Books / Culture / Maturity and Flourishing

Character v. Personality

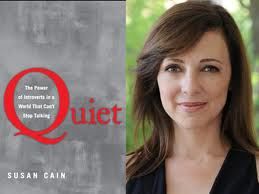

As Susan Cain points out in her fascinating book, Quiet, American society went through an important cultural shift in the opening years of the 20th century. It was one of those shifts that effected every person, even those who were unaware it had occurred or who took pride in being aloof from such things. Historian Warren Susman referred to it as a shift from a Culture of Character to a Culture of Personality.

“In the Culture of Character,” Cain notes, “the ideal self was serious, disciplined, and honorable. What counted was not so much the impression one made in public as how one behaved in private… But when they embraced the Culture of Personality, Americans started to focus on how others perceived them. They became captivated by people who were bold and entertaining.”

There are a number of reasons why this shift occurred. Changing demographics meant more people lived in cities surrounded by strangers. Gone was the day when people grew up around neighbors who were acquainted with one another for a lifetime. People competed for jobs in a mobile world and now how you came across in an interview was as important as your experience, skills, and education. Now to make friends or land a job the first impression you made became more strategic than virtues you had quietly nurtured over decades. In the fast paced world of modernity one had only seconds to stand out from the crowd, and what others thought of you in that instant could open and close opportunities.

The world of advertising followed the shift. A 1922 ad for Woodbury’s soap warned, “All around you people are judging you silently,” and the Williams Shaving Cream Company claimed, “Critical eyes are sizing you up right now.” Using their products, it was claimed, would add to a person’s appeal at a time when instant impressions counted far more than it ever had before the explosive impact of the industrial revolution.

Americans have always loved self-help books and the popular manuals selling at the time tracked the shift that was taking place. Character: The Grandest Thing in the World by Orison Swett Marden was published in 1899; in 1921 the same author produced Masterful Personality. It was not simply a change in vocabulary, as if personality was another word for character. “Susman counted the words that appeared most frequently,” Cain says, “in the personality-driven advice manuals of the early twentieth century and compared them to the character guides of the nineteenth century.” The two lists are instructive and revealing.

The most frequently used words in the self-help manuals from the 19th century Culture of Character:

Citizenship

Duty

Work

Golden deeds

Honor

Reputation

Morals

Manners

Integrity

And here are the most frequently appearing words in the self-help manuals of the early 20th century Culture of Personality:

Magnetic

Fascinating

Stunning

Attractive

Glowing

Dominant

Forceful

Energetic

It is hardly a coincidence, Cain notes, that the burgeoning Culture of Personality spawned an obsession with movie stars.

It is true that what I have related here is a story from the past. A full century has passed since this cultural shift overtook beliefs and values that Americans had tended to assume were essential to human relationships, personhood, and community. Yet, if anything the Culture of Personality is not only with us still, technology and the new social networking tools of the internet have provided us with novel opportunities to further shape the way we present ourselves to others.

All of which suggests a number of questions that discerning Christians will want to reflect on and discuss thoughtfully.

Questions

1. To what extent do you believe we are still in a Culture of Personality? Why?2. Some in the church might argue that unlike the rest of the world, true Christians care more for character than for personality. Do you agree? Why or why not? They might argue, further, that the proof of this is found in the wholesome character displayed by home-schooled or Christian-schooled children in contrast to the young people being produced by the public schools. How would you respond to this idea?

3. In his epistle to the Christians living in Galatia, St. Paul composed a list that has become famous even outside church circles that he identifies as the fruit of God’s Holy Spirit in the believer’s life (5:22-23): Love Joy Peace Patience Kindness Goodness Faithfulness Gentleness Self-control Eugene Peterson, in his paraphrase of Scripture, The Message, translates the apostle’s list this way: “He brings gifts into our lives, much the same way that fruit appears in an orchard—things like affection for others, exuberance about life, serenity. We develop a willingness to stick with things, a sense of compassion in the heart, and a conviction that a basic holiness permeates things and people. We find ourselves involved in loyal commitments, not needing to force our way in life, able to marshal and direct our energies wisely.” Compare and contrast this biblical list with the two lists in this article culled from the self-help books of the Culture of Character and the Culture of Personality.

4. Some Christians would point to two texts of Scripture to prove that Christians must simply reject the Culture of Personality in favor of a Culture of Character. The first is from the Old Testament where the prophet Samuel is sent by God to anoint the next king of Israel. “The Lord said to Samuel, ‘Do not look on his appearance or on the height of his stature, because I have rejected him. For the Lord sees not as man sees: man looks on the outward appearance, but the Lord looks on the heart’” (1 Samuel 16:7-8). The second text is written by St. Paul in a passage where he defends his authority as an apostle since opponents have argued that he is not worthy of such deference: “We are not commending ourselves to you again but giving you cause to boast about us, so that you may be able to answer those who boast about outward appearance and not about what is in the heart” (2 Corinthians 5:12). Both biblical texts, it can be argued, claim a specific preference for the values of the Culture of Character over those of the Culture of Personality. How would you respond?

5. Since we are Christians who value righteousness, virtue, and sterling character who yet live in a world in which first impressions do matter (for jobs, beginning relationships, receiving a hearing, and so much more), is it possible to have sympathy for both Cultures? Is the best response to this cultural dichotomy simply to excel at both? Why or why not? To what extent do you think the three lists are mutually exclusive?

6. What do the priorities and values of a Culture of Personality do to the attractiveness of the Christian gospel? What incorrect strategies might believers use to overcome this barrier? Why are they incorrect? What correct strategies would be wise to consider?

7. Review the biblical texts that describe the attributes of church officers, the elders and deacons that are raised up by God to shepherd his people (Titus 1:5-9; 1 Timothy 3:1-13). How might living in a Culture of Personality bring subtle changes to how these qualifications are understood and identified?

8. The list that identifies the primary traits of the Culture of Personality tends to favor extroverts over introverts. What does this do to extroverts and to introverts? What will be lost in the process—in the culture, in the workplace, and in the church?