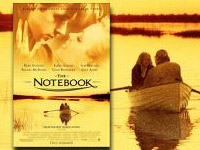

The Notebook (Nick Cassavetes, 2004)

When, in the blush of youth, people consider marriage, there are at least two mistakes they often make. One is not taking into account how hard it is to make love work. They really believe deep-down this dream-like state of euphoria will last forever in their relationship. Full and mature love requires the regular decision of the will to love the other person in spite of their shortcomings; the young person is often blind to those shortcomings altogether, much less loving someone in spite of them.

The second mistake affirms that it is not possible to love more than one person, indeed to be married “successfully” to more than one person. Much hand-wringing and trauma goes into finding “the only one for me.” Courtship sometimes forces a choice upon the lucky one (or is it lucky?!) who has to decide between two people for his or her life-long partner. The chooser, however, need not think that the feelings they have for one or the other of their beloveds cannot be love. The idea that true love only happens between two people for whom the stars have magically aligned simply does not fit reality. Love is more complex than that, as the Bible, and life, teach us.

It is rare for recent American film to show this sort of realism, especially with younger characters, but two current movies do a fine job of raising issues and providing models for us to consider, while a third shows how bad a movie it actually is by botching the whole discussion.

The Notebook, a weepy study of love and its vagaries, provides the most stimulation to think about love and its connection to marriage, commitment, desire, and destiny. Adapted from Nicholas Sparks’s novel, the screenplay splits time between the present in which we find two older residents of a nursing home, one of whom reads to the other a story of young love, and the past in which that story is acted out between the exquisite Rachel McAdams (Mean Girls) and the equally adept Ryan Gosling (The United States of Leland). The present-day story, though tender and winsome in many ways, leaves much to be desired. James Garner and Gena Rowlands labor under the sugary pretensions of overblown dialogue and silly plot devices, thrown in simply to make points for a sweet, but finally maudlin, relationship.

Gosling and McAdams, however, play the young 1930s lovers Noah and Allie with a verve, wit and wisdom that pulls one, in spite of oneself, into rooting for them and the success of their summer love. When, after a separation engineered by Allie’s mother, they chance upon one another again one college degree and one war later, Allie is engaged to a fitting suitor—money, status and education to equal her own —a likeable and caring character who vies with Noah for the audience’s heart, as well as hers. Here the writing of the movie noticeably improves, and Allie is faced with choosing between two men who love her deeply, and for both of whom she feels a real love.

What she will decide is never really in doubt in our age of happy endings, but the important thing about this film is that the decision to marry one over the other is not sealed off into neat either/or categories like heart vs. head, or money vs. happiness. The only either/or that is presented is a believable and commendable one: the aching of the heart vs. the pull of perceived security. Allie and Noah are portrayed as fighting with each other, cognizant of each other’s weaknesses and aware that their difference in class will create difficulties for their marriage. Though these important aspects of any relationship are not thoroughly explored (seemingly more in the interests of time than anything else), the film is clear that both characters understand marriage to be hard work and that is enough.

Much more could be written about the choice Allie has to make and its plausible presentation, but before leaving the discussion of this movie, I should warn the reader that the boundaries of the PG-13 rating are severely tested here. Though technically the movie lacks enough nudity to warrant an R rating, the erotic tension in the love between Noah and Allie is explicitly, and more than winsomely, displayed. Linking sexual activity to the playfulness, discipline, passion and beauty of love always charges a film with much more erotic electricity than sheer nudity does anyway, and this movie proves it in spades. It is not for the unmarried teen, and those who suffer from the oppression of lust should be wary of its potential for adverse impact upon them.

Neither Spider-Man 2 nor The Terminal approach the supercharged atmosphere of The Notebook, but for entirely different reasons. In Spider-Man, the relationship between Mary Jane Watson (Kirsten Dunst) and Peter Parker/ Spiderman (Tobey Maguire) is not the full focus of the plot. Parker’s distractions from being a superhero also include problems at work, at school, with his friend Harry Osborn, and even with his dear Aunt May. The dominant aphorism of the first film, “With great power comes great responsibility,” haunts Parker as he encounters the desires and challenges of growing into manhood and struggles with the way having super powers interferes with that process.

But Peter’s relationship to Mary Jane is crucial to his development, and the treatment of that relationship is handled with a subtlety and depth that is generally unheard of in comic book films of this type. Without spoiling the film for those who have not yet seen it, suffice it to say that Parker has interpreted his life’s responsibility as Spider-Man to mean that he can have no close relationships because if anyone were to find out his secret identity, those whom he loves would be at risk. Mary Jane points out the fault in that logic to Peter, when she reminds him of two important things: that she has a right, too, to decide whom she will love, and that love is worth risking everything for. The idea of two becoming one is even introduced in her speech at the end of the film:

I know you think we can’t be together, but can’t you respect me enough to let me make my own decision? I know there’ll be risks but I want to face them with you. It’s wrong that we should be only half alive… half of ourselves. I love you. So here I am, standing in your doorway. I have always been standing in your doorway. Isn’t it about time somebody saved your life?

Mary Jane is also faced with the equally difficult decision of being in love with John Jameson, astronaut, millionaire and all-around good guy. Again, the script does not do the standard, expected thing: we like John Jameson and can understand fully Mary Jane’s love for him. As in The Notebook, but in a much more chaste way, sexual attraction helps Mary Jane make her decision, as she tries out the famous upside down kiss on John. But it is the friendship that Mary Jane and Peter have always shared, coupled with the attraction of the dashing hero Spiderman, that helps her decide for Spidey/Parker in the end.

The third of our films, the Steven Spielberg directed The Terminal, is not only by far the worst of the three, it is also the farthest from presenting a picture of romance and marriage that would be encouraging to Christians. It is hard to believe that Spielberg, accompanied by many of those who worked with him on such masterpieces as Saving Private Ryan and Catch Me If You Can could not have seen the disaster that this film’s screenplay is: characters that are either underdeveloped, unnecessary, or completely silly; plot points that have holes so large one could fly all the terminal’s Boeing 747s through them lined up wing-tip to wing-tip; and absolutely the worst dialogue heard on film in a major production in decades. Even Janusz Kaminski’s cinematography seems to try to ape the mysticism of The Lord of the Rings (or worse, Willow) instead of quietly supporting what could have been a very successful love story. Suffice it to say, if the film did not turn in creditable performances by Tom Hanks, Catherine Zeta-Jones and Stanley Tucci in its principal roles, it would have been a complete disaster. As it is, the film is merely immediately forgettable.

But here again, a character faces the prospect of deciding between two loves: a faceless hunk about whom we know only that he is great in bed and that he treats Catherine Zeta-Jones like dirt (I told you this movie was unbelievable), and the loveable, caring immigrant played by Hanks, who is doomed to stay in JFK until he is released by the oddly evil Tucci.

It is a typical axiom in Hollywood that in the greatest love stories, the girl does not get the guy. Rick and Ilsa have to separate in Casablanca for the good of the western world, and death separates Jack and Rose as the Titanic mercifully sinks beneath the waves. But these losses are always in the interest of a greater loss that the audience is asked to appreciate, like war or tragedy. In The Terminal, Zeta-Jones’s character Amelia simply walks away from the adorable Viktor Navorski (Hanks), even though he is the kindest, most devoted suitor imaginable, who builds elaborate, expensive fountains for her in the airport in two weeks (I told you this movie was unbelievable!!). Presumably, she does this only because of the “incredible sex” provided by her boyfriend. Viktor, who treats her with respect, loses her love.

Of course, true to secular Hollywood’s modus operandi, none of the characters in any of these movies seek God’s will in helping to find out who is best for them. None of them is portrayed as having religious conviction at all, though Spider-Man 2 does hint at Christian faith in some of its characters in just the whispers that the first Spider-Man movie did. None even address fully the Biblical notion of virtue as criterion for soul-mate selection, and, conversely, all three value sexual compatibility too highly on the scale of conditions affecting marriage.

But even with these serious deficiencies, there is something to be said for a glimmer that Hollywood recognizes hard work as part of love and choice between two attractive loves as part of the very human side of romance.