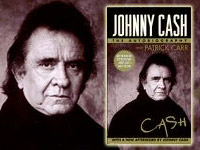

CASH: The Autobiography (Johnny Cash with Patrick Carr, 1997 )

There is something fine about grace. Just when I think I have it figured out, I am shown that I can no more capture it than I can hold in my hands a breeze moving through a stand of aspens. I especially like the way it punctures my cynicism, revealing how little I actually believe in the power of grace even though I loudly profess otherwise. Just when I think our culture is so deeply celebrity-drunk that no person of substance can make a difference without being eaten alive, the rich legacy of Johnny Cash reveals otherwise.

Johnny Cash’s life and work reveals grace not primarily because he was fond of gospel music, but because his life, revealed in his work, was a testimony to grace. Not because one of his final albums was My Mother’s Hymn Book, but because he can be explained in no other way. Cash understood pain, addiction, the breakup of marriage, failure, and great loss. His brother Jack’s death (for which their father blamed Johnny) when Johnny was 12, was a blow that went to the depths of his soul. He never hid these sorrows but faced them, and with his beloved wife, June Carter, had the grace to face them down.

There were nights I don’t remember

And there’s pain that I’ve forgotten

Other things I choose not to recall

There are faces that come to me

In my darkest secret memory

Faces that I wish would not come back at all

In my dreams parade of lovers

From the other times and places

There’s not one that matters now, no matter who

I’m just thankful for the journey

And that I’ve survived the battles

And that my spoils of victory are you

Johnny Cash was born in 1932, but was named J. R. by his parents because they couldn’t agree whether to name him John or Ray. When he was 12, as the congregation sang the old hymn “Just as I Am,” he went forward in the First Baptist Church of Dryness, Arkansas, to pray to receive Christ as his Savior. When he entered the Air Force at age 18, more than initials were required for military paperwork, so he signed himself John Ray Cash. In 1955, after his stint in the service, he recorded “You’re Gonna Cry, Cry, Cry,” deciding “Johnny Cash” looked better on the label. Two years later he was introduced to amphetamines by physicians who were happy to prescribe the new miracle drugs to truck drivers and artists who needed to stay awake on the road. In 1959 Cash gave a concert at San Quentin prison, where Merle Haggard was in the audience. “He captured the entire prison,” Haggard recalls. “I don’t think there was a guy in the entire joint who didn’t like Johnny Cash when that show was over.” A decade later Cash returned to San Quentin and recorded one of the finest albums of his career.

Cash proposed to June Carter on stage in London, and they were married in 1968, a month before Martin Luther King was assassinated. They were deeply in love, a love that never wavered in commitment even in the dark days of addiction, recovery, and failure that were yet to come. In subsequent years Cash had a weekly television show, starred in (largely forgettable) movies, and befriended Billy and Ruth Graham, appearing as a guest at several of Graham’s crusades. In 1980 Cash was inducted into the Country Music Hall of Fame, and a year later was attacked by an ostrich on his ranch, which broke several ribs and tore open his abdomen. In 1983 his family intervened, taking him to the Betty Ford Center to deal with his continuing struggles with addiction.

In 1993 he recorded “The Wanderer,” in Dub-lin with U2, which was released on their album, Zooropa. In 1997 he published Cash: The Autobiography, which is worth reading for its honesty, plain speech, and heart-felt celebration of grace in the midst of a broken, pain-filled life. It is a story told simply and with deep gratitude. In 2003, June Carter Cash was hospitalized, and then died. On May 18, family, musicians, and a multitude of friends and admirers gathered for her funeral, and on September 12, 2003, Johnny followed her to the promised land they had often sung about together. A few weeks before his death, Cash was awarded an MTV award for his video “Hurt,” a song originally by Nine-Inch Nails, but made his own in the way only Johnny Cash could accomplish. Bono says “it’s perhaps the best video ever made.” Emmylou Harris says the video “puts all those bare-navel, soft-porn videos to shame. It shows videos can actually have a profound effect on us, and it took Johnny Cash to once again show that. It’s come full circle, because when he first came on the scene with that power, he was all that rock & roll could be.”

I will let you down

I will make you hurt

If I could start again

A million miles away

I would keep myself

I would find a way

When I hear that someone famous has died, I receive the news more as a sound bite than as something which moves me. But when I heard that Johnny Cash had died, I grieved, and considered wearing a black armband. The music world had lost a legend, America had lost a great man, and the church had lost a saint.

I am not capable of adequately summarizing Cash’s legacy, but to my mind, at least, it includes a number of lessons we forget to our peril:

The effects of gifts can exceed what we ordinarily expect. “As with many legends in popular music,” Steve Turner writes in The Man Called Cash, “it’s not easy to say exactly what made Cash great. He never became a great guitarist, his voice had a limited range, and his lyrics veered between poetry and doggerel. But the combination of that voice, those words, and that guitar far exceeded the greatness of any one element. He was a presence, a form of energy, a vehicle for truth.”

I wonder why it is so easy to forget how a true gift, faithfully used, can transcend what we would imagine or expect. Perhaps we’re so programmed to equate success with extraordinary things we forget that good can come from simple things. When we love someone enough, for example, to give them the gift of unhurried time. Or what happens when we simply listen to someone, and walk beside them after they have disappointed themselves, and us. We forget that greatness has less to do with the spectacular than it does with compassionately and faithfully using whatever gifts we have, no matter how ordinary they seem to be.

Johnny Cash can be criticized as a musician on all sorts of grounds, but those insights, no matter how learned, are meaningless if they dismiss him. “I think we can have recollections of him,” Bob Dylan says of Cash, “but we can’t define him any more than we can define a fountain of truth, light, and beauty. If we want to know what it means to be mortal, we need look no further than the Man in Black. Blessed with a profound imagination, he used the gift to express all the various lost causes of the human soul. This is a miraculous and humbling thing.”

Authenticity matters. Johnny Cash was simply himself, clay feet and all, and had such a deep confidence in grace that he felt no need to hide. “He wrote of sin, not as it affected other people, but as something with which he’d become intimately acquainted,” Turner notes. “Cash was fond of saying that the only reason he didn’t carry a burden of guilt for his errors was because he figured that, if God had forgiven him, the least he could do was to forgive himself.”

It is true that he was an imposing man physically, but the authenticity with which he lived his life had a far greater impact than his size or famous growl when someone crossed him. Bono recalls a time when he visited the Cash home, and June Carter prepared dinner. They sat down, and Cash asked them all to bow their heads, and then “said the most beautiful, poetic grace.” After saying amen, Cash said to Bono, “Sure miss the drugs, though.” The moment impressed Bono. “He just couldn’t be self-righteous,” Bono says. “I think he was a very godly man, but you had the sense that he had spent his time in the desert. And that just made you like him more.”

Christianity is not made more attractive by being sentimentalized. Nor does a life of faith mean that problems will evaporate, doubts will vanish, and that all our kids will grow up in ways we prefer. Authenticity is attractive because it is real, and because grace is meaningless unless it heals what is truly broken.

Stories are worth hearing. Not many of us will write a biography, and that is as it should be. Every one has a story worth telling, however, if for no other reason than it is only in telling it that we see how it relates to The Story of what God is doing in history.

Cash: The Autobiography is a lovely book, and a story we need to read. It’s simply told, and as I read I had the impression Cash was sitting beside me, talking. It’s the sort of book I’d happily give to either Christians or non-Christians.

Steve Turner, author of Amazing Grace: The Story of America’s Most Beloved Song, was given permission by Johnny Cash to write an authorized biography. Sadly, Cash died just before they were to begin working on it together. Cash’s family and friends cooperated with Turner, and The Man Called Cash: The Life, Love, and Faith of an American Legend is a wonderful book. It is especially significant that Turner shares Cash’s faith, and like Cash, is able to speak of it in a fresh, natural way without being “religious.”

Little things count. One of the tributes to him included in the book published by the editors of Rolling Stone is by Mark Romanek. He worked as director on the video “Hurt” which Cash made just prior to his death. Romanek mentions that Cash was moved by the song because he had lost friends to addiction and had struggled with it himself. He notes how obviously in love Johnny and June Carter were, since they were both in the studio as the video was being filmed. And then he mentions a small detail. “Johnny was also extremely generous,” Romanek says, “he autographed about thirty-five vinyl copies of The Man Comes Around as a parting gift to the crew, who were in awe. That had never been done by any of the forty artists I’ve worked with.”

Great music is powerful. I cannot imagine what it is like being an inmate in a prison like San Quentin, but listening to Johnny Cash at San Quentin still transports me out of the narrow horizons of my life. Cash’s song, “A Boy Named Sue,” always struck me as rather silly, but when he sings it here to the cheers of the inmates, the lyrics suddenly take on added significance. And when he includes the old hymn “There’ll be Peace in the Valley,” he doesn’t have to preach to make it clear that he believes hope in such a place is found in Jesus Christ. “He brought Jesus Christ into the picture,” Merle Haggard says, “and he introduced Him in a way that the tough, hardened, hard-core convict wasn’t embarrassed to listen. He didn’t point no fingers; he knew just how to do it.”

Some of the hymns on My Mother’s Hymn Book aren’t favorites of mine. A few are too sentimental for my taste, shaped by revivalist and pietist tendencies in American evangelical Christianity. Still, I like them when Johnny Cash sings them. They fit his life and his faith, and he sings them in a voice grown old, but with an unmistakable authenticity. This is a man who does not simply sing about grace, he believes in grace and has been shaped by it.

We will not understand Christian faith, nor engage our postmodern world with the gospel unless we embrace beauty with the same passion with which we embrace truth. Music is not just entertainment, but essential to life. Even if you don’t like the music of Johnny Cash, listening to it with ears that hear will help you get just how essential it is.

“Cash encouraged people to be honest, to have integrity, to fearlessly explore within, to be compassionate, and to search for truth,” Turner concludes. “The realm Johnny Cash lived in was clouded by pain and colored by grace. He had the ability to transform the rough and commonplace into objects fit for heaven, just as he had been transformed.”

We walked troubles brooding wind swept hills

And we loved and we laughed the pain away

At the end of the journey

When our last song is sung

Will you meet me in heaven someday?