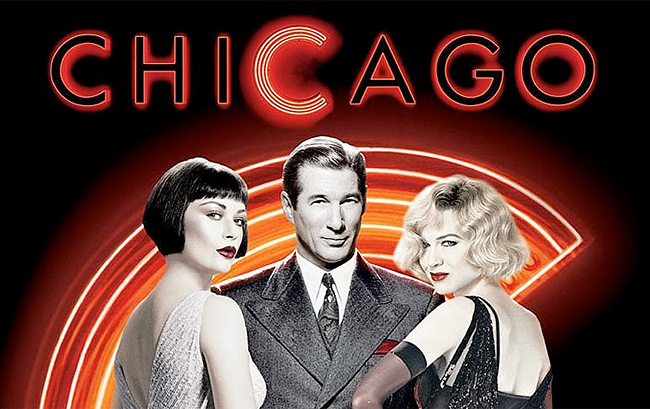

Chicago (Rob Marshall, 2002)

Judged by traditional values, criminals are objects of reproach and scorn. But judged by the values of entertainment, which is how the media now judge[s] everything, the perpetrator of a major, or even a minor but dramatic, crime, [is] as much a celebrity as any other human entertainer.

~Neal Gabler in Life the Movie

It’s all a circus, kid. This trial… the whole world… it’s all… show business!

~Billy Flynn in Chicago

Recently I received a letter in an envelope with no return address. Before reading it, I turned the letter over to see who had written. I could have read it cold, I suppose, waiting until the very end to discover who had sent it, but I never do that. Knowing who has written helps me read with more understanding and provides a sense of context which can change how I interpret what they wrote. After all, “Hey stupid!” can be either a warm greeting from a close friend, or the beginning of a migraine from the surly neighbor threatening to sue.

Watching a film with understanding includes a similar process: identifying the movie’s point of view (POV). Whether revealed explicitly or implicitly, every film has a POV, just as every letter has an author. In some films, for example, there is a narrator, as in American Beauty, an omniscient voice which explicitly establishes whose perspective reigns supreme. In some cases a character addresses the camera—and thus us—directly throughout the film, as in Wit. In other films the POV isn’t communicated by a narrator, but is revealed in the action, or in the movement of the camera. For example, the director can use repeated close-ups of a particular character so that we essentially see the action from their perspective, and thus interpret what’s going on in light of their response. However it is revealed, identifying the POV of a film deepens our understanding of the story, our appreciation of the film as art, and can keep us from misinterpreting the film’s message.

In the opening moments of Chicago, director Rob Marshall uses the camera to establish the film’s POV. Though it lasts only a few seconds on the screen, it is vital for understanding the film. In case we missed it, Marshall uses some other cinematic techniques throughout the movie to remind us of what he established in those opening moments. (A good thing, apparently. Of all the people I’ve asked to describe the opening moments of the film only one mentioned the POV shot.) Even if Chicago’s sets, costumes, and action were not so stylized, signaling the realm of the imagination, the POV shots tell us that we are seeing things not “as they are,” but through the eyes of Roxie Hart, played by Renée Zellweger. And since Roxie’s values are entirely defined by the demands of celebrity and the glitter of show business, all that transpires is filtered through her consciousness. It is as if the director is saying, “Imagine with me what life would look like if the horizons of reality are bounded by the values of show business. Imagine what society would be like if the judicial system, the news media, and even relationships were defined not by truth, law, love, and commitment, but were instead reduced to merely another form of entertainment.”

Sadly, that is not so hard to imagine in our fallen world. And Chicago reveals that it would look sad beyond imagining.

Chicago burst noisily into our cultural consciousness, elbowing into conversations even of people who didn’t see it. Being nominated for 13 Academy Awards and winning 6 (including Best Picture) helped of course, as did the advertising blitz that accompanied its release. As did the high energy of its song and dance numbers, its glittering sensuality, and the high quality of the production. A person would have to be tone-deaf not to tap their toes as they watch. Good musicals are rare, and Chicago is a superbly crafted one, laced with a highly charged irony which appeals to our cynical age.

There is another reason for Chicago’s impact, however, which explains I think both why the film receives so much attention, and why it deserves it. At a time of economic, spiritual, and moral uncertainty, Chicago taps into the dis-ease felt by many—the fear that there is a great deal of rot eating away at the heart of our world, but the film exposes the rot with irony rather than with a scolding. We are tired of reading news reports about lawyers using courtroom antics in the miscarriage of justice. In Chicago we meet Billy Flynn, an utterly corrupt attorney, but in place of a drama that deepens our despair, we are allowed to smile, sadly, as he tap dances in the court room, manipulating the evidence to win the case, freeing an obviously guilty murderer. We are weary of a media we don’t fully trust, but in place of one more solemn editorial on media bias, we can’t help but laugh, sadly, when the press in Chicago are transformed into marionettes, dancing dangling at the end of strings. Chicago sweeps us up in bright songs, highly energetic dance numbers, and gorgeous, stylized sets designed to overload the senses. It entertains, but then when we least expect it, reveals how life is far richer than mere entertainment by telling us the story of a woman for whom entertainment is all there is. Swept up into her world, we share her point of view and see the rot in the media, the judicial system, in covenant-less relationships, even in show business itself.

Chicago is effective as social commentary because rather than rubbing our faces in the problem, it seduces us with a bright musical to reveal the shallowness and depravity of a society in which celebrity trumps everything. There is only one character in Chicago who borders on true goodness, and that is Amos, Roxie’s big-hearted lug of a husband, played to perfection by John Reilly. From Roxie’s point of view, however, he is there merely to be used and then discarded. In what has to be one of the saddest numbers in musical history, Amos sings and dances through “Mr. Cellophane,” in which he recognizes his invisibility in a world defined by celebrity, glitz, social power, and the applause of show-biz success. When the song is finished, Amos, dressed as a clown, quietly backs off stage and out of sight. “Hope I didn’t take up too much of your time,” he says.

In our postmodern world the values of entertainment infiltrate every part of life, in ways we are only partially aware. Even those Christians who react most negatively, pulling back into carefully constructed ghettos to live for safety and personal peace are, ironically, allowing the world of entertainment to mold their lives and families. They end up being shaped more by their sense of offense than by the gospel. We are not untouched by the culture of which we are a part. Our goal must be sanctification, not seclusion, for only then is faithfulness possible.

Chicago tells the bad news, and in terms an unchurched world can understand. Adopt the wrong values—Roxie’s values—it tells us, and things fall apart. Adopt an insufficient world view and even murder becomes nothing more than a self-serving ticket to success. And when the values of celebrity, power, and entertainment replace virtue and begin to shape the institutions of civilization, truth is jettisoned, love becomes coupling, and justice is perverted.

“Chicago’s simple, smart idea,” writes a British film critic, “is that celebrity trumps even sex and money, and the cuts by Marshall and screenwriter Bill Condon whittle down this cool take on American drive even further. Characters are reduced to limelight-seeking missiles: as she prepares to give evidence at Roxie’s trial, Velma clears her throat and apologizes ‘I haven’t worked for a while.’ Roxie is menaced by the prospect of a shrinking spotlight: a terror as great as death is that of falling so low even ‘J. Edgar Hoover couldn’t find your name in the papers.’”

In The Gravedigger File, Os Guinness reminds us that the Scriptures define sin both as rebellion against God, and as folly. Pre-evangelism thus is often best done not with an intensely serious sermon, but with the smile of the fool-maker who uses gentle wit or biting satire to reveal truth that people would prefer to ignore. This is part of the enduring appeal of G. K. Chesterton, who evokes smiles while wielding the scalpel of truth. This is the way of the “jester, building up expectations in one direction, he shatters them with his punch line, reversing the original meaning and revealing an entirely different one… he turns the tables on the tyranny of names and labels and strikes subversively for freedom and for truth.”

The church needs such jesters, fool-makers for Christ who can strike a blow against the emptiness of worldly values while inviting their audience to hum along to the melody of their revelatory song. Jesters like the prophet Nathan, who confronted David not by accusing him of adultery and murder, but by telling a story that drew David in and when he least expected it, laid bare his guilt (2 Samuel 12). It’s too bad, in other words, that Christians aren’t producing films like Chicago. In the meantime, we can enter into the conversation Chicago is provoking.

“Who then is wise enough for this moment in history?” Guinness asks. “The one who has always been wise enough to play the fool. For when the wise are foolish, the wealthy poor and the godly worldly, it takes a special folly to subvert such foolishness, a special wit to teach true wisdom.”