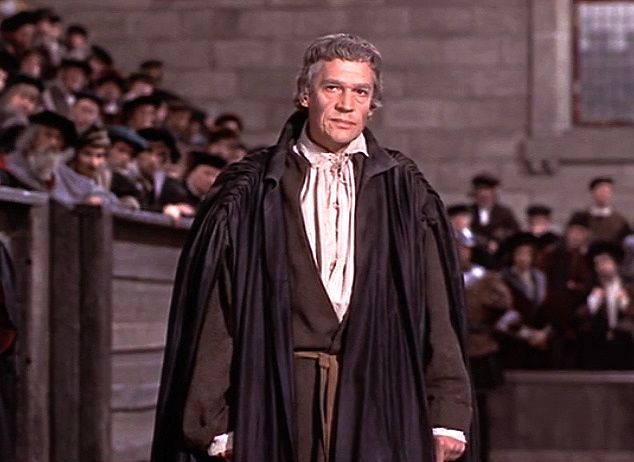

A Man For All Seasons (Fred Zinnemann, 1966)

Is anything worth dying for?

A few years ago I was part of a weekend film festival in England sponsored by the British branch of L’Abri. I have lots of memories from that weekend, but the one that comes most quickly to mind is how cold it was. Being a Minnesotan I know something about cold. I have stood outdoors in the country in the northern part of the state, near the border with Canada, when the temperature is well below zero, watching the Aurora Borealis sweep across the sky. I have stayed at a remote cabin on the shore of a lake in early winter as the temperature dropped, listening to the deep booms and sharp cracks as the water of the lake froze. I have thrown a glass of water into air so frigid it instantly burst into a cloud of steam and crystals and not a single drop of liquid hit the ground. I have driven my car after a night of temperatures so low that for the first several blocks I could hear and feel the thumping of the tires turning past the flattened side that had rested against the frozen ground. Still, that weekend in Great Britain felt colder than anything I have ever experienced at home. It drizzled constantly outside, and so the damp—oh, so very damp—seeped into my toes and fingers, so that even rooms with a blazing fireplace seemed chilled. Only the lovely warmth of community and unhurried conversation, with endless cups of hot tea, made us forget the cold.

The film festival was a delightful time, a weekend of art, story, and discussion about the perennial questions that every generation raises in one form or another. I had helped choose the films, and we had decided that one should be a classic, a movie that had been so well crafted that it was good enough to stand the test of time. The film we chose for that category was A Man for All Seasons (1966). What we did not expect was that of all the films we watched and discussed, this was the film that seemed to resonate most deeply in the hearts and imaginations of the participants. One man, a student from Korea (if memory serves correctly) wept as he watched. When the film ended there was a profound silence in the room, and once the discussion began it was hard to bring it to an end. Though a very well made and compelling film, it is also dated, but that does not detract from the power of the story.

The story line in A Man for All Seasons is deceptively simple. Henry VIII was king of England. He wanted a divorce because his wife had failed to provide a son and because he had found a lover. Since the pope will not grant his blessing for such a marital travesty, the king decided to leave the Church of Rome, be declared the head of the church in England, and this way be allowed to take his mistress for his wife. Today, when churches proliferate for reasons far less impressive, this may not seem to be a very big deal. But in 16th century Europe, religious belief, the church, the sanctity of marriage, and royal behavior—indeed, the possibility of virtue and vice—were viewed as having true significance for this life, and for the next. So, King Henry asked his nobles to sign The Act of Supremacy and they did so, because Henry was not a king that took disagreement lightly. One man, Sir Thomas More, however, the king’s chancellor, would not sign because his conscience would not allow him to do so. The Duke of Norfolk, a friend who had signed, pleaded with More. “Oh confound all this,” The Duke said. “I’m not a scholar, I don’t know whether the marriage was lawful or not but dammit, Thomas, look at these names! Why can’t you do as I did and come with us, for fellowship!” “And when we die,” More responded, “and you are sent to heaven for doing your conscience, and I am sent to hell for not doing mine, will you come with me, for fellowship?” Thomas More resigned his position, but Henry was not content. More was widely famous for his integrity, known to be a man of principle who could not be bribed and who had always refused even the appearance of corruption. Though now he was merely a private citizen of the realm, More’s refusal to sign seemed like a trumpet blast against the legal slight of hand the royal court had embarked upon. More was arrested, tried for treason, and beheaded. To the very end he chose principle over politics, virtue over convenience, conscience over pragmatism.

Though it is a simple story, it is not a simplistic plot. A Man for All Seasons has a richly developed script in which personal identity and integrity are explored in a setting where one man, standing for what he believes, is convinced that death is preferable to losing his soul. “It is a literate, humane treatment of the dilemma an honest man faces,” Roger Ebert says, “in a corrupt society.” The film is historically quite accurate, except for two details worth noting. First, More was not the only man to refuse to sign and to lose his head as a result. Though this does not mean that More’s stand was not heroic or lonely, the film can be seen to imply he may have been alone in his stand. The second fact worth noting is that while in political power More persecuted heretics (read: Protestants and non-conformists), condemning them to death. I do not mention this to detract from More’s integrity, since even here he was following what he passionately believed to be true. I mention it to note the political turmoil of the day, and how the death penalty was used in Europe at the time in instances that today we would find intolerable.

A Man for All Seasons explores categories of thought and reality that get to the very heart of what it means to be human. Knowledge is not mere data, neutral bits of information that we can amass or reject depending on how we are feeling at the moment. Knowledge arrives with responsibility and when we refuse to acknowledge that we have assumed a stance that is slightly less than fully human.

A Man for All Seasons is one of those rare pieces of art that though clearly dated, remains timeless. It remains timeless, first, by being a superb example of cinematic art. And it remains timeless by raising questions that we must all face—questions of conscience, authority, integrity, law, and love. If I violate my conscience for the sake of convenience, what have I lost? Am I known as someone whose word is inviolate? To what extent is my personal integrity worth suffering loss? And do I believe anything, love anything that is truly worth living, and if necessary, worth dying for?