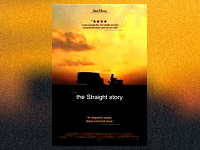

The Straight Story (David Lynch, 1999)

No movie in recent memory so exemplifies the wisdom of the less-is-more principle than The Straight Story, David Lynch’s G-rated, true story of Alvin Straight, the man who rode his lawnmower across Iowa to visit his brother in order to be reconciled to him before his death. Though this film is not as short as many (one hour, fifty-one minutes), dialogue is kept to a minimum, and the most exciting action is that of Alvin’s John Deere careening down a hill out of control. Alvin, played by Richard Farnsworth in an Oscar-nominated performance, does encounter a number of people and have a lot of experiences during his six-week journey, but Titanic this is not. What it is, is a powerful statement of the gospel of humility and forgiveness.

Lynch tells much of the story with his camera. Recurrent themes of the stars of a late summer Iowa evening, the sweeping vistas of corn and wheat fields, close-ups of members of the present older generation, showing their sadness and strength build a statement that focuses on the simple, primary virtues of life as it is supposed to be lived: the beauty of nature, the worth of work that grows things out-of-doors, the knowledge that comes through suffering.

Nowhere is Lynch’s use of the camera to speak more evident than when Alvin finally crosses the Mississippi. After three hundred miles and almost six weeks, he is just about there. Alvin goes over the bridge entirely alone, rejoicing in the steady, slow clack of the lawnmower as it rides along, looking left, right and down through the cracks of the bridge to see the water as it tells him of the near-accomplishment of the journey. It is a moment of triumph without a single word, just the tears of joy on an old man’s face that signal to him that he has not suffered in vain. Powerful and deeply moving without being maudlin, the scene causes us to feel the special sense of rightness in what Alvin is doing; his journey will be worth the effort after all.

Lynch uses the camera in other ways. Off-camera noises build tension in the viewer as we are made to be as patient as Alvin in order to find out what we want to know. In the opening scene of the movie, for instance, a helicopter shot of the empty main street of Laurens, Iowa becomes a crane shot of two modest houses with an overweight woman sunning herself optimistically while wolfing down cream puffs and drinking iced tea. She gets up to go fill her plate again and while gone, the camera slowly moves in and rests on a single window of the house next door. We hear an ominous thump from within, one that would have alarmed the woman had she heard it. We do not find out what has happened until at least five minutes later when we learn that Alvin has fallen and cannot get up without assistance. It seems like an eternity to us, but we learn something of the patience that Alvin has, as he calmly lays there on the floor waiting for someone to find him so he can get up. The same device is used later in one of the funniest scenes in the movie (and there are many) when a frustrated woman runs over a deer, but I will leave that one to your viewing. I cannot remember when I have laughed so hard.

But the real strength of this film lies in the character of Straight himself. Farnsworth’s performance (as well as those of all the characters in the film, especially that of Sissy Spacek who plays his full-grown, retarded daughter) is an unbelievably wonderful blend of cantankerousness and warmth. Full of wisdom that he has gained from the years of his experience in his family, and also especially the Second World War, Alvin gives us lines, stories and images that lift our spirits and make us want to “be like that when we get old.”

His patience, stubborn adherence to what he knows he must do, no matter how crazy it might seem, his ability to listen to others or even simply tell from looking in their eyes how he can help them are woven together around a story that is dominated by one single motivation: Alvin Straight, proud master of his own fate, knows he needs to humble himself and go see the brother to whom he has not spoken in over eleven years. It does not matter what it will take to get there, he must do it simply because it is the right thing to do. What he learns along the way, and what others learn from him, is worth infinitely more than all that Alvin Straight does not have—the money, power or fame so coveted in our possession-drunk culture. And what we learn from this movie is worth even more than that.