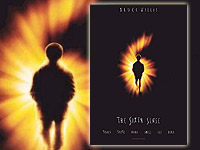

The Sixth Sense (M. Night Shyamalan, 1999)

The Sixth Sense was my choice to receive the 1999 best movie Oscar, given the five nominees the Academy selected. Better than any of the others, Sense combines good writing, good acting, good directing and all the other practical aspects of making a movie that stimulates the heart, challenges the mind and advances the soul.

Christians who have seen the movie may have questions about whether the movie is edifying. It does raise controversial issues like whether or not ghosts exist and, if they do, whether or not we can interact with them—not only speaking to them, but helping them and allowing them to help us. These sorts of questions will not be answered in this review, though they are good ones to ask in a late-night discussion after viewing this creepy masterpiece.

Starring Bruce Willis as Malcolm Crowe, a caring, though doubting, child psychologist, the movie begins with him being shot by one of his former clients—grown-up now but not “cured”—on the very night Crowe was honored by the city of Philadelphia for his accomplishments. A few months after the shooting, the psychologist encounters a small boy who suffers from the same delusions the shooter did; in his own words: “I see dead people.”

Haley Joel Osment (who plays the boy, Cole Sear) and Toni Collette (Lynn Sear, Cole’s widowed mother) were both nominated for Academy Awards and Willis should have been. The portraits they paint are so convincing that we buy everything else: thermostats which suddenly plunge, teen-age boy ghosts with half their head blown away, counseling appointments in churches, schools, on the street. Willis is a fine actor, unselfishly making those around him better and allowing them the stage when they should have it. Collette plays a stereotypical character—the over-worked, trying-to-make-ends-meet Mom who loves her son but is baffled and distraught by his behavior—with such a wide range of emotion and effortless ease that she is thoroughly believable.

But the movie belongs to Osment, the 9 year-old boy suffering from encounters he does not understand and wants even less. In what has been called the best performance by a child star ever, Osment must be both Everyboy—laughing and playing with friends—and an extraordinary outsider with a gift that isolates him from all of us. He is alternately the child playing with his toy soldiers and the tormented bearer of wisdom that sometimes exceeds that of his adult counterparts. Osment’s work will make Cole Sear one of the longest-lasting characters in the memories of movie-goers everywhere.

The performances, outstanding as they are, should not overshadow the very fine work Night M. Shyamalan did as both scriptwriter and director, presenting us with a film that is always, strangely, both creepy and yet tender. Horror is never used with the sadism of Wes Craven’s teen slasher films. Cole’s mere vulnerability, huddling in the tent he has constructed in his room, is enough to cause us concern.

Structuring the movie around relationships—Cole with his mother, Malcolm with his wife, and above all Cole with Malcolm—gives the movie a tenderness that belies the rubrics “horror film” or “thriller” and is the genius of Shyamalan’s narrative frame. The idea that “perfect love casts out fear” wells up in the climax of the film with such a power that one is left breathless at its ability to right even the most heinous wrongs.

Although the film on first viewing does not appear to be religious, the truths of divine assistance and supernatural reality are present in the film. They are in the background, shaping the character of young Cole as he tries to sort out what is happening to him. The first time he runs from Malcolm, Cole seeks asylum in a church. The importance of this common symbol for God is emphasized by a tilt shot, panning from the street up to the top of the steeple as Malcolm looks on. The discussion that Malcolm and Cole have about how churches were used in olden times by people seeking asylum from things they fear strengthens the impression that the boy is looking for God’s help. Even more important, immediately prior to that discussion, Malcolm discovers Cole repeating the Latin phrase de profundis clamo te domine, a close quotation from the Vulgate of Psalm 129.1: “Out of the depths I cry to You, O Lord.” In the shrine Cole builds for his protection in his room, statues of Jesus and icons of Mary abound. Cole and his mother even say grace at the table.

Malcolm Crowe on the other hand does not have any clear indications of faith in his character; his psychology and his wife are his life, and both are coming apart at the seams. It is only as they work together, struggling to understand the remarkable sixth sense the boy has and its purpose, that it becomes clear Cole’s prayers are answered in the person of Malcolm, and that Malcolm who did not even know what his own needs were, finds his answers in the love and wisdom of the boy. God, the unseen helper in all this, displays His common grace in a profound and moving way, touching us, as He so often does, with the grace of others.