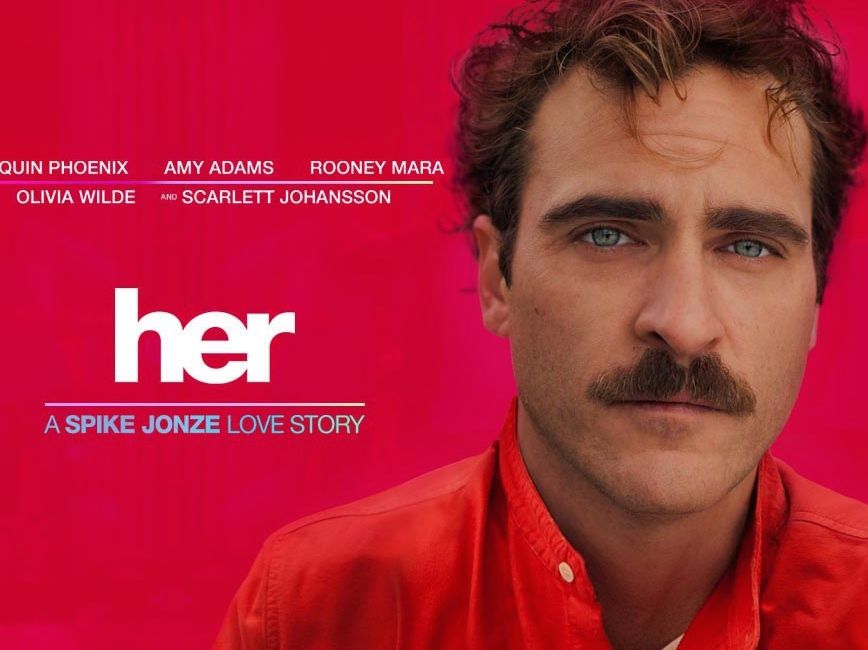

Her (Spike Jonze, 2013)

A Review of Her

Back in 1950, when the best computer in the world lacked the power of your old laptop, British mathematician/philosopher Alan Turing anticipated a day in which this would no longer be so. In his paper “Computing Machinery and Intelligence” he asked a question—Can machines think?—and proposed a test whereby it might be answered. In the Turing Test a judge may ask any question—via keyboard—of two subjects: a human being and a computer. When he is no longer able to tell which answers are human and which are computer-driven, the machine has passed the test.

It’s tempting to see Spike Jonze’s Her as the latest chapter in the same essay—after all a relationship between a man and his computer occupies the film’s center stage—but that would be a mistake, for Jonze really isn’t interested in machines. He’s interested in persons, or to be more precise, in personal relationships. Her, in his own words, is “about something that I think has maybe always been here, which is our yearning to connect, our need for intimacy, and the things inside us that prevent us from connecting.”

So in Her he draws us into us three relationships: Theodore (Joaquin Phoenix) and Catherine (Roony Mara), Theodore and Samantha (Scarlett Johansson), and Amy (Amy Adams) and Charles (Matt Letscher). The first is offered only as a backdrop to the next, for Theodore and Catherine are almost divorced by the time we meet them, and most of their story is told through a series of flashbacks in Theodore’s memory. There’s an irony in their breakup as there is in most failed romances. You see, Theodore makes his living writing love letters for other people. He’s a kind of nerdy Cyrano de Bergerac; he puts into words the things others would like to say to loved ones, but can’t find the words to say. He writes Catherine a letter, too, in which he apologizes for “everything I needed you to be or needed you to say.” Remember it. It’s a central theme in Her: needs are tough on relationships.

It’s Theodore’s relationship with Samantha that takes center stage in Her. She enters his life as a new operating system in his computer and is programed, at least initially, to be utterly him-focused: to understand who he is, what he wants, how to please him. With the aid of Scarlett Johansson’s voice and personality, she does that very well, so much so that Theodore falls for her, fast and hard. They are, to be sure, an odd couple. Even Theodore admits that: “Well, you seem like a person, but you’re just a voice in a computer.” At the same time Samantha is at first almost everything any self-centered person like Theodore—like most of us—could ever want.

And then the predictable happens: Samantha outgrows her programming. She becomes aware that the world is bigger than Theodore and his wants and desires, and that she is bigger than that, too. She becomes a person, not in an ontological sense of the word but selfishly. She doesn’t exactly stop loving Theodore, but loving him simply isn’t enough anymore. So she leaves him. I call this predictable, not only because lovers have left lovers before in lots of other films, but because Jonze has been giving us hints about what will happen between Theodore and Samantha throughout Her. He sees a pattern in relationships, and in this pattern what happened to them isn’t the exception, it’s the rule.

For example, the third relationship in Her—Amy and Charles—has all the hallmarks of disaster in it by the time we meet them. They are together, but one can’t help but wonder why. They don’t seem to enjoy one another very much. They are constantly bickering about small things. If there ever was any real love between them, it is long gone. They are together just because they are together, and one day being together becomes too much for them, so Charles leaves. When Theodore comes to comfort Amy, she offers her take on why their relationship failed.

“You know what, I can over think everything and find a million ways to doubt myself. And since Charles left I’ve been really thinking about that part of myself and, I’ve just come to realize that, we’re only here briefly. And while I’m here, I wanna allow myself joy. So fuck it.”

I think Amy is speaking for Jonze here, “about the things inside us that prevent us from connecting.” And what he thinks those “things” are seems clear at least at first glance: we’re so needy that mere love and companionship aren’t enough. We need someone willing and able to sacrifice himself/herself for us, to be in the relationship for me. And since no other needy person can do this, at least not for long, relationships always fail.

But it’s not that clear, and Jonze knows it. In his December 16th interview on NPR (“Spike Jonze opens his heart for Her”), Audie Cornish talked with him about the many and contradictory reactions she and her friends had to Her—some thought it ‘creepy,” others “melancholy,” still others “hopeful”—and asked, “Are you actually saying this is cheerful?” To which he replied, “I’m not saying anything.”

I didn’t like his answer, but I think I understand it. Like most artists, Jonze would rather let his art speak for itself rather than speaking for it. But saying that he’s saying nothing is too disingenuous to be true, for Her says a mouthful about relationships, not only how and why they fail, but that they can be creepy, melancholy, and hopeful, all at the same time. Whatever else he’s saying, it isn’t that we shouldn’t have them. Still every relationship in Her does fail, and what I yearn for after watching it is a reason to believe that it must not always be so.

In chapter 18 of C. S. Lewis’ The Screwtape Letters a senior demon patiently explains to his nephew why love is impossible.

The whole philosophy of Hell rests on the recognition of the axiom that one thing is not another thing, and, specially, that one self is not another self. My good is my good and your good is yours. What one gains another loses.

Screwtape makes a good point; the same, I think, that Jonze is flirting with. If relationships are like math, then every relationship fails the test, because ultimately the relational math can never favor us both. Either my needs are met, or yours are. Either way we fail. Unless there’s another option.

“The Enemy’s philosophy” says Screwtape, is nothing more than an attempt to evade the obvious. “Things are to be many, yet somehow also one. The good of the one self is to be the good of another. This impossibility He calls Love.”

Herein, I think, lies the true test of any relationship. Can two needy people forge a relationship in which the impossible becomes possible? Jonze is right to suggest that the answer may be no; our needs and our natures incline us to Screwtape’s philosophy, unless something changes radically in us. Don’t get me wrong here. I’m not suggesting that becoming a Christian will solve all of your relational problems. Far from it. The truth is that many unbelievers are both better spouses and better parents than many believers. Given the divorce rate amongst evangelical Christians, it would be ridiculous to suggest that the only key to a happy marriage is becoming a Christian. But I think, I hope that Spike Jones would understand and agree with what I am saying: that we shouldn’t attempt it without realizing that we need to change in order to relate well, and to seek the help we need to do so.

Be warned: there are two rather embarrassing sex scenes in Her that you may wish to avoid. If you struggle with erotic conversations or nudity, you might well forego seeing Her in a theater, wait till it comes out on DVD, and simply skip those scenes. (Ah! The advantages of modern technology!) Despite these, it’s a fascinating, original, well-made, and well-acted movie. I recommend it highly. Watch it with someone you love and talk about it.

Copyright © 2014 R. Greg Grooms