Doubt, Faith, and Knowledge

If you read the New Testament you will probably notice that some of the disciples of Jesus are mentioned quite often. Peter shows up regularly in the text, and so does John—their names each appear in the Gospels at least a hundred times. On the other hand, other of the disciples are mentioned hardly at all. One of those who didn’t rate much attention is Thomas.

We know little about him from the Scriptures except that he was a follower of Christ and apparently a twin. Several times in St John’s Gospel (11:16, 20:24, 21:2) he is referred to as “Thomas (called Didymus).” Thomas means twin in Aramaic and Didymus means twin in Greek, so he essentially had the same name in both languages. Thomas appears with the other disciples in passages that list their names (Matthew 10:3; Mark 3:18; Luke 6:15; John 21:2; Acts 1:13), but other than that he is mentioned only four times, and then rather briefly (John 11:16; 14:5; 20:24, 26; 20:27, 28). Complicating the issue, the way he’s mentioned makes us remember him not as The Twin, which is apparently how his friends knew him, but as the disciple who doubted. So he’s remembered as Doubting Thomas. Which in terms of faith, doesn’t seem to be the best of all possible reputations for an apostle. As I was growing up people in the church would say, “Now, don’t be a doubting Thomas,” as if that is somehow encouraging (which it wasn’t) and as if evoking his memory will somehow make us believe more readily (which it didn’t).

A significant thing about Thomas’ doubt is that it involved Jesus’ resurrection, which is supposed to be at the center of our faith as Christians, the historical fact on which we are to base our hope. The story of his doubt, it seems to me, is a story not of disgrace, but of grace. So, if you have ever found yourself doubting, like I have, or if you know someone who has doubted, the story of The Twin and the resurrection is good news.

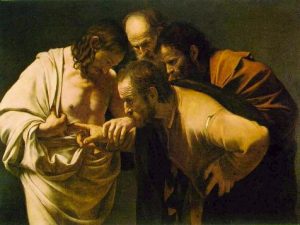

Now Thomas (called Didymus), one of the Twelve, was not with the disciples when Jesus came. So the other disciples told him, “We have seen the Lord!” But he said to them, “Unless I see the nail marks in his hands and put my finger where the nails were, and put my hand into his side, I will not believe it.”

A week later his disciples were in the house again, and Thomas was with them. Though the doors were locked, Jesus came and stood among them and said, “Peace be with you!” Then he said to Thomas, “Put your finger here; see my hands. Reach out your hand and put it into my side. Stop doubting and believe.” Thomas said to him, “My Lord and my God!” Then Jesus told him, “Because you have seen me, you have believed; blessed are those who have not seen and yet have believed.”

Jesus did many other miraculous signs in the presence of his disciples, which are not recorded in this book. But these are written that you may believe that Jesus is the Christ, the Son of God, and that by believing you may have life in his name. (John 20:24-31)

Perhaps because so little is revealed about Thomas in the Scriptures, a number of legends grew up about him in the first couple of centuries after his death. There is, for example, an apocryphal book called The Acts of Thomas, dating to the third century and originally written in Syriac, which purports to tell us some of his life and ministry after Christ’s resurrection. Though The Acts of Thomas has never been accepted as canonical, it does support a tradition for which there is other evidence in history. That tradition states that as the apostles spread out to the ends of the earth preaching the gospel, Thomas ended up in India. Today there remains a Mar Thoma Syrian Church in India, with ancient roots that they proudly trace to St. Thomas.

In any case, in The Acts of Thomas we’re told that Thomas wasn’t particularly pleased to be called as a missionary to the Indian subcontinent. The story goes that after Christ’s death and resurrection, but before his ascension into heaven the apostles divided up the world, so that together they might be faithful to the Lord’s command that they go into all the world with the gospel. When the lots were cast, Thomas got India, but he didn’t want to go. He wasn’t strong enough for the long arduous journey. “I am a Hebrew man,” he is reported to have said, “how can I go among the Indians and preach the gospel?” That night Jesus appeared to him, and assured him that his work in India would be filled with grace, but still Thomas refused to change his mind. “Wherever you would send me, send me,” he told the Lord, “but somewhere else, because I won’t go to India.”

About that time a wealthy merchant from India named Abbanes arrived in Jerusalem. He had been sent by his king to find a skilled carpenter, and so went to the marketplace where he happened to meet Jesus who told him he had a slave who was just the carpenter he was looking for. After Abbanes and Jesus had worked out the details for the sale, Jesus took the merchant to meet Thomas. Pointing to Jesus, Abbanes asked Thomas if this was his master, and Thomas acknowledged that, indeed, Jesus was his Lord. “I have bought you from him,” Abbanes told him, and before long Thomas was on his way to India. The king who had purchased him eventually became a Christian, the story goes, and soon a thriving church had been established. And though no one knows for sure how St. Thomas’ life ended, The Acts of Thomas says that he was martyred for his faith, after the wife of a powerful Indian official was converted to Christianity. The husband was displeased at his wife’s profession of faith, and arranged for Thomas to be killed.

The legend of Abbanes taking Thomas to India against his wishes has a certain charm, I think, but the text of Scripture I quoted earlier contains a far deeper wisdom. It provides reasons for faith, unveils what knowledge is truly vital, and reveals that doubters are welcome among the people of God. Doubting, it turns out, doesn’t disqualify us from being a disciple. Doubt isn’t unbelief; it’s faith with honest questions.

It’s been three days since the crucifixion, and now, early on Sunday morning before dawn, Mary Magdalene walks to Jesus’ tomb, and is shocked to find it open. The huge stone they had rolled over the entrance has been rolled back, they can see right inside, and the body isn’t there. She runs to find Peter and John. “They have taken the Lord out of the tomb,” she told them, “and we don’t know where they have put him!” The two disciples run to the tomb, John wins the footrace, and arriving first looks in and sees the linen burial cloths they had wrapped Jesus’ body in laying there spread out on the floor. Peter arrives and runs right into the cave they had used as a tomb to bury Jesus. They examine the shroud, see the cloth used as a wrap around Jesus’ head folded and placed off to one side, and John, the text tells us, “believed,” even though they still didn’t understand how the Old Testament taught that the Messiah was to die and then be raised to life again.

Mary Magdalene had accompanied them back to the tomb, and after John and Peter went home, she remained outside the tomb, crying. As she cried, she bent over to look once again into the tomb, but this time found it occupied. Two angels, dressed in white were calmly sitting where Jesus’ body had been laid, one at the head and the other at the foot. “Why are you crying?” they asked her. “They have taken my Lord away,” she said, “and I don’t know where they have put him.” For some reason she turns back, and discovers a man is standing behind her. She figures he is the gardener, and he asks her the same question the angel asked. “Sir, if you have carried him away,” she replies, “tell me where you have put him, and I will get him.”

And then Jesus does something that should take our breath away. His body has been forever changed, scarred by the torture and bloody death he has experienced, and Mary through her tears cannot recognize him though she had followed him, believed in him, and loved him. I imagine there were a lot of ways in which Jesus could have revealed his identity to Mary, but he chose to do it in the warmest and most personal way imaginable. He said only one word, but it was all she needed to hear. He simply said her name, and in hearing that, she knew it was the Lord. Jesus told her she must not try to hold him to his earthly pilgrimage for a heavenly one now awaited him. Instead she was now a witness to the greatest event in all of history, the resurrection of the One who was God, had entered humankind, had embraced suffering and death, had overcome the grave, and who would now ascend to the Father bringing our humanity into the very Godhead itself. So Mary took the news to the rest of the disciples. “I have seen the Lord!” she told them (John 20:1-18).

Some scholars, attempting to explain the miraculous stories found in the New Testament, have suggested that these texts were inserted into the canon much later, by a church who wanted a certain view of Jesus upheld. As happens with many martyrs, people had come to think of Jesus as alive to them, so church leaders added the resurrection narrative to make the text adhere to what they were claiming was orthodox doctrine. There are numerous problems with this theory, but I’ll mention just one now because it involves the text I’ve been discussing. In the first century, the prevailing Roman and Jewish outlook was profoundly patriarchal—women were not even allowed to give evidence in a court of law. They were considered untrustworthy, witnesses whose testimony could not be believed. Yet in the resurrection narrative, the first witness Jesus appoints is a woman, Mary. This simple fact not only undercuts the notion that these were later additions to the text to get people to believe the resurrection, it reveals one way in which Jesus undercut the unjust perspective of a patriarchal perspective.

The story of the resurrection in the Scriptures reveals that God is not some far off deity, but is our Father. The apostolic message is that the one risen from the dead is both fully man and fully God, whose relationship with his people is personal. He is our elder brother, and he knows us by name. That Mary would recognize Jesus through her tears when he said her name is a reflection of this reality.

Perhaps Mary hadn’t looked at this man closely, since she assumed he was a gardener, a person best known for being in the background. Perhaps she was distracted by the two angels who were sitting a few feet away from her inside the tomb an experience I assume most people would find intensely distracting. Whatever the reason, she was now talking to Jesus without recognizing him, and what opened her eyes was his saying her name: “Mary.” It was the Lord. He was alive. He had been dead, most assuredly dead and buried, but here he was, alive. One word, but it was all she needed.

Someday, the Scriptures tell us, all of God’s people will appear before this one whose body is forever scarred by the whipping, the nails, and the spear they thrust into his side. His humanity is real and never sentimentalized. He will be enthroned as King of kings, and in consummating his kingdom righteousness will cover the earth like water covers the sea. He will be worshiped by all of creation, but always knows his people by name (John 10:3, Revelation 3:5).

“What matters supremely,” J. I. Packer says, “is not, in the last analysis, the fact that I know God, but the larger fact which underlies it—the fact that he knows me… I am never out of his mind… He knows me as a friend, one who loves me; and there is no moment when his eye is off me, or his attention distracted from me, and no moment, therefore, when his care falters… There is unspeakable comfort… in knowing that God is constantly taking knowledge of me in love, and watching over me for my good. There is tremendous relief in knowing that his love to me is utterly realistic, based at every point on prior knowledge of the worst about me, so that no discovery now can disillusion him about me, in the way I am so often disillusioned about myself… There is… great cause for humility in the thought that he sees all the twisted things about me that my [friends] do not see… and that he sees more corruption in me than that which I see in myself… There is, however, equally great incentive to worship and love God in the thought that, for some unfathomable reason, he wants me as his friend, and desires to be my friend, and has given his Son to die for me in order to realize this purpose.”

If you struggle with faith because you have unanswered questions, knowledge you desire in the hope it will make things certain, remember that what you know and don’t know is important, but not supremely so. There is a greater knowledge that does not depend on us, that embraces us within a greater love, and for which no doubt arises. That is the knowledge that truly matters.

Then, a week later, on the following Sunday, the disciples are together behind locked doors, afraid that the authorities that arranged for Jesus’ crucifixion might come after them. Then without warning Jesus is with them. “Shalom,” he tells them. “Know the peace that comes only from knowing me.” And he shows them his hands and his side—the scars of his crucifixion so they would know that there was no mistake that he was real, human, with a real body, and had really died and really rose to life again. He tells them he’s sending them out as his Father had sent him into the world, and then he breaths on them so they would receive the Holy Spirit. But Thomas wasn’t there, he had missed the meeting, and when the rest of the disciples told him what they had experienced, he expressed doubt. “Unless I see the nail marks in his hands and put my finger where the nails were, and put my hand into his side,” he told them, “I will not believe it.”

Another whole week goes by. Once again the disciples are together on Sunday, but this time Thomas is there. And once again, Jesus appears in the room with them. “Shalom,” he says again, “Be at peace.” And, then, wonder of wonders, he turns right to Thomas. “Put your finger here; see my hands. Reach out your hand and put it into my side. Stop doubting and believe.”

What’s interesting about all this, particularly in relationship to Thomas, is that a few chapters earlier we find him saying something that seems remarkably different and deeply courageous. It’s in John 11 in the story of another resurrection from the dead, this time of Jesus’ friend Lazarus who died and then was brought back to life by Jesus.

When the news of Lazarus’ death arrives, Jesus and his disciples aren’t in the province of Judea, where Lazarus lived, but were across the Jordan River in the area where John the baptizer had originally had his ministry. Jesus says they should go back to Judea, but the disciples aren’t so sure. “But Rabbi,’ they said, ‘a short time ago the Jews tried to stone you, and yet you are going back there?” (John 11:8) Whether they were concerned for Jesus, or simply scared for themselves, going back to the place where people wanted to stone you to death doesn’t seem like a good plan.

Jesus tells them that Lazarus is dead, and that it’s important he go and then out of all the disciples, Thomas speaks up. “Then Thomas (called Didymus),” John 11:16 records, “said to the rest of the disciples, ‘Let us also go, that we may die with him.’” Thomas was willing to follow Christ even into the face of danger, and told his friends that even if it meant death, they should be willing to follow Christ.

How is it possible for Thomas to be willing to die for Jesus and then later doubt the other disciples’ report of Jesus’ resurrection? On this the text of Scripture is silent, and so we must speculate with care.

One possibility that is sometimes mentioned is that his courage in chapter 11 is simply bravado, a bold front put on to look good in the eyes of his friends, his fellow disciples. I find that implausible, if for no other reason than it takes courage to reveal your doubts especially if you are the only doubter in the middle of a group of believers, and after the resurrection Thomas didn’t hesitate to let them know he had doubts that Jesus was alive. It seems more plausible that he showed the same courage in both texts.

Perhaps the answer to reconciling these two texts lies elsewhere. Full disclosure: the reason I think this is that the more I think about these texts, the more I identify with Thomas. In the story of the resurrection I am more like Thomas than I am any of the other characters who appear in the narrative.

I am certainly not like Mary, at the tomb so early that morning, 2000 years ago. I did not see the empty tomb, I did not run my hands over the huge stone that had been rolled from the entrance, I did not hear the angel’s question, and I did not hear Jesus say that one, tender word, her name that opened her eyes and caused her to see. I wasn’t there to run with John and Peter to the tomb, and I wasn’t there the following Sunday when Jesus appeared and showed the disciples the scars on his body. Like Thomas, I have to rely on the reports of others, and I have known, over time, both courage and doubt.

I identify with Thomas, because like him, I wasn’t there. But there is another reason why I identify with him. I find it easy to believe courageously when there is plenty of evidence of God’s grace and presence, but remarkably difficult to believe when things get out of control.

Sure it was risky to go back to Judea, but they were going back with Jesus. He was there, he was present, and so believing was easy and courage was within reach. But here after the resurrection, it’s different, and the difference makes all the difference in the world. For Thomas, at least, Jesus was no longer present, nothing seemed to make much sense—he had been killed, his enemies had won, the earth had plunged into sudden darkness, his lifeless body had been placed in a tomb, and Roman soldiers guarded the corpse. After so many miracles, after having Jesus there for three uninterrupted years, suddenly things had spiraled badly out of control. And at times like that, for some of us, at least, it is harder to believe. When God’s grace and presence seems clear, I find it easy to have a courageous faith, but when they are withdrawn, when things are closing in and getting darker, when all I have is indirect evidence, I find doubts appearing unbidden and strangely resistant to argument. Like Thomas, I have the witness of others who know the Lord’s grace, and I have the promise of the Lord’s word, but sometimes still I find it hard to trust and easier to doubt.

But notice—there’s more. Because even though Jesus rebukes Thomas for his lack of trust—“Stop doubting and believe”—it is a very gracious rebuke. Thomas insisted on more evidence than was necessary. He did not need to feel the scars on Jesus’ body because so many of his friends had seen Jesus that it made sense to believe he had risen from the dead. Thomas had good and sufficient reasons to believe in the resurrection, as we do. Still, Thomas’ doubts did not disqualify from being part of God’s people, nor did it get him erased from the list of the apostles. In the New Testament the apostles are seen as the foundation stones upon which the church is built (Ephesians 2:20-21)—and the good news is that one of those stones doubted, and not only still became part of the foundation, but the entire edifice didn’t crumble down as a result.

Jesus heard his doubt, and rather than dismissing it, responded to it, taking it seriously, as doubts and honest questions always should be treated. And indeed Thomas’ doubts were resolved. “My Lord and my God!” Thomas said, which was, and is, exactly right.

Some readers point out that not only did Thomas refuse to believe the witness of his friends to Christ’s resurrection, he wasn’t present when Jesus met with the disciples that first Sunday when Jesus showed them his hands and his side. We don’t know where Thomas was, or why he wasn’t there, but it’s easy to assume that Thomas was so discouraged by Jesus’ death that he stayed away on purpose. If so his doubts were his own fault, this line of reasoning goes, the result of poor choices. But the text doesn’t tell us that, so we really don’t know. He might have missed because he had the flu, or because the others neglected to tell him they were planning to meet. Who knows? The important thing is that Jesus doesn’t chide him for being absent, and neither should we. Even though his doubt might have been resolved had he been at the first meeting, Jesus still responded to his doubt with grace.

Occasionally there are believers who say they never experience doubt. Perhaps that is true, but I frankly find it very difficult to believe, not because I experience doubt but because of what the Scriptures teach about the life of faith. I suspect such believers either don’t have the courage to admit their doubts or do not reflect on their faith deeply enough to notice them. I can’t know for sure.

Still, I do know some things. I know there is a vital difference between being an unbeliever with doubts and being a believer with doubts. I know that doubts do not disqualify us from God’s family, and deserve to be addressed with grace and unhurried care. I know we do not earn God’s attention by being good at faith (whatever that would look like), but when by faith we trust the promises of God even while we know our knowledge is limited and always will be. And I know that in the end the knowledge that saves is his knowledge of us, not the other way around.

In The Screwtape Letters, C. S. Lewis imagined what advice a senior devil would give a younger devil who had been assigned to undermine the faith of a follower of Christ. In one of the letters that Screwtape, the senior devil, writes to Wormwood, the less experienced devil, he has Screwtape mention that troughs—those spiritual dry times, those periods in which God’s grace and presence seems absent—that these troughs are of great importance in a Christian’s life.

“We want cattle who can finally become food,” Screwtape says of Satan and his demonic hordes; “he [meaning Christ] wants servants who can finally become sons. We want to suck in, he wants to give out. We are empty and would like to be filled; he is full and flows over. Our war aim is a world in which Our Father Below has drawn all other beings into himself; the Enemy wants a world full of beings united to him but still distinct.

And that is where the troughs come in. You must have often wondered why the Enemy does not make more use of his power to be sensibly present to human souls in any degree he chooses and at any moment. But you now see that the Irresistible and the Indisputable are the two weapons which the very nature of his scheme forbids him to use. Merely to override a human will (as his felt presence in any but the faintest and most mitigated degree would certainly do) would be for him useless. He cannot ravish. He can only woo… Sooner or later he withdraws, if not in fact, at least from their conscious experience… It is during such trough periods, much more than during the peak periods, that it is growing into the sort of creature he wants it to be. Hence the prayers offered in the state of dryness are those which please him best. We can drag our patients along by continual tempting, because we design them only for the table, and the more their will is interfered with, the better. He cannot ‘tempt’ to virtue as we do to vice. He wants them to learn to walk and must therefore take away his hand; and if only the will to walk is really there he is pleased even with their stumbles. Do not be deceived, Wormwood. Our cause is never more in danger than when a human, no longer desiring, but still intending, to do our Enemy’s will, looks around upon a universe from which every trace of him seems to have vanished, and asks why he has been forsaken, and still obeys.”

Source

Material adapted from “Thomas” and “Thomas, Acts of” in Eerdmans Dictionary of the Bible edited by David Noel Freedman (2000).

The Gospel of John (II) by William Barclay (St Andrew Press; 1968).

The Acts of Thomas in the public domain online (http://www.earlychristianwritings.com/text/actsthomas.html). Packer from Knowing God (InterVarsity Press) p. 37.

The Screwtape Letters by C. S. Lewis (Time; 1961) p. 24-25.