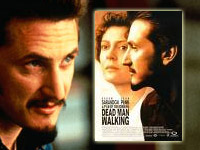

Dead Man Walking (Tim Robbins, 1995)

Dead Man Walking, the four-time Academy Award nominated film of writer and director Tim Robbins, deeply troubles the soul. It is a film that cannot be shaken easily.

Walking is the story of Sister Helen Prejean, played by Susan Sarandon, and the relationship she strikes up with a convicted killer named Matthew Poncelet, portrayed by Sean Penn. From death row at a Louisiana state prison, he writes her a letter asking for help, and, though she has never met him and knows nothing about him, she goes to visit him anyway and steps into a world with which she was up to that time totally unfamiliar—a world of unspeakably horrible crimes and boring legal procedures, of innocent victims and hardened criminals, of the pain and hatred of parents denied the joy of seeing their children reach maturity and the shame and sadness of a mother whose son is a murderer and rapist. Over this world hangs the uncertain cloud of execution by lethal injection for Poncelet; Sister Prejean in ministering to him can never forget how little time she has before he dies. The film focuses its attention on the relationship that these two people build in the face of his increasingly certain death.

The power of this film lies in just that fact, that Robbins does not slip into maudlin preaching about the evils of the death penalty or the inhumanity of prison life or any one of a thousand other “messages” he could have made this film about. Instead through a script that never departs from its center and through some of the finest performances ever achieved on screen by both the leads and the supporting cast, Walking shows us real human beings trying to find ways to muddle through a desperate, nightmarish situation. The fact that the film is based loosely on a true story (Sister Prejean is a real person, and Poncelet is a fictionalized composite of several death-row inmates she visited over a period of time. The crime in which one of them participated was very like the one portrayed in the movie.) with all the ambiguities of real life increases its dramatic intensity and creates much deeper conflict in the viewer than a more one-sided film would have.

Opposition to the death penalty often rests on the argument that it takes the life of an actual human being (“some mother’s son”), not an abstract “killer.” Support for it comes from the acknowledgment that that same person was capable of the most brutal and horrifying acts against innocent fellow human beings, and justice requires that he die for these acts. Both these arguments are made in the film with strength and grace as Sister Prejean visits time and again with both the killer and the parents of the dead couple, sympathizing with, and ministering to both groups. Though it seems clear that the film ultimately supports the abolition of the death penalty, the pain and humanity of the wronged parents is no less sensitively portrayed than that of the frightened, pitiful Poncelet, and this humanity is what pulls the viewer in such complex directions.

Surprisingly, the film does not avoid the spiritual issues that a nun in this situation would certainly address. Bible reading, recognition of sin and repentance for it, asking forgiveness and granting it—these are all central to the relationship between Sister Prejean and Matthew. Ultimately, though, spiritual matters are handled murkily at best and wrongly at worst. Repentance is defined as simply owning up to the sin that one has done; awareness that God graciously forgives that sin in Christ, while mentioned earlier in the film, is not acknowledged in the crucial scene when Poncelet confesses to Sister Prejean. In fact she declares him to be a son of God without his acknowledging God’s forgiveness at all. Sister Prejean consistently questions Matthew about his Bible reading and encourages him to “read about Jesus” but then proceeds to misinterpret John 8:32 (“The truth shall set you free”) in terms of a sappy, liberal theology. On the other hand, Poncelet does show fairly early on that he intellectually knows the gospel, and his later personal ownership of sin could be understood as a true “conversion” when viewed in the light of those earlier statements. Additionally, he displays a confidence about his eternal destiny after his last-minute confession, and his last words are ones of confession to, and sympathy for, the parents of the murdered boy and girl. Sister Prejean, when at the end of her strength, quite movingly calls out to Jesus for courage and help as she desperately beats her fists against the bathroom wall; this is not the typical portrayal of a cool, aloof, agnostic liberal. The spiritual content of the film should spark a lot of interesting discussion among Christians seeking role models for service in the films Hollywood is putting out these days.

The questions about Sister Prejean’s orthodoxy and the validity of Matthew Poncelet’s conversion pale in significance for the Christian, though, when confronted by the real issues presented in this moving account of a scared, weak servant of God who just wants to do what is right. She is willing to do that no matter what the cost to herself. Are we?