist abandon as Salvador Dali, and the encounter with the diminutive but impressive Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec (Vincent Menjou Cortes) is too good to describe in words. Long wanting to escape the hack but highly lucrative writing he is doing in California, Gil not only dreams of his golden age but is given the chance to visit. “It’s a little unsatisfying,” Gil says about the present, “because life is unsatisfying.”

Like all Woody Allen movies, there are numerous subplots as well, and some of the classic themes Allen has long explored in his films appear in Midnight in Paris. Falling in and out of love, the yearning for significance in a world without God, wrestling with an inner sense of being lost in a universe where personal fulfillment seems to be the only guide, the tranquil beauty of great cities that hum with promise, and putting up with snobbish bores that think they know everything and think that everyone wants to hear them talk about it. Midnight opens with shot after shot of Paris, so poignantly stunning that we want to move there, set to the music Allen is known to choose, both classic and breathtaking.

This is not the first time Woody Allen has played with the boundaries of reality. In The Purple Rose of Cairo (1985), set in Depression-era America, a young wife goes to a movie to escape her poverty and abusive husband, only to be shocked when the handsome lead in the film escapes the confines of the screen and sweeps her off her feet. In Purple Rose the line between fiction and real life is transcended by love, just as in Midnight in Paris time no longer keeps pace when desire for true love and a more satisfying life becomes overwhelming.

Allen produces films at a steady pace, most of them ignored by the mass of moviegoers, but seen by an audience that appreciates his work. I am in that group, always eager to watch his next production. In both his life and art, Allen has held up a mirror so we could see the sexual mores, sense of meaninglessness, and yearning for relationship reflected in our modernist and postmodernist world. The picture he has painted on the screen has not always been pretty or consistent, but it has in the main been an honest view, even when it is clear he has to cheat in some way to make the story come out the way he finds most satisfying. In Midnight in Paris Gil meets Gertrude Stein, who befriends him and offers suggestions about his novel. “The artist’s job is not to succumb to despair,” Stein tells Gil, “but to find an antidote for the emptiness of existence.” That has been, I think, Allen’s pursuit as a filmmaker over the years. Every one of his films gives me the impression of having been written and directed on the very edge of the abyss, in full knowledge that the abyss is real, in the outside chance that love will somehow, against all expectations, find a way out.

“This is Woody Allen’s 41st film,” Roger Ebert notes. “He writes his films himself, and directs them with wit and grace. I consider him a treasure of the cinema. Some people take him for granted, although Midnight in Paris reportedly charmed even the jaded veterans of the Cannes press screenings. There is nothing to dislike about it.” Considering the film as cinematic art, I believe Ebert is correct. You may not like this film, but you should watch it, and watch it enough times to get it. Woody Allen is saying something in Midnight in Paris that is worth some careful reflection, and the popularity of this film suggests he is touching a chord in millions of our neighbors. Without something to live for, living at all is almost impossible. If we do not find and intentionally nourish hope, we will be trapped by nostalgia, longing for a golden age that never existed and cannot be retrieved.