The Hours (Stephen Daldry, 2002)

Critics often speak of the layers of a film, but I don’t believe I’ve ever understood what they were talking about until I saw The Hours. The more one thinks about its themes, the more connections one makes with life, art, people, and literature. The experience is like that of digging into a mine of meanings, and being more and more rewarded with richer veins of ideas the deeper one goes.

This is not to say that The Hours is a picture that portrays reality in all its fullness. For a Christian, whole crucial elements of life as it is in a universe where God exists, creates, and redeems are completely absent. No one in the film goes to church, no one professes faith, no one even seems a likely candidate to profess faith, if the subject were brought up. There is but one reference to the transcendent in the film, and that is in a sarcastic mention of omens. Everything in the film rotates around the human condition, and in portraying that, it has no peer. The film renders almost perfectly the alienation humanity suffers in a world without significance, the loneliness and separation felt by the best and the brightest—in this film, the “poet… the visionary”—who, as one of the main characters, says “has to die in order that the rest of us should value life more.”

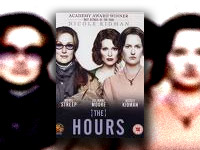

The Hours, to put it mildly, is not easily categorized. The film is structured as three separate but parallel stories, connected by the relationship three separate women have to Virginia Woolf’s novel, Mrs. Dalloway. After a brief opening in which we see Woolf, played in an Academy Award winning performance by Nicole Kidman, commit suicide by walking into the river Ouse, the film moves back and forth between single days in the lives of the women: Woolf herself in 1923, a housewife named Laura Brown in 1951, and Clarissa Vaughan, an editor living in New York in 2001. Woolf, living in Richmond, England, feels trapped by the boring, sterile life of the suburbs. Brown is similarly distraught by her existence as a mother and housewife in the “perfect” life of 1950s Los Angeles. Vaughan, in contrast, lives in bustling Manhattan, but has the same feelings of distress brought on by what she perceives to be the triviality of much of her existence.

This variation of both time and place, while unifying the stories by the similar theme of alienation, supported by comparable characteristics of each woman’s life like the difficulty in their spousal relationships, their explorations of homosexuality, and the angst each feels in making decisions, makes the film a deeply philosophical one. Hours explores the idea of a single day encapsuling all of life; as Woolf puts it in musing about her heroine, “Just one day… and in that day her whole life.”

But this movie is anything but a pure, philosophical abstraction. With massive complexity and verisimilitude to life, the characters are fully drawn by the script and the magnificent actresses who portray them. Kidman’s performance, though tragically overshadowed in the press by far too much discussion of a prosthetic nose she wears to simulate the noble, but tortured, features of Virginia Woolf, pounds discomfort and anxiety into the audience’s perception of this sad woman as she struggles with her genius and her madness. Julianne Moore is brilliant as the ultimate foil in the film, the beleaguered and cowardly (though the film makes no moral judgment of her decisions) Laura Brown who abandons husband and children because she is unable to bear the sterility of her existence. Meryl Streep plays Clarissa Vaughan as the piteous worrier she is, desiring to feel significant but too overcome by past regrets and present feelings to find the meaning she seeks by finding a way “always to look life in the face, and to know it for what it is, to love it for what it is. And then to put it away.”

These words, the final voice-over from Virginia Woolf’s suicide note to her husband Leonard which we hear as the film concludes, summarize its view of life. Life can be lived, but only with the realization that it has no ultimate significance, and for those who are not able to live with that fact “it is possible to die”. The poet, the visionary—in The Hours Woolf and the poet Richard, friend of Clarissa’s—is driven to suicide just because his gift for that which most mocks man’s meaningless existence, art, forces them to confront regularly the disconnect between the apparent nobility and value of man and his actual hollowness.

What a true tragedy this film is. Though its distributors put on a desperate campaign to convince potential audiences through its trailers that The Hours was an affirmation of life, the movie seethes and roils, tosses and turns through the lives of three dejected and agitated women, all of whom either contemplate suicide, fail at attempting suicide or actually carry it out. All three are lesbians, but this is almost extraneous to their stories and only highlights their sense of not belonging in the world. At its deepest level, The Hours is a study of life lived from hour to hour in fear and anxiety that man will never find rest, never be at ease in the world as he or she know it. What could be more tragic in a world we know to be significant because He is.