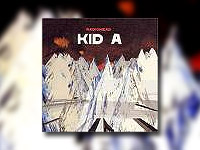

Radiohead, Kid A (2000)

Radiohead’s long-anticipated record, Kid A (2000) is the antidote to the Disneyfied-saccharine-commodification of pop and the misogynist-angry-victimization of hip hop. Instead, Kid A is a cerebral rock experience. Here is a rock album for the honest person who eschews numbing feelings, abandoning thought, and playing the victim. David Cheal writes in the London Telegraph that “Radiohead are pop stars who prefer to spend their time thinking about stuff than showing their bottoms to the paparazzi in the south of France.” Lead singer Thom Yorke puts it bluntly: “If you want to be entertained, go and see Hanson.” Radiohead is the thinking person’s rock group. Film actor Brad Pitt has called Radiohead “the Kafka and the Beckett of our generation.” And while Kid A is a marked contrast to their previous alternative rock albums, it remains infused with the same personal authenticity and artistic integrity that has given Radiohead a near cult-like following on both sides of the Atlantic.

Radiohead is a five-person group from Oxford, England. They met at a private boys school in Abingdon, a suburb of Oxford, and in 1987 formed a group called On A Friday. The band was put on hold as they finished their college education at such prestigious universities as Cambridge, Exeter, and Liverpool Polytechnic. Early in 1991, they regrouped in Oxford, cut a deal with EMI Records, and changed their name to Radiohead (after a Talking Heads’ song). Their first three albums met with increasing success: Pablo Honey (1992), The Bends (1995), and OK Computer (1997). OK Computer won the band a Grammy Award for Best Alternative Rock Performance in 1998.

Kid A defies easy description. It is best described as a deeply personal reflection on the state of one’s heart in the midst of a postmodern world. The music conjures a world blurred and out of focus. Newsweek called the album, with perhaps a little too much whimsy, a “sure winner for the ‘Lie in Bed, Stare at the Ceiling, Contemplate Life’ Album Award.” The sense of the album is one of isolation and despair, tension without resolution. The words are loosely littered throughout the musical score like the fragmented musings of one’s own agitated stream-of-consciousness: “Yesterday I woke up sucking a lemon,” “What’s going on?” “Vultures circling the dead,” “Who’s in a bunker,” and “It’s not like the movies, they feed us little white lies.” Kid A raises questions and emotions about one’s place in the world that we have made.

Every cultural artifact serves as the answer to an unspoken question. Linguist Kenneth Burke suggests that a cultural text like Kid A is best understood as a symbolic act, what he calls a “situation strategy.” A cultural text is the answer to a question, problem, or crisis. It is the listener’s responsibility to uncover the question or situation being addressed by the text. Burke writes, “We are reminded that every document bequeathed us by history must be treated as a strategy for encompassing a situation. Thus, when considering some document like the American Constitution, we shall be automatically warned not to consider it in isolation, but as the answer or rejoinder to assertions current in the situation in which it arose.”

What is the question that Kid A addresses? Perhaps the title itself gives us a clue. “Kid A” is a reference to genetic engineering. This album is a poetic message and warning to “Kid A,” the first cloned human embryo —like the sheep Dolly before him. Like Puritan poet Anne Bradstreet’s “Letter to an Unborn Child,” Kid A is a musical message to the first test tube boy as he comes to terms with his own history and the brave new world that begat him. The child awakes to a world where everything seems to be in its right place, and yet no one seems to know the answer to what is going on. Thom Yorke moans, “The lights are on but nobody’s home.” Everyone is walking, but to where? Only death seems real. The album ends with the line “I will see you in the next life.” Life from the test tube to oblivion seems inevitable, but also inconceivable. And so Radiohead captures the feeling of confusion that comes from being born into such a meaningless world.

Christians are frequently too quick to give answers. Unless we can identify with a modern seeker’s sense of meaninglessness out of our own life experience or out of empathetic reflection, our answers to their deepest longings will seem trite and sentimental. Theologian John Dominic Crossan captures this feeling when he suggested that for the postmodern person, “There is no lighthouse keeper. There is no lighthouse. There is no dry land. There are only people living on rafts made from their own imaginations.” Kid A, like Nine Inch Nail’s The Fragile, captures this feeling well.

That this seemingly enigmatic album has been met with commercial success bodes well for our culture. When questions are faced, answers are found. For spiritual sloth is the principal sin of our day. We live in an entertainment economy based on diversion and studied indifference. Fame, fortune, and fashion are the white lies of pop culture that prove empty in real life. Radio-head’s Kid A is mood music for facing the inevitable holes in one’s soul. It’s the right place to begin.

And for those who would love those who are still seeking, there is no better way than through music to capture again the feelings of emptiness that can now be filled with God’s love. Let God break our hearts once more for those who still live with the unanswered reality of their questions. “Kid A” is the postmodern Adam—a genetic orphan born into a world that no longer seeks its true home.

Radiohead’s message is that the longings still remain.