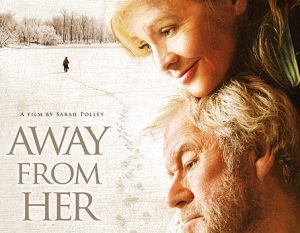

Away From Her (Sarah Polley, 2006)

Losing Memory, Losing Oneself

Promise me you’ll never forget me because if I thought you would I’d never leave.

[Winnie the Pooh]

Fiona Anderson (played with simple, heart-breaking honesty by Julie Christie) has been showing signs of forgetfulness, a slow decline in functioning. While washing dishes after dinner with her husband she places a newly cleaned pan in the freezer instead of in its accustomed spot under the sink. Post-it notes, neatly penned labels detailing contents on drawers and cabinets have proven insufficient in holding back the loss of memory. Though she and Grant (played by Gordon Pinsent) have lived in the same house for years she wanders off the cross-country ski tracks they use and gets lost in the cold. In a frightening scene Fiona wanders among birch at the edge of the frozen lake, drops her skies and poles on the ground and lies down in the snow, arms outstretched. The camera (always our point of view) watches from above, helpless to intervene and frightened at the possibilities. It is one thing to be alone and lost; to be within sight of home and safety and not have memory to recognize it is to be lost without hope of finding our way. At dinner with friends she goes to pour wine, but forgets the word, a senior moment stretching into a senior tragedy when it becomes clear that even hearing the word spoken by Grant does not erase her bewilderment. An interview with a medical professional is both wrenchingly revealing and inadvertently demeaning, when simple obvious questions provoke not answers but confusion and embarrassment. Once again, with Grant, we watch helplessly.

As her dementia grows, Fiona is painfully aware of her intractable problem. “I think all we can aspire to in this situation,” she says at one point, “is a little bit of grace.” Unlike many such patients, Fiona decides to enter an assisted living facility, and leads a mourning Grant through the intake process. During the initial month in the facility, Fiona develops a close bond with Aubrey (played by Michael Murphy) a man she insists worked for her grandfather in a hardware store as a teenager, though this memory isn’t true. Grant visits faithfully, but Fiona’s affection and attention has shifted away from him to another. It seems a painful punishment for the affairs Grant enjoyed decades earlier as a young university professor with young willing female students.

Over the course of Away From Her (2006) we watch a slow progression—as Grant notes, an unfortunate word choice—as Fiona slips into greater and greater forgetfulness, confusion, disorientation, dependency, and finally a deterioration that encompasses more and more of her being, body and mind, unto death. Or, in institutional terms, eventually she has to be moved to the dreaded second floor of the memory care facility, to live among those whose bodies linger on, such as they are, but whose minds have a medical label: Dementia of the Alzheimer’s Type, as the DSM-IV puts it.

We all know forgetfulness. The other day I could not remember a word, and went to Margie’s office to ask her to help me remember it. I’d tell you the word, but I don’t remember, and I’m not saying this just for effect. It’s gone, and no, I am not going to ask her to help me remember it a second time. Nor am I am being morbid about being in my sixties, since I know we all have such moments. Still, I have more trouble remembering some things that I used to be fairly sharp about—like movie titles and actor’s names, or where some text appears in the Scriptures. I’ve started a cheat-sheet for Bible references I want to keep track of, and have begun to think that having constant access to imdb.com might be a good reason to upgrade my cell phone to include Internet access.

There is an intimate link between memory, remembering and a sense of significance, so that forgetfulness does not merely erase distinct memories but seems to eat away the foundations of our being. “I think I’m beginning to disappear,” Fiona says at one point. Life makes sense only within a narrative that provides structure and meaning to reality, and the loss of memory reduces life to bare existence, a succession of unrelated details. When regrets or loss interrupt our happiness we may yearn to forget them, but as Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind (2004) revealed, such forgetfulness is not always the grace we imagine.

It is not surprising that the Scriptures are rich in the themes of memory, remembering, and the danger of forgetting. Memory is explored not just in relation to human beings, but also to the nature of God. The covenant making God who reveals himself in history is the One who remembers (Genesis 9:15-16). The people of God were to remember their painful past in slavery and God’s gracious rescue, so that they would be eager to act with justice and compassion to the powerless, the alien that live within their community (Deuteronomy 16:12). When the Old Testament people of God forgot God’s grace, the Hebrew poet called it rebellion (Psalm 106:7). The Teacher in the wisdom literature meditates on life and meaning, concluding that at the core of things is the need to remember one’s Creator while still young (Ecclesiastes 12:1). In a wonderful irony expressing his mercy the God who always remembers his covenant graciously promises to always forget his people’s misdeeds (Isaiah 43:25). A thief crucified beside Jesus expresses hope by asking to be remembered, and is promised paradise (Luke 23:42-43). The Eucharist is not just a ritual of future hope but of remembering the past (1 Corinthians 11:25-26). The list could be easily expanded. If nothing else, this biblical emphasis throws into stark relief how dementia captures so much of the horror and brokenness of the fall.

Grant’s faithfulness in visiting regularly, and their financial ability to place her in a better-than-average facility for care are both positive things in an otherwise grievous situation. Though his earlier promiscuity may not have made his decision easier, Grant’s willingness to allow Fiona her attachment to Aubrey probably eased Fiona’s transition to assisted care. “Sometimes you have to let go,” the movie tag line says, “of what you can’t live without.” Now that they must be apart, Grant’s heart speaks a deeper truth he expresses with quiet longing, “I never wanted to be away from her.”

It is difficult to think of a more painful effect of the brokenness of our sad world. Sliding into dementia, no cure known, often occurring as a person ages, a disease of the brain that can occasionally afflict people in their 50s, a lingering living on while it seems that humanness itself is slipping away. I fear almost nothing more than this, a dread of returning to a burdensome infancy for those I love and for whom I desire freedom not burden. I’m far less fearful of death than I am of this.

The Western church will need to speak of euthanasia with greater compassion and thoughtfulness as the population continues to age. Fiona showed courage entering the assisted care facility. “I’d like to make love, and then I’d like you to go,” she says to Grant. “Because I need to stay here and if you make it hard for me, I may cry so hard I’ll never stop.” It seemed impossible to watch that scene and not think of my best friend, my wife, and wondering what I would do. I know I have no desire to enter such a place myself, instituting the need for my family to visit me when I may not even remember who they are. Too much of the discussion about euthanasia in the church has involved easy sound bites and has addressed easy situations—much more substance and compassion will be needed as relatively more people grow old enough to begin the painful slide into dementia.

The church also should take more of a lead in helping families discuss the problems of aging and dementia. Perhaps this would be a better topic for an adult class than some of the usual oft-repeated fare. Perhaps there is research that shows whether many families thoughtfully discuss and plan for the possibility of dementia in an aging family member, but my limited anecdotal evidence suggests such honest interaction is rare. Though it is a topic no one wants to face, is politely ignoring it until dementia is evident a wise choice? Perhaps this is one way to update the care the 1st century church showed to the widows of its day, when they displayed sensitivity and practical ministry to the unfortunate brokenness of life afflicting those who could no longer care for themselves.

Biblical faith requires assuming some certainties. We remain God’s covenant people regardless of the illness that afflicts us. Though the result of the fall, illness, including dementia is no cause for shame. It is God’s grace not our memory that assures us of his love, presence, and acceptance. Even unlikable, difficult patients are worthy of care because they retain God’s image. Family caregivers are worthy of care for the same reason. Loving, safe, and trusted community should assist caregivers in the difficult task of determining when the patient has outgrown their ability to care for them and needs professional attention. And caregivers need to be helped to see that receiving care themselves is not a sign of weakness or cause for shame.

This past weekend Margie and I visited a beloved maternal aunt of mine suffering from Alzheimer’s. Each visit the disease is more evident, her memory more ravaged, her functioning declining, her emotional swings less rational and more abrupt. When I was a child being with her was a safe place for me, when I felt acceptance rather than the solemn watchfulness on the lookout for my next, inevitable failure that was my constant companion at home. Some of the changes in her are almost amusing, in a perverse way. She’s had fisticuffs with some of her fellow patients, men in the facility who were, she said, harassing someone and she wasn’t going to put up with it. She’s even taken to occasionally swearing, my dear Fundamentalist aunt standing next to her bedside table where her old worn King James Bible lies open to her reading for the day. I know it is not her, not really, but the disease. As it is when she rails angrily at me for taking her cane with us when we take her out to lunch. While we eat she asks the same question six times, and we answer each time as if we hadn’t heard it before. Besides the vital addition of prayer, there seems to be little practical difference to our response as Christians to my aunt’s dementia and the care outlined for Fiona in Away From Her. Nor need there be any difference, given the grandeur and extent of God’s common grace expressed so freely in his creation. She claims she stays in her room alone, but the staff tells us otherwise, and when we arrive for lunch she seems happy sitting with the other residents in the main lounge. In the car she tells us she avoids the lounge. I have always been able to make her laugh, and I am happy this grace remains. Over lunch I tell her stories from our past, and it makes her happy to remember through my memories. The fact that I am repeating some of the same stories from the last visit is a secret that breaks my heart.

The church needs to be alert to growing despair as people watch loved one’s lose their memory. To gently remind them that though forgetting is sad beyond words, the final grace is not our remembering God but his remembering us. St. Paul himself contrasts the two modes of knowing (Galatians 4:9). God’s people, the apostle assures us, are “known by God” (1 Corinthians 8:3). And that is the certain memory—the only fully certain memory—in which we can finally, fully hope.