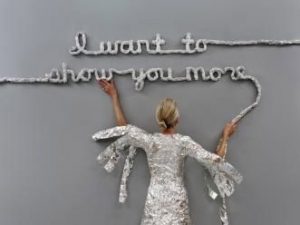

I Want to Show You More: Stories (Jamie Quatro, 2013)

Living faithfully as embodied creatures

In her debut book of fiction, a collection of short stories, Jamie Quatro has bequeathed a deliciously subversive gift to the world, and to the evangelical church.

As literature, I Want to Show You More, is a set of carefully crafted stories, with prose that is simple, and simply powerful in transporting us into the world of her characters. Writing successful short stories is a difficult task—one here, “Imperfections” is only two pages—because no word dare fail to carry the story forward. And stories, to work, have an inner life, a trajectory of purpose, action, tension and consummation that if unheeded keep the reader from the moment of transcendence when we are drawn out of ourselves into the larger reality of imagination. But Quatro never falters. This is more than simply well done. This is writing as a gift, a calling.

As stories, I Want to Show You More is profoundly human, exploring desire, love, frailty, adultery, grief, faithfulness, and faith all within a context of life so ordinary we know it to be of the same reality within which we all move and have our being. Quatro exhibits an imagination schooled in both ancient wisdom and a thoughtful observation for what it means to live in our glorious yet deeply broken world. The novelist Walker Percy remarked that bad stories always lie about the human condition. There are no lies here.

The stories Quatro tells are unsettling, and are meant to be. Not unsettling in the sense of being page-turners, artificially raising tension to keep us reading though I could not set aside the book once I began it. It is unsettling rather, in the same way reality and Scripture are unsettling. Life is always lived in the face of death when mortality and persistent appetites for things we do not and should not have keep a tight grip on the most carefully hidden recesses of our soul. The characters in I Want to Show You More are exposed, sympathetically yet relentlessly, the way we all know we are before the face of God. It is this instinctual and fearful knowledge that propels us to the busyness and other distractions that allow us to achieve efficiency and productivity without ever having to face ourselves. Part of the brilliance of these short stories is that the characters become mirrors, so that the reader, in sharing their humanity is similarly exposed—we share the brokenness even if we haven’t shared in the experience. But perhaps I should speak for myself—this was certainly my experience as I read.

Evangelical Christian readers of I Want to Show You More will find another layer in Jamie Quatro’s fiction. Quatro is a Christian, setting stories in the evangelical world; her husband, Scott is professor of management on the faculty of Covenant College in Lookout Mountain, Georgia. Quatro’s stories are God haunted, not in a narrow religious sense but similarly with Flannery O’Connor’s fiction, in being set in a universe in which God’s reality is the only way things can make ultimate sense.

At times, too, the evangelical world is exposed, sadly accurately for being less than what its members believe it to be. In “Decomposition: A Primer for Promiscuous Housewives,” a woman, deep in grief after ending an affair, seeks help.

You find a Christian therapist named Bobbie in the yellow pages. You choose her not because she’s Christian, but because her office is in Hixson, as far from Lookout Mountain as you can get without leaving the city limits. Bobbie asks you to list ten positive and ten negative memories from your childhood. You tell her that’s not why you came.

You tell her there’s a watermelon in your stomach.

You tell her that every sentence you were in the habit of crafting for the other man—every thought and feeling you were accustomed to sharing—is now taking up residence inside your body.

You tell her you might just need to unload.

I thought you were here because you wanted to save your marriage, Bobbie says.

That too, you say.

What we find, in most cases, she says, is that the woman lacked affirmation in her childhood. We’ll identify the lies from your childhood and, using various techniques such as eye movement therapies, replace them with truths.

What if the truth is I’m in love with him? you say. What if the truth is he was the one I was supposed to marry?

I assume that biblical truth is what you’re most concerned with, Bobbie says.

We talked about having a baby together, you say before you walk out. [p. 11-12]

In “The Anointing,” a wife asks the elders to pray for her husband. Mitch no longer gets out of bed, depressed since losing his successful medical practice after becoming addicted to painkillers. Increasingly desperate, Diane is trying all she knows to save her family, and begins to wonder if perhaps there is nothing there that will turn the tide.

Diane wanted to believe the anointing would be that thing. But she doubted it would work. Her faith was waning. What if it was all a crock, made up to quiet fears of not existing? Near-death experiences, angelic visitations, visions—all just neurons firing, a highly evolved response system to keep the human race from going insane? [p. 88]

The details of this story made me cringe, which made the surprisingly revelation of grace at the end all the more miraculous. In “Demolition,” the only story in which irony plays a prominent role, a congregation dismantles their church after a deaf man confesses his disbelief and little sections of their stained glass windows begin inexplicably popping out of their frames. Then the steady dismantling of belief begins until Nature and God feel identical, the siren call of paganism far closer to a shallow evangelicalism than any of us would have suspected.

In a poignant story that never wanders into sentimentality, “Better to Lose an Eye,” a fourth grader struggles with the embarrassment that overcomes her in public over her pious grandmother and wheelchair bound, quadriplegic mother. “1.7 to Tennessee” introduces us to Eva Bock, an 89 year old who walks to the post office because she has written a letter to President Bush. She doesn’t return but the White House responds. Some of the stories are snapshots of life containing the same characters. “Here” introduces us to a young widower trying to pick up his life after his wife has died from cancer. Later in the book is “Georgia the Whole Time,” in which the wife tries to tell her children she is dying.

This past Sunday my pastor preached from a text written by the Hebrew prophet Hosea. It is not a comfortable text, too sexually charged for most evangelicals to rest in its message. Hosea is told by God to marry a promiscuous woman, a prostitute. So he marries Gomer and they have children, but then Gomer leaves for her old lifestyle. Perhaps life with a prophet was too tame after the adventures she had experienced. Whatever the reason, Gomer left, and God told Hosea to go win her back. By this time Gomer was for sale in the market, which history tells us was a brutal place, women thrust nude onto a public stage as the bidding commenced. My pastor speculated that Gomer was shamed, and that perhaps in buying her Hosea covered her nakedness as Christ covers his people’s shame with righteousness. It is a lovely image, and a sweet picture of redemption. But as I listened I wondered if perhaps a different speculation isn’t also possible. Is it possible Gomer was not shamed on that stage but rather enjoyed the exposure? She was, after all, the one who chose to leave, choosing to seek satisfaction in a series of lovers. Perhaps Gomer was rather more like the women who preen on the covers of glossy magazines spread out for our gaze on racks next to newspapers. Either way, we will fail to understand Hosea’s message if we fail to understand the true nature of desire and fully embrace a biblical view of what it means to be embodied creatures. Jamie Quatro’s stories help us do both.

And to Christians who are offended by the language her characters use, I would respond Quatro is writing truthfully. If you do not grasp that you probably need to make non-Christian friends. To those offended by the sexuality, reread your Bible and look around at life. Living righteous lives does not include sheltering ourselves from reality.

A final excerpt from Qautro’s story, “You Look Like Jesus.”

I didn’t keep the photographs he sent. At the time, deleting them felt like a way to esteem my husband.

I remember the important ones. A cell phone picture he took during a long run: waist-up, eyes squinting, face shining with sweat. Rows of white tombstones behind.

Here I am, his text said. Please call.

You’re a beautiful man, I said when he answered.

You have no idea how much I needed to hear that, he said.

Another one: he was sitting on the floor, stretching, legs long in front of him, feet bare.

People tell me I have nice feet, he said.

I looked, zoomed in, looked again.

They’re shaped like mine, I said.

Show me, he said.

I took my shoes off and angled the computer down, clicked the red camera.

That confirms it, he said. We’re related. From the same soul-cluster.

I want to show you more, I said. [p. 101]

Book reviewers are supposed to say something negative, but I have no criticisms here. Only a hope that Jamie Quatro will keep writing.