Pluralistic World / Spirituality

Finding hope in a pandemic

The coronavirus is a terrible scourge, leaving a devastating trail of illness, death, strained relationships, loneliness, economic hardship and business loss in wide swathes across the globe. In this it is similar to the numerous sinister plagues that have ravaged the world throughout history—Black Death, yellow fever, influenza, cholera and more.

What we are enduring in the coronavirus pandemic seems so novel to most of us that it’s worth remembering that living through a pandemic is not really new. Of course, this fact does not make COVID-19 more bearable; it merely reminds us of the brokenness of our world and that for all our heroic efforts, remarkable science, medical advances and technological expertise we are still unable to save ourselves. The speed and spread of infection, scientists tell us, is not surprising given the nature of the disease, but it was shocking how quickly it upended our lives and perspectives.

Margie and I are sheltering in place, as ordered by Minnesota Governor Tim Walz when he wisely told us all to stay home. We are writers, a solitary vocation, but this isolation feels different. Our home backs up to the edge of Hidden Valley Park (appropriately named for a time of quarantine), thickly wooded with steep ravines leading down to the Credit River (appropriately named during a time of economic downturn). When we moved in, we named our home, The House Between, where we are in the years between the main period of our lives and ministry, and our deaths (also, as it turns out, appropriately named).

“We face a doleful future,” Dr. Harvey Fineberg, former president of the National Academy of Medicine, says. He sees “an unhappy population trapped indoors for months, with the most vulnerable possibly quarantined for far longer.” Margie and I are in that category, both by age and with underlying health issues. “If we scrupulously protect ourselves and our loved ones,” Donald McNeil reports in The New York Times, “more of us will live. If we underestimate the virus, it will find us.”

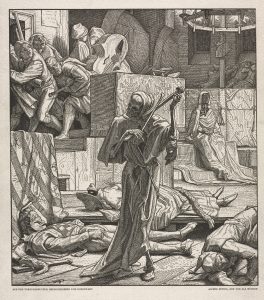

It will find us. Uncomfortable words. Today, under the spell of medical science we see death as a physical phenomenon, an impersonal event explainable by natural causes. And so, it is. But when it comes close, or snatches someone we love, or hovers unnervingly around us this left-brain explanation by itself seems somehow insufficient. Death reminds us of greater realities, principalities and powers that are at work beyond the reach of science to observe, measure and replicate. To see properly here a right-brain vision is also necessary, so that art complements science to align our perspective more closely with the nature of reality. And so, we turn to the artist for help, allowing our imagination to join our mind in grasping the horror of pandemic.

In 1850, a German artist, Alfred Rethel (1816-1859) created a woodcut (approximately 12 inches square), titled, “Dance of Death: Death the Strangler.” Here death is personified, as a skeletal phantom, dancing to its own music played not with a violin bow but a bone. Bodies lie about in the street, abandoned corpses, and villagers flee fearing infection. Those that flee also carry musical instruments—cello, violin, oboe—but their music is stilled, in fear perhaps or anguish or in the rush to escape. The only music is that played by Death and it is the music of despair. In the background a gruesome creature, Illness or Infection rests, holding a cruel scourge with sharp metal studs on multiple flails. It pauses in inflicting its pain, in no hurry because the pandemic will not quickly flee or fade. One person covers their face, hoping to avoid the illness and the scent of decay, but neither of the phantoms are concerned anyone will escape. Perhaps not today, or even tomorrow, but in the end, Death will not be avoided.

Rethel’s woodcut is art, a metaphor, a creative depiction of reality. It is imaginative and allusive not definitive, right-brain not left. In contrast, Merriam Webster defines coronavirus as, “any of a family (Coronaviridae) of large single-stranded RNA viruses that have a lipid envelope studded with club-shaped spike proteins, infect birds and many mammals including humans, and include the causative agents of MERS, SARS, and COVID-19.” We need both depictions to see properly and are mistaken to place them in opposition.

The media and various officials from a variety of institutions provide daily pandemic updates. We want to remain informed without being overwhelmed, which takes intentionality and thoughtful care—in a word, discernment. Complicating this is the need to wade through the endless political posturing, the ideological debates, dangerous distrust, the myths and reckless suggestions for cures, the obviously incorrect claims, the appalling lack of leadership and polarizing protests that seek not to persuade but to bully. Even setting aside all of that, the flood of helpful, legitimate data and information is continuous and feels at times like a tsunami: How many have fallen ill, how many have been hospitalized, how many of the hospitalized are in the ICU, how many ventilators are available, whether the supply of personal protective equipment is sufficient, how many are tested, how many more test kits and reagents are needed, how many have died, how many have recovered.

We must realize that all this updating and commentary is not merely neutral data or information. Together it works to shape our perspective, our view of where and who we are, of how we see ourselves, our world, the pandemic and our future. Perspective matters. It slowly becomes the story that shapes how we interpret what is happening around us, how we should live and what we should expect.

Wisdom suggests we must find a way to check our perspective. If our view of things is simply fed by the daily updates, political agendas and pundits’ commentary, we are likely to be swept off in all sorts of directions. Better to be discerning: Am I seeing things correctly? Is the story I am telling really reflective of life and reality or does it merely reflect how conformed I am to a fallen world? And does my story take into account the bigger Story to which in my hearts of hearts I have pledged my allegiance?

I would suggest that there are at least three touchstones by which we as Christians can check our perspective during a pandemic:

1. Remember fallen reality.

2. See the coronavirus Christianly.

3. Reexamine our basis for hope.

Remember fallen reality

As a society we have gone to great effort and expense to keep death at arm’s length. Not too long ago the average American child would help their grandmother with butchering a hen for Sunday lunch. Along with advances in medical science there has arisen a funeral industry that has made obsolete the necessity of caring for and sitting with the body of a deceased loved one. The family physician, who used to include in their calling the task of informing the family when death is near, now uses technology and extreme measures to keep death at bay. There is nothing inherently wrong with any of that, except if it causes us to somehow be disconnected with the reality of the fall, including the fact that each of us, without exception, will die.

“We are alienated from ourselves: that is, within each of us we find the disintegrating power of sin,” Jerram Barrs says.

This separation within our own persons is also expressed in our bodies. Pain, sickness, and the debility that comes with advancing age demonstrate this physical corruption. Death, our final enemy, manifests this reality most fully as it tears apart body and spirit and brings our bodies down to the grave.

Truly believing in the reality of the fall should help us maintain perspective during the pandemic. All the coronavirus has done is remind us of this fallen reality. In that sense, nothing much has really changed.

In 1948, C. S. Lewis published a magazine article, “On Living in an Atomic Age.” At the time, nuclear weapons were new and horrifying, especially to the people of Great Britain who had suffered horribly through the Blitz in World War II. Scientists and politicians warned that humankind now had the capability to wipe life from the earth. The terrible images, death toll and massive destruction inflicted on Hiroshima and Nagasaki caused people to pause and wonder whether dropping them was just, and to feel fearful. Their perspective on life had been altered.

But Lewis challenged the new story they were telling themselves and each other. In his essay he argued we must take the nature of fallen reality seriously. He begins this way:

In one way we think a great deal too much of the atomic bomb.

“How are we to live in an atomic age?” I am tempted to reply:

“Why, as you would have lived in the sixteenth century when the plague visited London almost every year, or as you would have lived in a Viking age when raiders from Scandinavia might land and cut your throat any night; or indeed, as you are already living in an age of cancer, an age of syphilis, an age of paralysis, an age of air raids, an age of railroad accidents, and age of motor accidents.”

In other words, do not let us begin by exaggerating the novelty of our situation. Believe me, dear sir or madam, you and all whom you love were already sentenced to death before the atomic bomb was invented: and quite a high percentage of us were going to die in unpleasant ways. We had, indeed, one very great advantage over our ancestors—anaesthetics [sic]; but we have that still. It is perfectly ridiculous to go about whimpering and drawing long faces because the scientists have added one more chance of painful and premature death to a world which already bristled with such chances and in which death itself was not a chance at all, but a certainty.

This is the first point to be made: and the first action to be taken is to pull ourselves together. If we are all going to be destroyed by an atomic bomb, let that bomb when it comes find us doing sensible and human things—praying, working, teaching, reading, listening to music, bathing the children, playing tennis, chatting to our friends over a pint and a game of darts—not huddled together like frightened sheep and thinking about bombs.

Whatever threat we face, whether atomic weapons in 1948 or the Black Plague in London in 1665 or the COVID-19 pandemic in America in 2020, our perspective needs to be grounded in reality—and reality is that life is fallen, the world is broken, and death awaits us all. This is not pessimism but realism. The fact that something is deathly wrong is one of the few, perhaps the only point on which all religious and philosophical worldviews agree. Everyone must account for death and suffering and live accordingly. We may choose to ignore it, believe it is an illusion, escape into drugs, busyness or some other distraction, but eventually death finds us.

This was true before the pandemic and will remain true after it is past. It is not what God intended to be normal in the world he created, but it is our normal in this abnormal world. This provides a helpful check on our perspective, namely, that things haven’t changed as much as we might imagine. The coronavirus is new, but reality remains. For the Christian this means that whether we feel threatened or not, our calling remains constant, to be faithful in the ordinary and routine of life. It was so before the pandemic and will be so once it is past. Our ordinary and routine is different, of course, but that isn’t entirely unprecedented either.

See the coronavirus Christianly

My natural tendency is to see Margie and myself sheltering at home dangerously surrounded by the pandemic, praying that God, who is out there, will keep us safe. But I would argue that a holy spirited perspective is to see us sheltered safely in Christ, with the pandemic out there safely under the sovereign providence of God.

Remember what St. Paul writes in Colossians when he speaks of a great mystery of the faith. He claims our redemption in Christ means that we are actually not out on our own, but in him, or as the apostle puts it in Colossians 3:3: our life “is hidden with Christ in God.”

Now compare this to what the Hebrew poet says in Psalm 46—it’s repeated twice like a refrain. “The Lord of hosts is with us; the God of Jacob is our stronghold.” The first line reminds us that no matter how dark our days, we have not been abandoned. And the Lord who is with us has suffered his own darkness, separation and feared abandonment. The second line reminds us of where we have been placed by God’s grace. A stronghold is a place we shelter in danger, a place of safety where the enemy is kept at bay.

This means I can be realistic without panic, I can plan without hoarding, and I can be content to serve in love because I am in the shelter and refuge who is the God who loves me and his world and has not abandoned it. A distinctly Christian or biblical perspective reveals that Margie and I are not in a vulnerable spot, the coronavirus is. We’re ensconced in the safest place there is.

This should be reflected in our choices, our attitude, our gratitude and our hopefulness.

Reexamine our basis for hope

Besides remembering the nature of fallen reality and being certain to view the pandemic through the lens of Holy Scripture, it also helps to reflect again on the meaning of life and the possibility of hope.

For Lewis in his essay on atomic weapons this meant thinking about Naturalism, the popular explanation for things in his day. So, he took Naturalism to its logical conclusion:

If Nature is all that exists—in other words, if there is no God and no life of some quite different sort outside Nature—then all stories will end in the same way: in a universe from which all life is banished without possibility of return. It will have been an accidental flicker, and there will be no one even to remember it.

And in writing this, he sounds very much like some of the voices of our own day, 72 years later in 2020 during the coronavirus pandemic.

Consider, for example, the voice of Maria Popova, author of the book, Figuring (2019) and the popular blog, Brain Pickings. In a Brain Pickings email titled, “Figuring Forward in an Uncertain Universe,” Popova writes: “A couple of days ago, I received a moving note from a woman who had read Figuring and found herself revisiting the final page—it was helping her, she said, live through the terror and confusion of these uncertain times. I figured I’d share that page—which comes after 544 others, tracing centuries of human loves and losses, trials and triumphs, that gave us some of the crowning achievements of our civilization—in case it helps anyone else.”

This, then, from the final page of Figuring by Maria Popova:

Meanwhile, someplace in the world, somebody is making love and another a poem. Elsewhere in the universe, a star manyfold the mass of our third-rate sun is living out its final moments in a wild spin before collapsing into a black hole, its exhale bending spacetime itself into a well of nothingness that can swallow every atom that ever touched us and every datum we ever produced, every poem and statue and symphony we’ve ever known—an entropic spectacle insentient to questions of blame and mercy, devoid of why.

In four billion years, our own star will follow its fate, collapsing into a white dwarf. We exist only by chance, after all. The Voyager will still be sailing into the interstellar shorelessness on the wings of the “heavenly breezes” Kepler had once imagined, carrying Beethoven on a golden disc crafted by a symphonic civilization that long ago made love and war and mathematics on a distant blue dot.

But until that day comes, nothing once created ever fully leaves us. Seeds are planted and come abloom generations, centuries, civilizations later, migrating across coteries and countries and continents. Meanwhile, people live and people die—in peace as war rages on, in poverty and disrepute as latent fame awaits, with much that never meets its more, in shipwrecked love.

I will die.

You will die.

The atoms that huddled for a cosmic blink around the shadow of a self will return to the seas that made us.

What will survive of us are shoreless seeds and stardust.

Or consider the voice of Brian Greene, professor of physics and mathematics at Columbia University. This from an online conversation:

When you recognize that we are the product of purposeless, mindless laws of physics playing themselves out on our particles — because we are, all, bags of particles — it changes the way you search for meaning and purpose: You recognize that looking out to the cosmos to find some answer that’s sort of floating out there in the void is just facing the wrong direction. At the end of the day, we have to manufacture our own meaning, our own purpose — we have to manufacture coherence… to make sense of existence. And when you manufacture purpose, that doesn’t make it artificial — that makes it so much more noble than accepting purpose that is thrust upon you from the outer world.

And this from Dr. Greene in the final pages of Until the End of Time: Mind Matter, and Our Search for Meaning in an Evolving Universe:

We are ephemeral. We are evanescent.

Yet our moment is rare and extraordinary, a recognition that allows us to make life’s impermanence and the scarcity of self-reflective awareness the basis for value and a foundation for gratitude…

We exist because our specific particulate arrangements won the battle against an astounding assortment of other arrangements all vying to be realized. By the grace of random chance, funneled through nature’s laws, we are here…

As we hurtle toward a cold and barren cosmos, we must accept that there is no grand design. Particles are not endowed with purpose. There is no final answer hovering in the depths of space awaiting discovery. Instead, certain special collections of particles can think and feel and reflect, and within these subjective worlds they can create purpose. And so, in our quest to fathom the human condition, the only direction to look is inward. That is the noble direction to look. It is a direction that forgoes ready-made answers and turns to the highly personal journey of constructing our own meaning. It is a direction that leads to the very heart of creative expression and the source of our most resonant narratives. Science is a powerful, exquisite tool for grasping an external reality. But within that rubric, within that understanding, everything else is the human species contemplating itself, grasping what it needs to carry on, and telling a story that reverberates into the darkness, a story carved of sound and etched into silence, a story that, at its best, stirs the soul.

I want to be careful here because I am not a secularist. I deeply appreciate Greene’s ability to explain the discoveries of science and mathematics in a way I as a nonscientist could begin to grasp their meaning. And I want to take Greene’s and Popova’s beliefs seriously. But. If the cosmos is finally an impersonal space of no meaning or purpose, then any sense of meaning and purpose we project from within ourselves is finally meaningless as well.

Both Popova and Greene are good writers, using well crafted prose to make their point with brilliance. But. It is one thing for good writing to enhance and exposit the substance of an idea, but it is quite another when good writing is used to hide a lack of substance. As a writer I appreciate good writing and know the delight of working hard to craft prose that delights as well as informs. I have no doubt that secular readers might find solace in what Popova and Greene suggest. We naturally feel a sense of awe when we consider our place in the physical universe within the scale of time and space that overwhelms us. But. On what basis can we assume those feelings have any meaning, or that the meaning we ascribe to them is not meaningless? The appeal of this sort of writing is known to me. In my tribe there is an almost insatiable market for devotional literature, some of which involves a story that tugs at heartstrings along with a few favorite Scripture verses (out of context) woven together with a few well-beloved phrases in the dialect spoken in Sunday school classes. Here sentimental writing does not help believers deepen their faith and life but rather substitutes warm feelings for spiritual growth, mature reflection and robust worship.

“By the grace of random chance,” Greene writes, “funneled through nature’s laws, we are here.” As a Christian, I must say, No. There is no grace here, nor is there the possibility of grace. Greene is borrowing a Christian term and misapplying it to make his case sound better than it is. Random chance can be described in many ways: impersonal, blind, unfeeling, but one thing it is not is gracious. Grace is not a secular concept but a profoundly Christian one, and the etymology of grace has roots in 12th century Old French meaning “God’s unmerited favor.”

I hope you read C. S. Lewis’ essay. And I would agree with him that the secular reductionistic perspective on life is insufficient for real hope in the face of death. Depending on an inner sense of meaning in a meaningless cosmos is the counsel of despair. I do not mean that Popova and Greene are in despair—from their writing they seem positive and optimistic. I use despair here in a more technical or philosophical sense, to define a romantic and irrational conclusion that is unrelated to their insistence that reality can be known only through science. This is blind faith, a leap in the dark, and speaking personally as a Christian I would say that I could never muster that much faith. To argue for meaning to arise from meaningless is to counsel a blind embrace of meaninglessness while renaming it, against all evidence, meaningful. I find no cause for hope in this.

I realize that for most today this is finally an issue of faith, commitment and belief, not argument, reason and evidence. It is love, not debate, that matters. Still, I would insist there is a far better story to account for meaning and hope in the midst of a pandemic. Meaning, purpose and hope found in the personal infinite God who created all things, who loves what he made and is redeeming all things. This God is not acquainted with pain, illness and death only theoretically because he entered human history in the person of Christ, suffered and gave up his life, going through death so that life in him was won, eternally. And the guarantee of the story is not a leap in the dark but a historic fact, in space and time, testified to by a skeptical—and still growing—crowd of witnesses: an empty tomb, a risen Lord.

And in this I see sufficient reason for hope.

Source: Fineberg and McNeil in “The Coronavirus in America: The Year Ahead” by Donald G. McNeil, Jr. in The New York Times (April 18, 2020). Merriam Webster online . Jerram Barrs from “Eight Biblical Emphases of the Francis Schaeffer Institute” in Covenant Magazine (Covenant Theological Seminary; Issue 32, 2020) p. 39. “On Living in an Atomic Age” in Present Concerns: Essays by C. S. Lewis (New York, NY: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich; 1986) pp. 73-74. Maria Popova online, specifically here. Figuring by Maria Popova (New York, NY: Pantheon Books; 2019) page 545. Brian Greene in conversation online. Until the End of Time: Mind Matter, and Our Search for Meaning in an Evolving Universe by Brian Greene (New York, NY: Alfred A. Knopf; 2020) pp. 322-326.