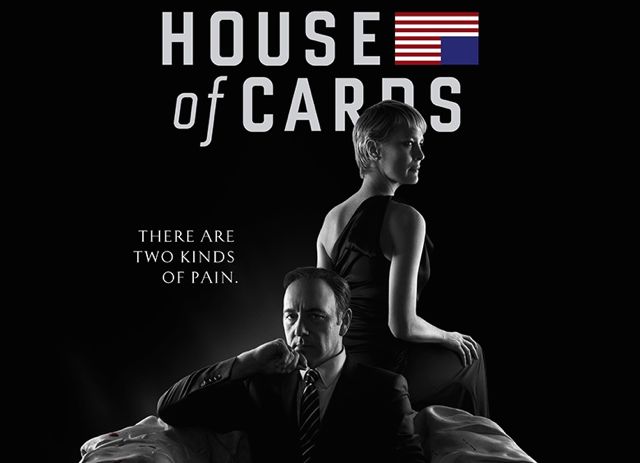

House of Cards (Beau Willimond, 2013)

Where cynicism reigns

In the traditional Christian view of things, the temptation to feel, think, and live in ways that are less than virtuous comes from one or more of three sources: the flesh, the devil, and the world. The flesh refers to what is within us, our broken nature that tends towards selfish pride, and tempts us to substitute personal gain or pleasure for what is right and good. The devil refers to the spiritual forces of personal evil that prowl the darkness seeking to distort grace, subvert hope, undercut redemption and in the end, devour our very being. We cannot always tell when the flesh ends and the devil begins, but identifying the exact line is of little importance since the end of both are identical, namely sin, corruption, some destructive impulse, and ultimately, death. This is why sharpening our conscience—aligning it with true standards of virtue, and rooting out legalisms that distort the true meaning of goodness—is such a vital task.

The third source of temptation, the world, can be the most difficult to identify, because in some ways it exerts the most subtle influence of the three. The world refers not to human culture, but to the systems, institutions, loyalties, ideologies, and values that order the society of fallen humanity in ways that in part or in whole resist God’s kingdom. No system—political, economic, tribal, nationalistic, church, or any other—in a fallen world is fully pure, so none are able to fully provide for complete human flourishing. It is why we pray, as our Lord taught us, that God’s kingdom would be on earth as it is in heaven.

Sometimes the systems of the world are so perverse (think North Korea), the oppression so obvious that the evil is abhorrent to everyone. For most of us, especially those of us who live in the 21st century West, the world system in which we live is mostly good, partly bad for human flourishing, so we simply go with the flow. Since no world system, however, is the equivalent of God’s kingdom, we must always be alert to ways ours will tempt us in directions contrary to the reign of Christ as Lord.

We live embedded in the world, like the proverbial frog in a pot of hot water. The difficulty comes from the fact that the water we swim in is our permanent environment, so it’s easy to miss the fact that the temperature is rising. As the water temp rises, we hardly notice. We’ve just become accustomed to the world. This is why developing skill in discernment is so vital in the process of deepening our discipleship. Being able to identify the characteristics of our world means we’ll be able to resist being molded into its shape.

Without taking the time to defend this proposition, I’d suggest one characteristic of the world in which we live is cynicism. It’s not merely out there, but is in the air. It often shows up in ways that make us laugh, and seems to be caught as easily as the common cold.

“Cynicism, as we use the word today,” Dick Keyes says, “has to do with seeing through and unmasking positive appearances to reveal the more basic underlying motivations of greed, power, lust and selfishness. It says that every respectable public agenda has a hidden private agenda behind it that is less noble, flattering and moral.” Because cynics essentially belittle those who oppose them or hold differing opinions, beliefs and values, they imagine that they occupy the moral high ground. After all, in a fallen world some measure of suspicion is wise—things are often not as they appear. Since people who are different from us are finite and fallen, finding some inconsistency or something less than admirable in them is always possible. Though the cynic assumes the moral high ground, in reality, of course, such cynicism is doubly wrong: it refuses to treat others with the full dignity of being created in God’s image and it assumes a level of insight into others that only God possesses. Still, cynicism is an essential part of our world, hidden in the blather of pundits and media commentators, implicit in articles and talks, animating witty conversations in coffee houses, and provoking knowing laughter in Christian audiences when speakers describe non-Christian beliefs and actions in ways believers find silly.

No Christian wants to resist the values and realities of God’s kingdom. None of us want to do things that will undercut human flourishing—our own or anyone else’s. None of us set out to intentionally become more cynical. It simply happens, if for no other reason that something so ordinary and ubiquitous begins, after a while, to feel, well, natural. And so it goes.

There are several ways to become sensitized to the characteristics of the world—to what earlier generations called “the spirit of the age,” the things built into the structures, attitudes, and institutions of our world that systematically resist God’s kingdom. One is by listening to the voice of discerning observers. In the case of cynicism we can be grateful for Dick Keyes’ superb study, Seeing Through Cynicism (IVP, 2006). If you haven’t read it, please do. By the end you will still see our world through a glass darkly, but with far greater clarity than before.

Another way to become sensitized is to read the work of those who lived in very different settings from our own. For the Christian, this can include the Puritans, the Reformers, the early church Mothers and Fathers, and the growing number of Christian voices from the developing world. Seeing through their eyes means seeing through eyes molded by pressures different from our own setting.

Another source of insight is art. Artists are often sensitive to what lies in the shadows, and they can use their creativity to shed a glimmer of light onto what is otherwise hidden. Good storytellers excel in this task. The ancient Hebrew prophet Nathan, for example spoke truth to power in just this way with a story about a wealthy man’s pet lamb (2 Samuel 12) and Jesus uncovered the hidden darkness in a man’s soul by telling a story about a traveler and a band of thugs (Luke 10).

We listen to good stories, are drawn in, and in the end made to see daily, ordinary reality with greater clarity because our imagination has been enlarged and enlivened. The story allows us to see with greater clarity things we had not noticed previously or perhaps had looked past as unremarkable, insignificant or natural. Abstract notions like cynicism are made incarnate, and so something hiding in plain sight can be felt and seen and heard and touched. Just hearing the truth about something is not sufficient—truth must be incarnated in story if it is to flower into its full meaning and goodness. This is the nature of reality.

House of Cards, an original Netflix series, is not just good television it is a brilliantly disturbing study in cynicism. (As I write this, two seasons of 13 episodes have been released, with word that season three is being produced.)

The story line can be summarized in three simple statements. First, imagine key players in Washington, DC: a member of Congress rising rapidly in the nation’s leadership; the CEO of a major nonprofit organization awash with money and worldwide influence; several journalists at a major newspaper and an influential news blog; some wealthy business leaders and financiers; and a host of political operatives and lobbyists who settle for nothing but winning. Then, imagine them as completely cynical. They all believe the end always justifies the means, as long as the end being won is what they want. Imagine them so hungry for their own ends that they actually believe their ends are always for the common good. And then, House of Cards, asks, what might that look like? Why, the series seems to say, it looks remarkably like Washington DC.

For all its high production values and compelling story line, House of Cards is a difficult series to watch. The cold political calculation where power always trumps people is chilling, even when it is supposedly used for the common good. Everyone is convinced they can see through everyone else, and principled compromise, so essential if the common good is actually to be achieved in a free society, is replaced with a single-minded determination to best one’s opponents by raw political, economic, and rhetorical power. I am not easily scared by what I see on the screen, but sometimes the icy maneuvering of Congressman, and later Vice President Francis Underwood, played with an intense brilliance by Kevin Spacey, is frankly frightening.

House of Cards is scary, not because it is a horror story, but because it relentlessly shines light into a dark corner of my soul and my society, and what is shown to be there is not good.