Living in Time

Living in time in a fallen world

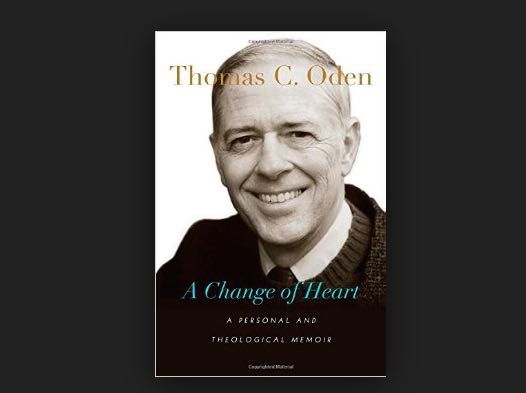

Though his ideas on the topic are much more richly complex than this, Thomas Oden proposes a 3-fold way to summarize human relationships in time. A theologian whose prolific writing has spanned the various movements that have shaped modern liberal theology, Oden has returned to classic Christian orthodoxy after immersing himself as a scholar in the wisdom and teaching—rooted in scripture and the apostolic tradition—of the patristic Fathers and Mothers of the church. In his remarkable memoir, A Change of Heart: A Personal and Theological Memoir (IVP, 2014), he recounts his spiritual pilgrimage and reviews the high points of his thinking and research over the years.

In The Structure of Awareness, which he published in 1969, he apparently (I haven’t read Structure—just his summary in A Change of Heart) proposes a way to think about our human relationships as they are shaped by and lived out in time. Being a scholar intimately in touch with the conditions of life in advanced modernity, Oden’s proposal strikes me a worth some reflection. It seems to echo what I hear in so many conversations with young adults as they search for a sense of significance in our broken world. Oden argues that since we live in time, all of our relationships—with God, others, the created world, and ourselves—are situated in a continuum of future, past and present. That is hardly a novel idea, but Oden’s next move, it seems to me, is full of insight:

the imagined future, which led to anxiety

the remembered past, which led to guilt

the experienced Now, which led to boredom (p. 119)

I wonder if this could not be the epitaph for our broken world in the broken moment in which we are called to live faithfully before the face of God.

I haven’t been able to get these three lines of prose out of my mind since reading them. Future, past, present: anxiety, guilt, boredom—what a horrific, soul-sucking burden to carry. Human beings were not meant to have to bear this. No wonder there are so many who choose suicide, or self-medication, or the myriad distractions offered by career, entertainment, fitness, social activism, or religious busyness. The question is, how should I respond?

I have no illusions about what I can expect to accomplish as one person who also senses the reality of this burden of brokenness. My task is not to change the world but to be faithful, as you are also faithful, trusting that God will choose to do as he wills with our faithfulness.

So I have found myself praying that somehow, by God’s grace, my life may demonstrate the reality of the cross and the empty tomb in a way that speaks to all three: anxiety, guilt and boredom. I will need to face all three honestly myself, and will need to choose the discomfort of walking into the anxiety, guilt and boredom of my neighbor, just as Christ willingly entered ours in incarnation.

It’s been a challenging experience to ask myself whether and how my life demonstrates at least a hint of grace to address all three. One trap is to assume that because none of them plague me at the moment I must have it solved—when I might just be distracted or so subsumed in a pursuit of personal peace and affluence as to be inoculated against fallen reality.

And so it goes. Life in a fallen world while we pray, “Thy kingdom come, thy will be done, on earth as it is in heaven.” It will never be perfect on this side of the king’s return, so let’s not fret over the fact that anxiety, guilt and boredom will always haunt our steps and the steps of those we love. But there can be substantial healing, lovely hints of grace, and bright glimmers of glory demonstrated in quiet ways that point to the power of the gospel.

It’s possible in time, and that makes it worth living for.