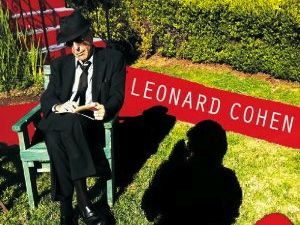

Leonard Cohen, “Banjo” (2012)

A Broken Banjo Bobbing

On Leonard Cohen’s latest album, Old Ideas (2012) he records a song simply named, “Banjo.” It’s a simple, unadorned song, yet the images he weaves into the lyrics are haunting if you let them sink into your imagination.

There’s something that I’m watching

Means a lot to me

It’s a broken banjo bobbing

On the dark infested sea

Don’t know how it got there

Maybe taken by the wave

Off of someone’s shoulder

Or out of someone’s grave

Cohen is an accomplished poet, and the alliteration in the third line focuses our attention just as it has the musician’s. An object, ordinary, out of place, directionless, mysterious yet somehow meaningful, created for beauty but now adrift. This is who we are, who I am. How thankful I am for the clarity this thoughtful Buddhist monk brings to expressing truths I believe yet struggle to speak about in ways that touch on both mind and heart.

There’s something that I’m watching / Means a lot to me. The first two lines are lovely because they could point to anything—and that makes the object of his concern all the more remarkable, It’s a broken banjo bobbing / On the dark infested sea. Instead of something grand and impressive, there is unabashed, unnoticed humility here. Perhaps it is significant that it takes a monk to spot the thing floating in the water in the first place, to identify its shattered existence and find its meaning. Everyone else is too busy hurrying past along the shore looking for something that seems more important.

It’s a fatal condition, and a sad one, a musical instrument both fractured and waterlogged. The music has been silenced. I thought in those terms when I first heard that Earl Scruggs (1924-2012), so justly famous for his 3-finger banjo picking style, had died. I remember the first time I heard him play and wondered how one person could possibly produce such a flowing cascade of notes.

And the image grows more horrible, though at first it seems innocuous enough: Don’t know how it got there / Maybe taken by the wave. That’s what waves do, sweeping up on the sand and sucking away the child’s toys they are using to dig in the sand. But this is no gentle wave, but rather a destructive force worthy of science fiction: Off of someone’s shoulder / Or out of someone’s grave. We remember the impossible memories of the tsunami wiping across the shores of Japan in March 2011, laying waste to houses, family’s lives, and nuclear reactors. It was a moment when videos posted online were too fascinating to ignore yet too awful to watch. Untold tons of rolling water crushing bodies and uprooting cemeteries.

The ancient Hebrew poet spoke of similar brokenness, but in terms of the wilderness that lay just outside the safety of their communities: broken us in the place of jackals / and covered us with deep darkness (Psalms 44:19). Here the crushing of life is so complete that the prophet Isaiah wrote of its breaking is like that of a potter’s vessel / which is smashed so ruthlessly / that among its fragments not a shard is found / with which to take fire from the hearth / or to dip up water out of the cistern (30:14).

As I reflect on these words and images I wonder why the horrors of brokenness are not more equally dispersed in this world. I enjoy reading philosophy and theology and have read the various responses to that question proposed over the centuries, so I can confidently say that there is no answer. No answer that ultimately satisfies, or that ties up all the loose ends of doubt.

Leonard Cohen’s song ends… well, I’ll let you listen to it and decide for yourself.

At this point my hope is in the voice of one who made a promise so audacious as to be preposterous, had he not gone on to endure the final breaking of torture and death, only to rise again as the ultimate Overcomer. When stating his mission Jesus reached back into the text of Scripture to identify himself with the one promised by the prophet Isaiah, the one anointed from beyond the edge of time and space to bind up the brokenhearted (61:1).

The language of the text assures us this is beyond the merely palliative, meaning the rightful King will bring healing to the same depths to which the brokenness extended. We are not told how this will be accomplished, and should not try to figure it out. It is enough to know the promise remains, and in that we can hope.