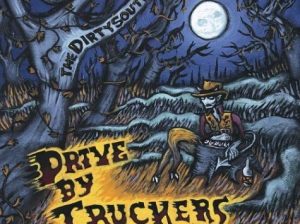

Drive By Truckers, The Dirty South (2004)

As I swing my Land Rover into the drive-through at Starbucks to order a Venti Nonfat Double-Cup Extra-Hot Two-Spenda Latté, a morning ritual after crew practice, I wonder about the relevance of the words I had read earlier in the day during my morning meditations by the swimming pool behind my condo. “Now listen, you rich people, weep and wail because of the misery that is coming upon you. Your wealth has rotted, and moths have eaten your clothes. Your gold and silver are corroded. Their corrosion will testify against you and eat your flesh like fire. You have hoarded wealth in these days. Look! The wages you failed to pay the workmen who mowed your fields are crying out against you. The cries of the harvesters have reached the ears of the Lord Almighty. You have lived on earth in luxury and self-indulgence. You have fattened youselves in the day of slaughter. You have condemned and murdered innocent men, who were not opposing you” (James 5:1-6). These are not the words of some firebrand Old Testament prophet. These are the words of James, Jesus’ half-brother, who reminds us that religion that God honors does not turn a blind eye to the widow or orphan—more specifically to those society abandons emotionally and economically.

Ironically, my bourgeois lifestyle (much as those discussed in David Brooks’ Bobos in Paradise: The New Upper Class and How They Got There) and my Christian suburbia North Dallas conscience was pricked by the authentic voices of a Southern rock ‘n’ rollers band and the stories told about The Dirty South. In the music and lyrics of Drive By Truckers the indictment of James finally came home.

Drive By Truckers are an Athens, Georgia band, who received wide recognition for their 2003 release, Decoration Day. Rolling Stone listed the album on the year’s 50 best, Spin listed it at #28 in their 40 best albums, and amazon.com picked as the #1 best alternative rock CDs of 2003. This August, DBT released their seventh album, The Dirty South. If unknown to rock aficionados, they won’t be unknown long. “It’s hard to find rock ‘n’ roll this tough, this serious anymore,” writes Steve Terrell in The New Mexican about the group. The Dirty South combines pulsing rock music with compelling storytelling—Southern history told from the perspective of the bad guy and outcast.

Here is where the album makes its distinctive contribution. It puts a human face on a social stereotype. Like William Faulkner’s depiction of the Bundrens and Snopes, the band uses Southern regionalism as a window on the universal longings of the human heart. The band has met with a larger following outside of the South. Earlier this summer, Howard Dean was widely criticized during the Democratic presidential primary by referring to “guys with Confederate flags on their pickup trucks” as legitimizing a Southern stereotype—a stereotype the New South would like to ignore. Rather than ignoring this culture, the Drive By Truckers punctures the stereotype by humanizing them. DBT speak with an accent that isn’t faked. They speak of a reality they have lived. Four of the five band members grew up in Muscle Shoals, Alabama and it was back in Muscle Shoals where the album was recorded at the FAME (Florence Alabama Music Enterprise).

Muscle Shoals is a small town in a dirt-poor part of northwestern Alabama. This is music from their veins about their blood. The Dirty South examines the back roads of the Deep South and paints a portrait of poverty, despair, and hopelessness—the faces of guilty anti-heroes. Here is a culture of victims who cry out against heartless politicians, corrupt law enforcement agents, greedy business executives, relentless natural disasters, callous Christian ministers, and skewed national priorities. “Their Dixieland has been decimated by outsourcing and downsizing, leaving good people to brew moonshine, sling dope, kill one another, or suffer in silence,” writes David Peisner in Maxim. The words of James—“You have condemned and murdered innocent men, who were not opposing you”—have a new context: Detroit automakers, Wal Mart retailers, TVA bureaucrats, and NASA scientists.

Tell me how to tell the difference

between what they tell me is the truth or a lie

Tell me why the ones who have so much

make the ones who don’t go mad

With the same skin stretched over their white bones

and the same jug in their hand

Songwriter and lead singer, Patterson Hood, told the Pittsburgh Tribune-Review, “Some people do some terrible things. But I wanted to try to understand why they do those kinds of things. I tried to take that point of view when writing about some of the unsavory characters that pop up on the record. I didn’t really want to say that ‘this is good’ and ‘this is bad.’ ‘Cause to me, the things they do speak for themselves.”

The last three DBT albums suggest a progression of analysis: Southern Rock Opera told the story of young adults who are told to go out and conquer the world and die; Decoration Day spoke of adults who make choices and now have to live with the consequences of their choices; and The Dirty South portrays a world where people don’t feel they have any choices anymore. Youthful dreams have given way to disillusionment and the fight for mere survival. “Many of the hard times being sung about in these songs have been replaced by even harder times,” the band explains on their web site. The logic of survival is laced with drugs, alcohol, and crime. For these folks time in the penitentiary is viewed as a vacation. Government reports indicate that rural teens are 83% more likely to use crack cocaine, 34% more likely to smoke marijuana and twice as likely to use amphetamines than teens in large cities.

We do well to remember that every statistic has a story. DBT’s Puttin’ People on the Moon tells the story of a Georgia autoworker who loses his job to an overseas plant, turns to selling drugs to make ends meet, unemployed and without health insurance his wife gets cancer from upstream industrial waste, without chemotherapy she dies, and he goes to work for Wal Mart cynical and broken by a life where every promise given has been a promise broken. He notes with biting irony that just down the road in Huntsville, they’re putting people on the moon.

Another Joker in the White House, said a change was comin’ round

But I’m still workin’ at The Wal-Mart and Mary Alice, in the ground

And all them politicians, they all lyin’ sacks of shit

They say better days upon us but I’m sucking left hind tit

And the preacher on the TV says it ain’t too late for me

But I bet he drives a Cadillac and I’m broke with some hungry mouths to feed

I wish I’z still an outlaw, was a better way of life

I could clothe and feed my family still have time to love my pretty wife

And if you say I’m being punished.

Ain’t he got better things to do?

Turnin’ mountains into oceans

Puttin’ people on the moon

The Dirty South depicts a culture of poverty, where “hope” has long since been removed from the social vocabulary. “The Lives of the Rich and Famous” is beamed by TV Satellite dishes to mobile home trailers where despair sucks the oxygen out of the room. “The central ideology of ‘mainstream culture,’ the belief system that most of us share, is liberal consumerism—a secular, individualist creed that essentially adds more shopping hours to the old exaltation of life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness,” writes William Finnegan in Cold New World: Growing Up in a Harder Country. “A new American class structure is being born—one that is harsher, in many ways, than the one it is replacing.” Economic inequality is coupled with cultural alienation and individual hopelessness. In “ Lookout Mountain,” a song about suicide, the singer hesitates as he wonders “Who’s gonna mow the cemetery when all of my family’s gone? Who will Mom and Daddy find to continue the family name?” DBT gives voice to this reality and these feelings. Here one finds haunting stories and hardened perspectives of lives we’d rather ignore.

We ain’t never gonna change.

We ain’t doin’ nothin’ wrong.

We ain’t never gonna change

so shut your mouth and play along.

You can throw me in the Colbert County jailhouse.

You can throw me off the Wilson Dam

but there ain’t much difference in the man I wanna be

and the man I really am.

We can warn against the self-fulfilling prophesy of playing the victim. But sometimes the voices of victims are real—their suffering undeniable.

A number of years ago I was asked to work with Daniel, a twelve-year-old sixth grader whose father had tried to kill his mother by running over her in the Ingle’s grocery store parking lot. When he failed he jumped out of the car and stabbed her with a knife until stopped by shoppers. This horrific crime was in the quiet rural community of Black Mountain, North Carolina, the home of Billy Graham. For weeks I met with Daniel in his mountainside dilapidated mobile home, read letters to him from his father in prison, talked about school and Pokéman. I’ve lost contact with Daniel. He would be sixteen or seventeen now. I wonder if he listens to Drive By Truckers. I wonder what difference it might have made if I had written to him over these past years. Is a handwritten note to a boy without a father like giving a cup of cold water in My name? These lives of quiet desperation will not be changed by social programs or presidential elections, but by the simple touch of another’s heart. Helen Keller is also from Muscle Shoals, Alabama. “ Although the world is full of suffering, it is full also of the overcoming of it,” she writes. Yet Helen Keller had Anne Sullivan. Few overcome suffering alone.