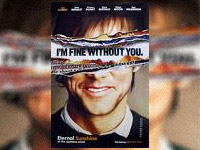

Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind (Michel Gondry, 2004)

Movies resist philosophical speculation. Experimental films like Alain Resnais’ Last Year at Marienbad, an attempt to write existentialism into film in the early sixties, suffer from the absence of the central element that makes movies so attractive: identification of the audience with characters and events that are portrayed on the screen. What we want is a story in which we can see ourselves as a participant.

The story of Marienbad had plenty of potential; its rough outline epitomizes the dramatic love story genre. A man and a woman in some exotic setting begin, and throughout the movie explore, their relationship, with the dramatic tension arising from the question of whether they will leave their spouses for each other. How many times have we seen variations on this theme? From Grand Hotel to Casablanca to Lost in Translation, the story of men and women comparing duty and desire in relationship is as old as story-telling.

Marienbad failed to attract a large audience, though it is still shown in film classes due to its experimental form. Marienbad’s sequences jump all over the place in time; its characters are not named; and every “fact” in the film is called into question so that the viewer never knows what is real and what isn’t. Finding it too hard to transfer themselves into the situations of either Madame A or Monsieur X, the audiences just said, “I’m outta here.”

I can’t help thinking about Marienbad as I think about Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind, directed by Frenchman Michael Gondry and written by American screenwriter Charlie Kaufman. The parallels are obvious. In Sunshine, Joel Barish (Jim Carrey) and Clementine Kruczynski (Kate Winslet) meet in a vacation spot and explore their relationship. Before long the viewer is treated to a complex structure of sequences that jump in and out of the historical narrative of the two main characters’ life together and the memories, and fantasies, of one of the characters. By the opening credits, it’s apparent that this movie is investigating something deeper than a simple love story, but the viewer has no clue what, and still isn’t sure by the end of the film. The difference between the films is that Sunshine has made almost 50% profit on its investment so far, and its run is not over. Though strange and philosophical, it is winning an audience.

The plot of Sunshine defies simple explanation. Joel and Clementine meet, fall in love, fall out of love, break up and decide to forget each other, in the end getting back together, wiser and more in love than ever (maybe). The key to the movie’s uniqueness, however, is the way they decide to forget each other. Kaufman introduces a bit of science fiction by having Clementine impulsively employ the services of Lacuna, Inc., a company that promises to erase memories of any relationship the client desires to forget. Joel finds out about this and decides to do the same thing to her, regretting the decision in the middle of the night-long process, and the fun begins.

As Joel fights the memory erasure, we move in and out of his sometimes conscious, sometimes unconscious dream-world, experiencing pieces of his life both with and without Clementine. Add in sub-plots concerning the Lacuna, Inc. employees, and the viewer’s head is on the verge of wildly spinning out of control.

Yet Kaufman’s script never allows this to happen. We are simply too engrossed in what is happening. Unlike the stories of Being John Malkovich and Adaptation, both of which Kaufman wrote, this story has too powerful a theme and is written too much with the heart to lose the viewer for long: love, even if it ends badly, is worth remembering. When love is gone, our memories of it are all we have. If we get rid of those, we get rid of ourselves.

The genius-level writing in this script is well-supported by Gondry’s sure-handed direction. Several reviewers have remarked at the particular excellence of the “procedure sequences,” often shot with a handheld camera in spotlight; they do have a remarkable feel of the real to them, even as things are happening on screen that are far outside the realm of human experience. Carrey and Winslet are brilliant; one hopes their performances will be remembered when Oscar time rolls around. The superb supporting cast made up of Tom Wilkinson as the conniving Dr. Mierzwiak and Mark Ruffalo, Elijah Wood and Kirsten Dunst as his assistants, is good enough to have carried the film themselves; everyone rises to the occasion.

The questions that Christians can ask of this film are endless. Far from presenting a hopeful, Christian notion of relationships, Joel and Clementine, though together at the end of the film, are not convinced that “this time it will work.” In fact, they explicitly agree that it probably won’t, but decide to give it a try anyway. Why? Is it desperation? Is it loneliness? Is it a belief that this is all there is, so we might as well make the best of it?

And what about the importance to the Christian of memory for relationship? God commands Israel regularly in the Old Testament to “remember” his faithful deliverance of them in history, particularly in the Exodus, but in many other instances as well. Jesus gave us the last supper as a remembrance of the great lengths to which he went to demonstrate his love for us. Memory plays a great part in keeping love aflame, and so it should. If love is a mixture of duty and desire, then memory is an aid to fanning the flames of desire, when duty is all that’s left. In Sunshine, duty in love is unimagined; love is all desire, and the characters seem resigned to this. For them, memory just becomes a way of coping with loss because when desire leaves, love is abandoned.

Lastly, perhaps most importantly, Sunshine shouts that the mind is a repository of what the heart has experienced; to erase its memories is to alter fundamentally who a person is and will be forever. God declares that he will remember us forever because he loves us so; can we allow our attempts at love to function any less faithfully?