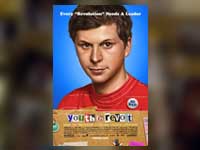

Youth In Revolt (Miguel Arteta, 2010)

Based on the irreverent coming-of-age novel by C. D. Payne and directed by Miguel Arteta, Youth in Revolt doesn’t begin there—with the revolt. Instead it starts benignly, in the bedroom retreat of a teen who knows he’s a misfit. Literate, introverted, besotted by Italian cinema, Nick Twisp (played by Michael Cera) seems an unlikely candidate for a rebel. But at 16, he’ll do anything to get a girl.

On a vacation with his mother (Jean Smart) and her live-in boyfriend (Zach Galifianakis)—they head to the boyfriend’s friend’s cabin for a week away, only to discover it’s a rusting trailer in a park called the Restless Axles—Nick meets a girl his age, Sheeni (played by newcomer Portia Doubleday), also there on vacation with her family, and falls hard. At first, Sheeni is flirtatious, indulging Nick’s infatuation. But then she drops the bombshell: There’s a boyfriend back home, and Nick can’t match him for daring and bravura.

In a bid to win the Francophile Sheeni over, Nick develops an alternate persona, François (also played by Cera)—his opposite in every way: contemptuous of authority, recklessly risk-taking, sexually experienced. Wherever Nick would play it safe, François urges rebellion. The turning point comes when Nick follows François’s lead and stages a car wreck—only to have it blow up in his face (almost literally). Will Sheeni like him better if he’s not the shy, unassuming kid he’s been up till now? That’s the bid, and the rest of the movie is the telling of the resultant tale.

I found myself surprised by the affecting power of some of the scenes in this offbeat, down-to-earth comedy. You don’t normally go to a hormone-drenched teen flick to encounter profundity, but there are glimpses of it that flicker through. Then, too, there’s the lovely cinematography. A number of close up shots in the film highlight even the slightest and most emotionally revealing facial movements, the barely noticeable twitch of a lip or glimmer of an eye that speak volumes. I thought of Jean Bethke Elshtain’s recent description in Books & Culture of some of the camera work in Public Enemies: “The close ups help us once again to appreciate why movie stars—real movie stars—are different from the rest of us, physically blessed with a kind of preternatural grace and beauty. The camera magnifies rather than diminishes these qualities. They are larger than life.”

As one might expect, the chief theme here is desire—the desire for sex and, beyond that, for love. Without spoiling the ending completely, I’ll say that Nick Twisp’s redemption, his moment of self-understanding and his first real sense of rest and peace from the vortex of adolescence, involves the loss of his virginity.

There’s no denying the power of this age-old trope: Being loved by another human being, even in a brief and fleeting moment, can have redemptive, healing power. But is it redemption of the deepest sort? Can sex really liberate and restore us in the way we most need and want liberation and restoration?

Christianity proclaims a different kind of salvation, one revealed not in moments of adolescent passion but in a cross and empty tomb and in broken bread and shared wine. “Early Christians were seen as atheists because they rejected the proposition that Caesar saves,” says Rodney Clapp. “Christians [today] would be little less revolutionary in their ‘atheism’ if they now rejected the proposition that sex saves.”

Proclaiming the salvation Christ has accomplished to teenagers like Nick Twisp (not to mention lonely and desiring people a few years beyond their teens) must take their desires seriously but also take them as pointers to even deeper needs and desperate conditions. The love Christ embodies is more profound, more powerful, more redemptive even than a first love—and as this movie shows, that’s saying a lot.

Copyright © 2010 Wesley Hill