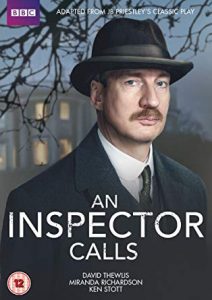

An Inspector Calls (Aisling Walsh, 2015)

I am responsible for what I know

The story of An Inspector Calls occurs in April 1912, and the action takes place in a single evening. The Birlings have gathered to celebrate the engagement of the family’s daughter, Sheila to a promising young suitor named Gerald Croft. He happens to be the son of another successful businessman, one of Birling & Company’s main commercial competitors. Mr. Arthur Birling, a confident, rather pompous man hopeful of soon obtaining a knighthood, and his snobbish wife, Sybil, are pleased with their success, even though younger son Eric is moody, not entirely dependable and struggles with a drinking problem. The Birlings have achieved the upper middle class dream. They are enjoying their personal peace and affluence in a beautiful, richly decorated house in a fictional British industrial city filled with dreary factories in which workers toil long hours in meaningless jobs for wages set as low as the market will allow, far below a living wage. From the Birling’s perspective, prospects look good all around.

To their surprise the maid informs them they have a visitor, a police inspector who is insistent on speaking with them. Not to worry, Mr. Birling assures them, this is something he can easily handle—he knows the authorities personally and is on excellent terms with them. The inspector will soon be sent away so their celebration can continue. The inspector, however, informs them that a young woman has committed suicide and that he intends to question them about her. This is met with first, surprise and then with outrage. They do not know her, they insist, she is not numbered among their friends, but even if they did know her surely her decision to end her life cannot be considered their responsibility. The idea is preposterous. People make their own choices and must bear the consequences of those choices. It’s the way life is, and the only way a well ordered society can function. But still the inspector is not put off, and insists that they submit to his interview. Slowly, as the evening progresses under the unrelenting, disquieting gaze and increasingly probing questioning of the inspector, all four family members are revealed to have directly contributed to the dead young woman’s poverty, despair and hopelessness.

The evening turns dark as consciences are aroused and then vigorously suppressed, as uncomfortable issues are raised, as past decisions are rationalized as honorable regardless of consequences, and as people face guilt in a setting in which they believe they cannot possibly be held responsible for wrong doing. And throughout the film the identity of the inspector remains mysterious, and at times, mystical. Who is this Inspector Goole and what is the source of his strangely compelling power to extract the truth and reveal the shallowness of rationalizations for decisions that are legal, economically prudent and socially respectable?

An Inspector Calls was originally written as a stage play by British playwright and socialist J. B. Priestly. The fact that it is written for the stage is clear in the film, and makes for an intimacy with the action on the screen so we are drawn into the story as it unfolds.

The play was originally understood as revealing both the shallowness of the British upper middle class, and the dark underbelly of a capitalist ideology that stays within the letter of the law while treating workers as less than persons deserving of dignity and a living wage. If you hear the film dismissed as “socialist” or “anti-free market,” do not believe it for it is not. An Inspector Calls instead makes a case for justice in a market economy in a fallen world. Priestly might have meant it as an argument for socialism—I do not know enough about him to know—but the story and dialogue raises issues entirely relevant to our modern free market society.

From a biblical perspective both the individual and the community are of significance, so that neither can be slighted. Christianity is Trinitarian, meaning we believe in one God in three persons, something that refers not to an obscure dogma but to the definition of what is really real. The nature of reality embraces both the individual (one God) and the community (three persons), and so the believer cannot commit themselves to either an ideology of the Right or the Left, to either individualism (whether Conservatism or Libertarianism) or communitarianism (whether Progressivism or Socialism). It is not that we are moderates, uncomfortably spanning both extremes but that we would argue for a third way. We will agree with both at times and disagree at other times, but always we will insist neither holds a monopoly on the truth. At each point, in every aspect of life and reality (including economics) we will seek to balance a concern for both the individual and the community.

Primarily, however, I see An Inspector Calls as about human responsibility. Economics is merely one part of that, as it is in daily life. Those of us who are eager to speak of our love for the truth must remember that there is a responsibility that comes with knowledge. If I know my neighbor is suffering that knowledge is not neutral but demands a response. In a fallen world it is sometimes best not to know.

I know of no one who has written more clearly on the Christian responsibility of knowledge than Os Guinness. And so I will let him speak rather than try to reword what he has said so well:

Modern knowledge is characteristically noncommittal. Much is known, but all is consequence-free. What we know and what we do about it are two different things. Various roots of this noncommittal style of knowing could be explored. Philosophically, for example, the Anglo-Saxon world in the twentieth century has been dominated by what John Dewey described well as “the spectator theory of knowledge.” Owing to the triumph of such forces as empiricism and science, the myth is prevalent that knowledge is objective, universal, and certain—and therefore neutral, detached, impersonal, uninvolved and irresponsible. What we do with what we know has nothing to do with knowing itself.

Other factors have reinforced the noncommittal character of modern knowledge. An obvious one is the impossible overload of modern information. Another is the essentially detached style of the media—epitomized by Christopher Isherwood’s famous but absurd line in A Berlin Diary, “I am a camera with its shutter open, quite passive, recording, not thinking…”

The Christian idea of the responsibility of knowledge is rooted in the notion that God is there and that he speaks. He is therefore the one with both the first decisive word on life—in creation—and the last decisive word—in judgment. Thus human life is essentially responsible, answerable, and accountable. Such responsibility of knowledge is the silent assumption in many basic doctrines. Sin, for example, is a deliberate violation of the responsibility of knowledge—human beings become responsible where they should not be (playing God) and refuse to be responsible where they should be (denying guilt).

This responsibility of knowledge is also embedded in the root meaning of many of the biblical words. For example, the Hebrew word “to know” includes the meaning “to care for.” The idea is that “knowledge of” something is “power over” it, “responsibility to” it, and “care for” it. Thus when the Proverbs say that “A righteous man cares for his beast, but a wicked man is cruel at heart,” the Hebrew word “cares” is actually “knows.” It signifies that a righteous person has a caring knowledge that responsibly treats his animal with integrity—that is, true to the truth of what it is before God. The wicked person, by contrast, understands all knowledge in relation only to himself or herself rather than to God and therefore “understands no such concern.”

We can see the biblical understanding of the responsibility of knowledge supremely in Jesus. For where the first man, Adam, severed the link between knowledge and responsibility, the second Adam reunited them. Refusing the devil’s temptations to make claims that had no consequences, Jesus set his face toward Jerusalem and the cross. The responsibility of his knowing who he was and what he had come to do marked his way to his death…

Possible applications are myriad—in our attitudes to education, careers, specialization, elitism, cynicism, resistance to evil, and a score of different areas. But the recurring motif is the costly obedience of Christian knowing. Knowledge for the Christian is never noncommittal nor consequence-free. Knowledge carries responsibility. Knowing means doing. What we do with what we know is what Christian knowing is all about.

An Inspector Calls was not made primarily to be entertaining—though I find it so—but to prompt thoughtfulness. As a result it will probably not win awards or draw large audiences. It doesn’t invite reflection as much as demand it. With an ensemble of veteran actors, the film asks us to take another closer look at life and in doing so helps us to be better stewards of our humanness.

Don’t watch it unless you are serious about life and faithfulness. But please do watch and discuss it.

Questions

1. What was your initial or immediate reaction(s) to the film? Why do you think you reacted that way?2. In what ways were the techniques of film-making (casting, direction, lighting, script, music, sets, sound, action, cinematography, editing, etc.) used to get the film’s message(s) across, or to make the message plausible or compelling? In what ways were they ineffective or misused?

3. What ideas or values are made attractive in the story? How is this done?

4. Some want to dismiss An Inspector Calls by saying it is merely a story designed to make viewers dislike the free market and be open to socialism. How would you respond? Does the free market in a broken world—and the players in it—ever serve injustice rather than promote the common good?

5. Are there ideas or values promoted by the story with which you would disagree? What are they, how were they presented in the film, and why do you disagree?

6. With whom did you identify in the film? Why? With whom were we meant to identify? How do you know? Discuss the main characters in the film and their significance to the story.

7. Who is Inspector Goole? Why is the character made mysterious, even mystical in the film? What does this element in the story bring to the impact of the narrative?

8. Do you agree that a primary theme in An Inspector Calls is the responsibility of knowledge? Why or why not?

9. At one point in An Inspector Calls Inspector Goole says this about the young woman who took her own life: “But just remember this: There are millions and millions of Eva Smiths and John Smiths still left with us with their lives, and hopes, and fears. Their suffering, and chance of happiness all intertwined with what we think, and say, and do. We don't live alone upon this earth. We are responsible for each other. And if mankind will not learn that lesson, then the time will come, soon, when he will be taught it in fire, and blood, and anguish.” Do you agree? Why or why not?

10. To what extent does the world of advanced modernity agree with the notion of the responsibility of knowledge? Where do you see this? To what extent has this infiltrated the church? How do you know? To what extent has it infiltrated your own heart and mind? What plans should you make?

Source

Fit Bodies Fat Minds: Why Evangelicals Don’t Think and What To Do About It by Os Guinness (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Books; 1994) pages 146-148Goole quote online (https://www.imdb.com/title/tt4271918/quotes/?tab=qt&ref_=tt_trv_qu)

Movie Credits: An Inspector Calls

Starring:

Sophie Rundel (Eva)

Miranda Richardson (Sybil Birling)

Ken Stott (Arthur Birling)

Finn Cole (Eric Birling)

Chloe Pirrie (Sheila Birling)

Kyle Soller (Gerald Croft)

David Thewlis (Inspector Goole)

Gary Davis (Alderman Meggarty)

Director: Aisling Walsh

Writers: J. B. Priestley (original play), Helen Edmundson (adaptation)

Producers: Roanna Benn, Greg Brenman, Lucy Richer, Howard Ella

Music: Dominik Scherrer

Cinematography: Martin Fuhrer

UK, 2015, 87 minutes

Rated PG