A Blast of Ethics to the Face: The “Secular Lament” of Propagandhi’s Victory Lap

Consider the world of Ecclesiastes: it is a place of destruction, malaise, repetition, and despair “under the sun,” where even the beauty you see is stained with the bittersweet reality that the clock is ticking slowly toward death. It’s a challenging vision, even for Christians. Now imagine this same world, with one difference: there is no divine presence to offer respite from the sun’s withering gaze. What emotions would come to the surface in such a world? Anger and frustration, without question. What type of music would capture the essence of despair? Punk rock, most likely.

Enter Propagandhi, one of Canada’s premier punk bands. For over 25 years, Propagandhi has paired blazing punk riffs with searing social commentary, and their musical caliber and moral voice have only ripened with age. Their seventh album, 2017’s Victory Lap, perfectly demonstrates their musical chops and ethical vision, making it an important piece for Christians to digest. If we take the doctrine of common grace to be those places where the walls are thin between the world and God’s redemptive activity, Victory Lap serves to shake Christians out of some of our cultural captivity and offers a possible bridge for socially-conscious punk rockers to eventually hear the message of Christ.

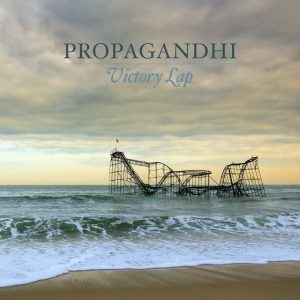

Victory Lap engages a wide range of issues, such as police violence, the #MeToo movement, sexism, and animal rights. Less of a sniper rifle and more of a shotgun blast, Propagandhi targets a whole range of 21st century problems. If the album has an overarching theme, its cover art is suggestive; with a rollercoaster sinking into the ocean, “victory lap” becomes the ironic descriptor of a culture in its last throes, partying while the tide rises.

From the opening lines, visions of death loom large, as does the band’s rage:

When the flames engulfed

the home of the brave

the stampede toward the border was in vain.

Faces palmed, faces pale

as the wall they said would make them great could not be scaled.

When the free-market

fundamentalist steps on a roadside bomb outside Kandahar

bleeding to death,

I swear to Ayn Rand

I’ll ask if he needs an invisible hand.

(“Victory Lap”)

There is a fatalistic sense of doom here; despair is inevitable, from the futility of People of Color to escape the violence of White supremacy, Comply? Resist? / No difference. / Resist? Comply? / You die. (“Comply/Resist”), to the inability of activists to make any lasting change in society, Damned if we don’t. Damned if we do. / I’d just shut my mouth if I were you. (“Letters to a Young Anus”), to the inability of anyone to escape their eventual death, Our lives lead to nowhere, we’re counting time. / Then grasping for each other, as we’re crushed beneath the tide. (“Nigredo”). You’re nothing but the bottom of some far future latrine / my little libertine. / That’s your universe in a nutshell. (“Call before You Dig”).

The inevitability of suffering is amplified by a sense of ironic backfiring: the things meant to theoretically help society end up destroying society. America’s hoped-for wall on the southern border becomes its cage of death (“Victory Lap”). Victorious soldiers who fought for freedom are ensnared by their involvement in war (“Failed Imagineer”). The “enrichment programs implemented to extend our captive lifespans” turn out to be nothing more than “longer chains” (“Adventures in Zoochosis”). Our best efforts backfire in our faces; fate mocks us, then dishes up more suffering.

Propagandhi does recognize a sense of beauty in the world, but these glimpses of beauty only make the tragedy of human life more painful. The colossal waste of energy / talent upon the talented / freedom upon the free. / This whole damn beautiful life wasted on you and me. (“Victory Lap”).

As much as beauty tragically emphasizes our human misery, it does serve a more hopeful purpose: to undermine the status quo. In the animal-rights song “Lower Order (A Good Laugh),” Chris Hannah, the lead singer and songwriter, recounts the aftermath of his first hunting trip as a young boy: They laughed as I cried / and stroked his blood-soaked iridescent quills. A trip intended to be a rite of passage becomes the inception of a life-long commitment to animal rights; beauty undermined the status quo. Likewise, on “Cop Just Out of Frame”:

They say that Quang Duc’s heart survived the flames unscarred.

A righteous calling card left upon the palace gates

for the invertebrates, their grip on power pried apart

by just one frail human being.

No weapon, no war machine.

Another unexpected reversal, the beauty of the self-sacrificial act upending corruption. Propagandhi’s music might implicitly bear the hope of beauty to bring change; musically, the album vacillates between the fast and loud and melodic and lovely. Both sonically and lyrically, beauty and brokenness vie for supremacy on this album.

Adding to human devastation is Hannah’s observation about humanity: no one is innocent, including him. As much as he has ranted about systemic evils, he is often a complicit bystander, and even participant. In “Cop Just Out of Frame,” Hannah risks contemplating a dramatic act of self-sacrifice in the style of Vietnam’s Quang Duc, the Buddhist monk who famously committed suicide as a political protest in 1963: If I thought it would help I would immolate myself / in full view of the camera crews. He initially dismisses this idea, because like so many efforts, it too might backfire: But as we all know the only tale that would be told / would be that it was me, not them, who was insane. Yet instead of blaming society for their idiocy, he takes a surprising turn of introspection:

But who the fuck do I think I am fooling?

As if I know the first thing of sacrifice or selflessness.

I’m the cop just out of frame, who at the first sight of the flames,

throws himself prostrate to the ground in reverence.

Some accounts of Quang Duc’s self-immolation include stunned passersby, even some police, throwing themselves to the ground in awed recognition of this sacrificial act. Such police were agents of the regime that Quang Duc protested, placed there to maintain an oppressive status quo. Thus, Hannah sees himself as part of the corruption, despite his attempts to live differently. This adds a note of humility to Hannah’s own words from the opening song, “Victory Lap”: You say #notallcops. / You say #notallmen. / Yeah you insist #itsonly99%. Here, Hannah criticizes those who lay the blame for police brutality on only the “bad apples,” refusing to see systemic injustices. Yet, by the album’s third song, Hannah moves to examine himself; he is “the cop just out of frame,” unable to escape judgement with epithets of “not all cops.” All efforts of self-justification fail.

This personal corruption haunts Hannah’s moral vision. Like the psalmist, Hannah understands that “there is none who does good, not even one” (Psalm 14:3), and if so, who is wise enough to render judgment? He explores this tension even more personally on the bonus track “Laughing Stock.” Upon seeing Clayton Matchee, the torturer of Shidane Arone, now living with severe brain damage as a result of a failed suicide attempt, Hannah’s sense of vengeance withered. Was this man’s brain-damaged state true justice? It’s hard to say. The experience leaves Hannah chastened: The fool seeks retribution, the fool leaves seeking penitence. Forgive me, I know not what I do. If we all get what we deserve, and we are all implicated, what hope is there?

In the end, Victory Lap offers little hope of salvation. The album starts by yawning at the day of salvation, The day the rapture came, / a forgettable event. / The clouds, they opened up and not a single person went. (“Victory Lap”) Is this because God does not actually exist, or because there are no righteous people to be taken up? Perhaps both. It ends by contemplating the horrors of reincarnation:

I think my only fear of death is that it may not be the end.

That we may be eternal beings and must do all of this again.

Oh please lord let no such thing be true. (“Adventures in Zoochosis.”)

Corruption reigns and death comes to everyone, and to spite it all, the lingering sense of beauty comes partnered with loss. This final song begins with some of the most melodic and lovely guitar riffs on the album, coupled with the sound of children laughing. Overlaying these joyful sounds are the misogynistic words of now-President Donald Trump, describing exactly what you can do to women “when you’re a star.” This is the emotional dissonance of modern life: where there is beauty, there is also nauseating rot. The title of this final song heightens to the despair—Zoochosis—the tendency of animals in captivity to act with certain features of insanity, pacing back and forth, gnawing at their bars. When trapped in a futile world that constantly mocks you with beauty, with your failures the soul longs for freedom, but can we do anything more than slobber on the bonds of our captivity?

And what of our kids? The next generation adds depth to the lament. A parent of two boys, Hannah finally finds his pure motive for self-sacrifice. His last stand will be to shield his children.

“Dad are we gonna die?” Yes son, both you and I

…but maybe not today.

Boys, I’ve bowed to the keepers whip for so damn long

I think the sad truth is this enclosure is where your old man belongs.

But you, your hearts are pure,

so when operant conditioners come to break you in

I’ll sink my squandered teeth.

You grab your little brother’s hand run like the wind.

And if I’m not there, don’t look back.

Just go. (“Adventures in Zoochosis”)

It’s both a heartbreaking and inspiring image, an old man spending the last of his energy fighting to give his boys a few fleeting moments to break out of captivity. It’s still not much, as far as salvation goes, but with the tide rising, you take what you can get.

Propagandhi’s secular lament

Aside from the simple joys of the loud guitars and fast drums, what can a Christian benefit from this bleak vision of late modernity in the West, a rich and oppressive society hurtling toward the downfall caused by its own abuses, without hope of salvation? Along the lines of Karl Barth’s “secular parables”—stories from outside of Christianity that correspond to the Bible but need completion by the Bible—these songs are “secular laments,” true to the realities of fallen humanity, while crying out for a true response from God. In a Christian community with an anemic practice of lament and plastered-on praise, Victory Lap reminds us of heartbreak, exhaustion, and anger in the face of death, injustice, and failure. The writer of Ecclesiastes would surely agree.

The album also sheds light on the broader scope of our salvation. A side effect of evangelicalism’s conversionist emphasis is an at-times myopic focus on the individual’s eternal destiny, which then makes most other issues in life irrelevant. Worse still, when these other issues become irrelevant, the Christian imagination becomes formed by pragmatic forces like politics and money, not Scripture. When listening to Victory Lap, I am reminded that Christian salvation is meant to address issues like these, not offer an escape from them.

Consider Propagandhi’s critique of animal abuse in “Lower Order (A Good Laugh).”

His story begins on the earlier-mentioned hunting trip, meant to initiate him into manhood. He then recounts another bloody image

Don’t recall just how I got there.

To the hatchery I mean.

Stumbled through the bush on a field trip

and there it stood in front of me.

I stooped down upon the concrete pad

to verify what I was seeing.

The aftermath of stomping boots

upon hundreds of tiny, helpless beings.

Hannah sees the inherent dignity of these animals and rightly laments their mistreatment, but this is more than simple animal abuse. For him, animal cruelty is linked to toxic masculinity. There is a relationship between the men laughing at the death of a beautiful bird, the cruelty at the hatchery, and Trump’s reprehensible words about women. Going deeper, the same power-hungry swagger that insists on its own way, that is bad for animals and for women, is ultimately bad for society. This sentiment should receive resounding agreement from Christians, yet too often is dismissed as nothing more than liberal politics. Is it not true that sometimes “protecting our women” is a ploy to retain our power? In linking animal abuse to toxic masculinity, Propagandhi is on to something that many Christians in America struggle to see clearly. Their vantage point is strikingly biblical: God does not appreciate men who think they can do whatever they want.

It is this way throughout Victory Lap. The album is filled with topics that God cares about, and the Christian can and should confidently declare that God is concerned about rape, about indigenous peoples’ rights, about police brutality, about death, about corrupt leadership, and yes, even about chickens, pigs, and cows. Propagandhi’s ethics are like a slap to the face, helping the Christian wake up from cultural captivity to political platforms and see the broader scope of God’s passion for his world. Christians may sometimes forget that these issues matter to God, but God does not.

At the same time, discerning listeners cannot simply baptize punk ethics as if they are fully Christian. Hannah’s higher commitment to animals is wedded to a diminished view of humanity—that humans are also merely animals. While Propagandhi rallies against fascism, historically, the radical left can be just as oppressive. And though death is inevitable, the lack of hopeful eschatology can create a despair that ends in hatred. Though the band personally retains empathy for humankind, in more sinister hands even Propagandhi’s ideas backfire to cause untold suffering. In the end, only a robust Christian worldview can hold together the wonder of human dignity, the tragedy of human suffering, and the responsibility of human action in the world.

What might happen if evangelical Christians embraced this broader emphasis in our religion, without losing our core doctrines of Scripture and salvation? Far from losing the gospel, we will actually become more fully biblical. While Propagandhi rightly identifies the decay, the Christian story possesses something that Victory Lap does not: hope. This enables us to engage Propagandhi’s worldview, accepting the slap to the face as a needed rebuke, while offering a message of hope in response: the promise of salvation. Not merely “die and go to heaven” salvation, but the good news of God’s presence in the midst of our misery, and God’s ultimate victory over our death and decay in Christ.

When I listen to Victory Lap, my prayer is that their “secular lament” might become, in God’s hands, a bridge to the gospel. They feel injustice, which God promises to correct. They long for salvation, which Christ purchased. They see beauty, which overturns the status quo and is ultimately laden with the grandeur of God. These longings open a skylight in Propagandhi’s “immanent frame,” to channel Charles Taylor, revealing God’s presence in the darkness. In this way, punk can function as a praeparatio evangelica—a preparation for the gospel, where God has imbedded his own passion for justice in order to eventually prepare the way for salvation, where death and decay do not have the first or the final word.

Copyright © Billy Boyce

Billy Boyce is a pastor living in Arlington, Virginia with his wife, Melynda, and their four children. He recently completed his Doctor of Ministry from Trinity School for Ministry, studying the intersection of race, theology, and experience among Black pastors in the PCA.