Discernment / Scripture / Spirituality

The Birth of the Christian Worldview

Imagine a citizen of Rome thinking about the world the year Herod Antipas became tetrarch of Galilee—4 bc, the historians reckon. There are skirmishes at the far reaches of the Empire, but no one seriously thinks the Roman Legions will not be able to keep the peace and ensure security. The roads remain well maintained and guarded. Commerce flows within the Empire and beyond. Roman culture, inherited from the Greeks is a respected and rich tradition of religion, philosophy, science and rhetoric that has birthed an outflowing of poetry, engineering, art and belief. Overall things seem certain, and life by and large is satisfying. It is impossible to imagine the world without Rome.

If our Roman thought about the minor province of Judea at all, it would not include the idea that a wandering teacher from a place called Nazareth would soon be born, work miracles and be crucified as a criminal. And anyone imagining that would not have thought that this one’s followers would over the next several centuries give rise to a distinctly unique, life giving and world transforming worldview.

Yet it happened. The story of the birth and development of that worldview should be better known, especially by those who today name the crucified one as Lord.

The ones responsible lived in the four centuries after the apostles, known as the Patristic period. Most of us have heard some of the names involved: Ignatius (35-108), Polycarp (69-155), Justin Martyr (100-165), Tertullian (160-225), Origen (185-254), Athanasius (296-373), and Augustine (354-430). The church grew explosively, going from a tiny persecuted sect to the official religion of the Roman Empire. It also faced challenges from without and within. Jewish and pagan thinkers wrote works seeking to discredit and disprove Christian belief and practice, and important doctrinal issues needed to be defined according to the tradition of teaching handed down by the apostles.

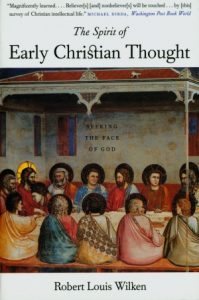

The Patristic thinkers were highly educated, sophisticated and philosophically astute. The standards of rhetoric and reason honed by their Greek and Roman contemporaries were readily apparent in their work. But then, Robert Louis Wilken says in The Spirit of Early Christian Thought, they read the scriptures.

The Bible formed Christians into a people and gave them a language.

As intellectuals formed by the classical tradition, the first Christian thinkers belonged to a learned and contented club, secure in the confidence they knew whatever was useful to know. In school they had memorized long passages from Homer or Virgil, and by imitating the elegant sentences of Isocrates or Cicero they had learned to write graceful prose and speak with polished diction. Before reading Genesis they had read Plato, before reading the prophets they had read Euripides, before reading the books of Samuel and Kings they had read Herodotus and Thucydides, and before reading the gospels they had read Plutarch’s Lives. Intensely proud of their ancient culture, they took pleasure in the beauty of its language, the refinement of its literature, and the subtlety of its sages.

Yet when they took the Bible in hand they were overwhelmed. It came upon them like a torrent leaping down the side of a mountain. Once they got beyond its plain style they sensed they had entered a new and mysterious world more alluring than anything they had known before [pp. 52-53]

In The Spirit of Early Christian Thought Wilken summarizes for lay readers the process by which the Patristic thinkers gave birth to a distinctly Christian perspective on life and reality. “Christian thinking,” Wilken argues, “while working within patterns of thought and conceptions rooted in Greco-Roman culture, transformed them so profoundly that in the end something quite new came into being” [p. xvii]. He introduces us to the characters involved, explores their work and helps us see the impact their thinking had on the culture of their day and on the church, giving birth to art, poetry, worship, spirituality, ethics, and learning.

Christians who do not know their rich cultural heritage need to read this book.