Why Bother With Culture?

You’ve heard the criticism. Perhaps you’ve been a critic yourself. The disapproval often goes something like this: “Why do you bother messing around with novels, film, popular music, poetry, sculpture, dance… when what people need most is Jesus? With the limited amount of time we have in life, why not devote our energies to teaching people the Bible?” A deceptive logic underlies the criticism because, of course, there is nothing in the universe greater, grander, and more needed than Jesus, and there is nothing more essential to life than knowing him as he is revealed in the Scriptures. If that premise about Jesus and the Bible is true (and it is true), then why do we… no, why should we bother messing around with the stuff of culture, the so-called lesser things that so often take people on a path of idolatry away from Jesus?

This year, I’m preaching through the book of Acts, and in my study I came across an answer to that question from a source that surprised me: the magisterial Welsh preacher and churchman from the mid-20th century, D. Martyn Lloyd-Jones (1899-1981). In 1927 Lloyd-Jones entered pastoral ministry, leaving behind a promising career in medicine. However, his years of medical training, in addition to sharpening his skills of inquiry, observation, and analysis, softened his heart as he confronted the sorrow and suffering of those who had come to him for help. Known affectionately throughout his life as “The Doctor,” Lloyd-Jones’ prowess as an expositional preacher was matched by a deep passion for holiness. Os Guinness, who was under Lloyd-Jones’ preaching and pastoral ministry for a time, once said that like no one else he knew, Lloyd-Jones preached as if he had just come from the presence of God. So, why bother messing around with lesser things? Here is Lloyd-Jones’ answer from his sermon on Acts 3:12-18, Peter’s sermonic explanation of the healing of the lame man at the Temple (not exactly the text I would have thought of to call the Church to cultural engagement):

To me this is in many ways the most astonishing thing of all. Peter’s sermon did not even start with the Lord Jesus Christ. Have you ever been struck by that? Peter had healed the man “in the name of Jesus Christ of Nazareth;” yet when the people said, “What is this?” Peter’s answer was: “The God of Abraham, and of Isaac, and of Jacob.” I speak carefully because I know I am liable to be misunderstood at this point, but this to me is a very vital part of Christian teaching and of the Christian message. You do not start with the Lord Jesus Christ. I wonder if perhaps most of our troubles in the Christian church today are due to just that. We must start with God. We start with the whole message of the Bible.

When Lloyd-Jones says that we must start with God, note that he equates this starting point with the over-arching message of God’s Word. To start with God means to know him first as he has made himself known. To start with God means to view the Creation and especially God’s image-bearers through the eyes of the Creator. All hope of truth, beauty, goodness, and justice must be brought before the Lord God Almighty, Maker of heaven and earth, with the question, “How can these things be?” Lloyd-Jones continues:

There is a modern conception of evangelism that regards it as simply saying to people, “Come to Jesus.” This view says you do not need to talk about repentance; rather, if they are in trouble or are unhappy, you just tell them to come to Him. You start with Him and end with Him. But that is not Christian preaching…

The first step in Christian preaching is to tell men and women that they and all their problems must always be considered in connection with God. That is the whole message of the Bible. You do not start with particular problems, but with men and women as they are in this world. How are they to be understood? It is in their relationship to God….

Men and women in their folly have rebelled against Him and brought chaos down upon themselves, but Christianity brings the message that God is concerned and is determined to do something about it. So we do not start with Jesus Christ but with God, who thought out a plan of redemption before the foundation of the world. It is the most comforting and consoling fact that though statesmen fail, having done their best, though clever men propound their theories but do not help us, and through civilization advances but immorality increases, in spite of that, all is not lost and all is not hopeless because the everlasting God is concerned.

“Men and women as they are in this world.” There it is, the first step in Christian living, and Lloyd-Jones’ answer to why we bother with the stuff of culture. With his surgical incisiveness, he exposes the hastiness of our hearts to treat people as objects, things to be fixed. No so with Jesus. His critics said derisively, “Look at him. He’s eating and drinking, a glutton, a drunkard, and a friend of sinners” (Luke 7:33). Of course they were wrong about his behaving sinfully, but all the rest is completely true.

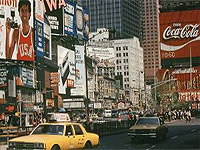

“Men and women as they are in this world.” The clamorous conversations and creative quests that produce the mosaic of culture reveal the deep human struggle to make sense of life as it really is—the longing to be accepted and loved, to be forgiven and vindicated, to discover and hope, to feel and understand, to be known and to matter. With that shared, irrepressible human heart-longing, we gesture with a half eaten bagel over a cup of mocha latte, we sit in a darkened theatre drawn into the story playing out before us, we huddle in recessed pools of gallery light remembering to keep our voices down, we pace with moody irritation scribbling figures under fluorescent laboratory lights. As followers of Jesus, we step into a world that does not know him, but that yearns deeply, so that we may say with honest understanding and conviction, “My heart longs for the same things, too.” We mingle our lives with “men and women as they are in this world” sometimes glorious in creativity, sometimes derelict with despair, and we listen for the “hope of all the earth,” the “dear desire of every nation,” the “joy of every longing heart” (Charles Wesley). This is the way the world is, and this is where we begin to love the world into which our Great God has stooped low to whisper in his most comforting and eloquent Word, “I have heard your cry, and I have come.” Jesus has come, eating and drinking, a friend of sinners.

Lloyd-Jones rebukes me for those times when I been driven by my spiritual agenda to start with Jesus as “the answer”—too often I have not listened and I have failed to love. Yet, I believe Lloyd-Jones is affirming that the truly God-focused Christian life never detaches from the human encounter with life—our life in Christ is inextricably fused with the stuff of culture. His words bring me great encouragement to continue reading, listening, playing, creating, because (frankly) I am often wearied by the criticism of those who belittle our bothering to attend to “men and women as they are in the world.”