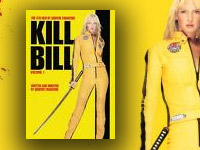

Kill Bill (Quentin Tarantino, 2003)

Revenge is a dish best served cold. – Klingon proverb

In April 2004, Paul Dergarabedian, president of Exhibitor Relations, a company which tracks movie ticket sales, was quoted in the New York Times, noting the success of the numerous revenge films then playing. “Vengeance rules at the box office,” he said. “You’ve got Walking Tall, The Punisher, Kill Bill. Moviegoers like these vengeance movies, but it has to do with the supply of movies as well. There’s a lot of them to choose from.” Since that time add in the Denzel Washington movie Man on Fire and the Mel Gibson-produced Paparazzi, among others, and it becomes clear that revenge movies have suddenly exploded onto our screens.

Chief among the current spate of revenge films is certainly the latest in the Quentin Tarantino oeuvre of bloody crime and action pictures, Kill Bill. Bill was released as two separate movies, and both parts need to be seen to grasp the full import of what Tarantino is trying to do. Kill Bill, Volume 1 is an action/adventure movie, heavily dependent for its inspiration on Hong Kong kung fu and samurai movies and television programs. Providing just enough plot detail to make the film coherent, the violent action assaults the viewer non-stop. Lathered in blood and dismemberment, scene after scene portray battles between a character known (for most of both movies) simply as The Bride and opponents who are determined to challenge her crown as “the deadliest woman in the world.” Using swords, knives, axes, chains, buzz saws, shotguns, AK-47s, uzis, machine guns, snakes, clubs, shovels and just about anything else that can wield death and destruction, The Bride and her opponents wage war in probably the most highly choreographed movie of mayhem ever made in America.

The second movie follows The Bride on her path of revenge as she seeks retribution for her daughter’s death, and her own attempted murder, at the hands of the Deadly Viper Assassination Squad, headed by her former lover—the baddie of all baddies—a character simply named Bill. The Squad, made up of world-hopping assassins among whom The Bride used to be numbered, show up at her wedding in a small, desert Texas town, to which she has escaped when she found out she was pregnant. Brutally murdering everyone there, they leave her for dead, not knowing that The Bride (played by Uma Thurman, a favorite actress of Tarantino’s) is only in a coma, out of which she suddenly awakens four years after the massacre. With fierce revenge on her mind, The Bride follows the now disbanded squad to their present locales, from that of suburban housewife in sunny Pasadena to a head yakuza of the Japanese underworld. In Bill 1, she finds and kills two of the Squad, leaving two more, and Bill, to find and kill in the second movie.

Kill Bill, Volume 2, though, spends much more of its footage in close-up dialogue, the various characters discussing revenge and death, yes, but also parenthood, change, motivation and goodness. Surprisingly believable, Beatrix Kiddo (the real name of The Bride) and Bill become likeable characters, caught in a maze of revenge and its consequences, which both of them are attempting to escape. At one point, as Beatrix flies to meet another of her adversaries, a voice-over of Hattori Hanzo, her mentor and maker of the finest samurai swords in the world, wistfully describes revenge as “…never a straight line. It’s a forest. And like a forest it’s easy to lose your way, to get lost, to forget where you came in.”

For those who would analyze Tarantino’s films for their contribution to the realm of cultural ideas, a difficulty arises from the complex interweaving of campy humor, realistic gore, movie homage and believable characterization one finds in them. One envisions a self-righteous protest that this is just a movie after all, if discussion were to start about the movie’s justification of revenge. Equally, however, the movie uses all the tricks of the trade to reach beyond itself to a deeper, philosophical meaning, laying bare the wounds of our existence and what Tarantino can only perceive as its twisted, convoluted reality. When Beatrix has come out of the coma and lies in the back of her getaway truck, willing her legs to begin working, she muses, “When fortune smiles on something as violent and ugly as revenge, it seems proof like no other that not only does God exist, you’re doing His will.” In the final shot of the movie, a bird’s eye view of her lying on the bathroom floor, alternately laughing and crying with relief as she hugs her daughter’s teddy bear, she repeats over and over again, the simple words, “Thank you, thank you, thank you.” Because she, as mother, has eliminated Bill and all the others, is she then justified in God’s eyes? Is her revenge, with all its lawlessness, violence and mayhem, okay because it is done in the name of a mother’s love for her child?

It would seem that some Christians would answer “Yes,” if the Mel Gibson-produced Paparazzi has anything to say about it. In this story, an actor (Bo Laramie, played by Cole Hauser) who has been thrust into stardom encounters four photographers who make his life miserable, and he decides to take matters into his own hands, plotting their murders and/or incarceration. Granted, the paparazzi cause a car accident that puts his son in a coma and injures his wife; they are clearly types whose moral character could not be more lacking. But is the answer to their unrepentant and unpunished evil really a lawless perpetration of evil in kind? Laramie does not just kill the paparazzi. He drops one off a cliff, sets up another to be brutally murdered by police in a hail of gunfire, bludgeons the third to death with a baseball bat (from behind no less), and frames the fourth for the bludgeoning. All this time, the police suspect, but act in regard to Laramie, equivocally at best, and complicitly at worst; they have, after all, seen The Untouchables and The Godfather, too.

The whole thing is blessed by Mel Gibson, who doesn’t just produce the film, staying safely in the corporate background, but appears in it in a humorous cameo. The movie clearly commends its main character’s behavior. No sooner is the last paparazzi disposed of, than the son wakes up, and the movie, like Kill Bill, ends with an approving scene, this time of the happy family hugging each other in a hospital room. The main character has a hit on his hands, a loving wife and child, a house that is safe again, and, perhaps best of all, a clear conscience, because his three murders and illegal frame-up were all done in the name of defending his family.

Some recent revenge movies have a self-sacrificial element to them, but most of them indulge in a “you-can-have-it-all” mentality, advocating a revenge that clears the mind, satisfies the soul and gets rid of a lot of scum in the process. The idea is not new to the movies; the Paul Kersey character, played so famously by Charles Bronson through the seventies and eighties in the Death Wish movies, comes to mind. And there are recent movies, like In the Bedroom and Mystic River, which sensitively explore the consequences of murderous revenge, showing it to be fraught with peril and guilt.

So what is the Christian to make of revenge? A simple “it’s wrong” does not do justice to Biblical stories like that of Jael and Sisera, where the woman drives a stake through the general’s head and is praised for it in a song that is as grisly and retributive as the event itself (Judges 5:24-31). “The wicked will not stand in the judgment, nor sinners in the congregation of the righteous,” writes the psalmist; the speedy demise of those who do evil is an appropriate subject for prayer and praise throughout the Psalms. Doesn’t that make retribution, if the governing authorities are not going to exercise their God-given responsibility to see justice done, the duty of those who know the right?

No. The Bible regularly proclaims vengeance to be the provenance of God alone, and Paul makes a special point to reject revenge in favor of repaying evil with good. In a passage that largely quotes the Old Testament, showing the principle to be one that transcends the divide between Old and New Covenants, he writes: “Beloved, never avenge yourselves, but leave it to the wrath of God; for it is written, ‘Vengeance is mine, I will repay, says the Lord.’ No, ‘if your enemy is hungry, feed him; if he is thirsty, give him drink; for by so doing you will heap burning coals upon his head.’ Do not be overcome by evil, but overcome evil with good.” (Rom. 12:19-21).

If revenge were justifiable on our part, it would only be at the call of God to revenge His name, and even then one would have to have the surety of a Jael, who did what she did during a time of war, to know that the revenge was really God’s, albeit through human means. Nothing like that idea is found in the portrayals of vengeance seen in American revenge movies today. The actions of Bo Laramie and of Beatrix Kiddo are driven entirely by a blurred vision of “family honor” or “motherly instinct;” they take no account of the human consequences of their conduct, much less the divine ones. How do they know they won’t be arrested for their misdeeds? Where would their happy families be then? Of course, Tarantino’s killings all take place in an unreal world entirely devoid of police, but if Kill Bill is only a fantasy, then the question of meaning becomes especially pointed. What does this kind of “fantasy world” revenge have to teach those of us who live in a real world? Very little. That the movie is free of moral teaching probably suits Tarantino just fine, but then why does he pretend to be elaborating on high moral themes like motherhood, family and honor? That is having your cake and eating it, too. Better not to serve the dish of revenge at all, but to forgive, as the Scripture enjoins us.