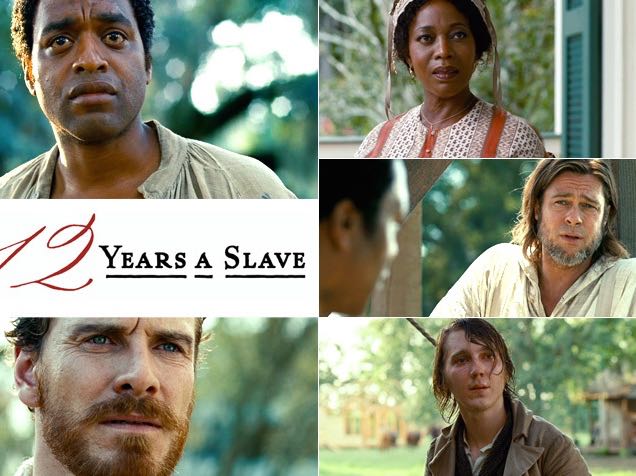

12 Years a Slave (Steve McQueen, 2013)

Denial, Desire, and the Proclamation of Scripture: Theological Reflections on 12 Years a Slave

Harriet Tubman, the former slave and leader of the Underground Railroad, once said, “I freed a thousand slaves and could have freed a thousand more if only they knew they were slaves.” This last clause, “…if only they knew they were slaves,” suggest that many slaves experienced a profound and damaging formation. That is, to convince a slave that she is not a slave would necessitate a host of subtle and powerful actions. These actions would need to shape human beings into thinking that they are something other than what they are, that their world is something other than it is. While Steve McQueen’s 12 Years a Slave does not take up the problem of convincing a slave she is not a slave, it does put on display some of these subtle and powerful actions. In this film, these actions aim to convince slaves that atrocities are merely ordinary life. In chronicling some of these formative actions, the story offers important points of reflection on Christian life, particularly our proclamation of Scripture.

12 Years a Slave chronicles the story of Solomon Northrup, a free black American who was unlawfully sold into slavery. The opening of the film brings Northrup’s free life into stark contrast with his slavery. The film’s first images are of a sugar cane field, and a white man instructs a group of slaves on the particulars of the harvest. In the midst of this slavery, Northrup remembers his past life. As a working musician, he remembers that his playing delighted audiences. As a husband and father, he remembers the affections of his wife and children. As a free man, he remembers the would-be circus performers who lured him to Washington D.C. with promised musical performances. As a black man, Northrup arrives at the capital, and white men capture him. He spends over a decade as a slave in Louisiana, many miles from home.

From Northrup’s emotional point of view, the film plunges the audience into a world turned upside down. It is a world where white persons not only inflict abuse and denigration on black persons, but it is also a world where whites describe those horrors to blacks as though they were nothing of the sort. Whites re-describe atrocities as everyday life.

In some cases, the film presents these re-descriptions as intentional, thoughtful, and complex. For example, early in Northrup’s detention, white men use fetters to force him into a submissive posture. Once in this posture, they beat his back with a large paddle. The beating tears Northrup’s shirt and stains it with his blood. Subsequently, one of his captors gives him a new shirt in an apparent act of graciousness, and in the exchange, the captor takes the torn, bloody one. Northrup protests, “No, no. That’s from my wife—,” but the white man interrupts, “Rags and tatters.” He waves the bloody shirt at Northup and exits the cell, “Rags and tatters.” While the violence aimed to procure submission from Northrup, his captors wove into that violence an ingenious and powerful mode of re-description. His shirt is not a gift from his wife. It is not an object with history or attachments. The shirt is not a shirt. It is re-described to him as, “Rags and tatters.” The implication is subtle but clear. Northrup is like the shirt. He has no wife, no history, no attachments. Northrup is not Northrup.

Other instances of re-description, however, are not intentional, but it is precisely their accidental character that makes them powerful. One key moment occurs early in Northrup’s enslavement. A man named Master Ford (Benedict Cumberbatch) purchases Northrup and another slave, Eliza (Adepero Oduye). The slave salesman (Paul Giamatti) refuses to sell Eliza’s children to Ford, and the separation affects Eliza. Upon arriving at Ford’s plantation, Ford’s wife, Mistress Ford (Liza J. Bennett) observes Eliza weeping. She says to her husband, “This one’s crying. Why is this one crying?” Ford responses matter-of-factly, not even mustering complete sentences, “Separated from her children. Couldn’t be helped.” The Mistress seems genuinely moved and attempts to comfort Eliza. “Something to eat. And rest,” she says, “Your children will soon be forgotten.” Mistress Ford does not grasp the searing irony her words. Her comfort can only function as comfort if the atrocity of divided families is ordinary. To be comforted, Eliza must accept these atrocities as no longer atrocities.

While the film is filled with countless examples of re-description, there are three moments of implicit re-description that involve scripture, and it is these sermons that might teach us something about our own proclamation of God’s word.

The first utterance of scripture occurs shortly after Northrup arrives on Ford’s plantation. Early in Northrup’s time under Ford’s ownership, an overseer named Tibeats (Paul Dano) inducts Northrup and a few other slaves into life under his authority. His first step is to sing a song called, “Run, Nigger, Run.” Slaves originally composed the song to warn of various dangers in an escape, dangers like paddy rollers—patrols that search the countryside for runaway slaves. When Tibeats sings it, he transforms the song into a degrading taunt. He dares them, “Run, nigger, run; da paddy-roller get ya. Run, nigger, run, well you better get away.” Throughout the day, the song accompanies Northrup’s work, as though it haunts his memory. They chop trees, and Northrup still hears Tibeats’ exaggerated squeals, “Some folks say a nigger don’t steal. I caught three in my cornfield. One has a bushel. One has a peck. One has a rope, it was hung around his neck.”

As their workday comes to a close, the images turn to Master Ford, but Tibeats’ singing continues from the previous scene. Ford’s body fills the screen. He stands before a white trellis covered in roses, and Tibeats’ voice accompanies, “Run, nigger, run.” Ford is dressed in clean clothes. They are a pale yellow and pink. Tibeats’ whispers, “The paddy roller get ya.” Ford calls, “I am the God of Abraham, and the God of Isaac, and the God of Jacob.” Tibeats’ responds, “Run, nigger, run, well you better get away.” In a wide shot, it becomes clear that Ford holds a Bible in his hand. His wife is seated to his left. An overseer sits to his right. Before him, slaves sit in rows that resemble pews. This is church. Ford, his wife, and his overseer are its leaders. The slaves are its congregation. Though Tibeats is physically absent, he is present in spirit. His song overshadows the entire proceeding.

While scripture and song occur simultaneously on the soundtrack, Northrup experiences both as distinguishable and connected. Ford speaks in the present, Tibeats in his immediate past. However, grounded in Northrup’s emotional point of view, the film presents both utterances as deeply related. When Northrup hears the covenantal name of God, he also hears, “Run, nigger, run.” When he hears the good news of Jesus, he also hears threats of violence. When he hears God’s word of life, he also hears words of death.

Ford soon offers a second sermon. After some time on the plantation, Eliza has not forgotten her children, and her crying persists, this time on a Sunday morning. As Eliza weeps publically, Ford says, “Whosoever therefore shall humble himself as this little child, the same is greatest in the kingdom of heaven. And whoso shall receive one such little child in my name receiveth me.” In response to Eliza’s public display, Mistress Ford frowns. She leans to her house slave and whispers, “I cannot have that kind of depression about.” Northrup overhears his mistress, and Ford continues as though Eliza is not crying. He preaches, “But whoso shall offend one of these little ones which believe in me, it were better for him that a millstone were hanged about his neck, and that he were drowned in the depth of the sea.” In the next scene, Mistress Ford makes good on her whispers. A white man and a slave forcibly remove Eliza from the plantation.

Like the previous sermon, Northrup hears simultaneous sounds as distinguishable and interpenetrating. In the simultaneity of scripture, crying, and whispers, the film expresses a profound irony. The biblical passage underscores the need for Christians to care for the weak, but Ford denies the weakness in their midst—Eliza’s tears. Furthermore, when Northrup hears Jesus’ concern for the weakest, he also hears his mistress’ words, words that despise Eliza’s weakness. When Northrup hears the good news of Jesus, he also hears denial and disgust. When he hears the word of life, he also hears words of death.

The third sermon occurs when Northrup’s second master, Edwin Epps (Michael Fassbender), speaks for the first time. Having recently acquired a new group of slaves, Northrup included, Epps stands on his porch and delivers a short homily. He reads, “And that servant, which knew his lord’s will, and prepared not himself, neither did according to his will, shall be beaten with many stripes.” He then offers a brief commentary, “That nigger that don’t obey his lord—that’s his master—d’ya see? That there nigger, ‘shall be beaten with many stripes.’ Now ‘many’ signifies a great many: 40, 100, 150 lashes.” Epps then raises the Bible in the air and concludes: “That’s scripture.”

While Epps’ misinterpretation is clear to us, it is important to notice that he intertwines good practices of biblical interpretation with his own desires. For example, Epps makes reasonable historical connections between the first century and his own moment. In the first century, the “lord” often referred to a man whose household included salves. Therefore, translating “lord” as “master” is not without warrant. In addition, he aligns his reading with the assumptions of the passage in question. Because lords had the right to beat their slaves, masters have that same right. Epps then goes on to ponder ambiguities in the text, particularly the phrase “many stripes.” I count these three practices—drawing a connection between the Bible’s history and our present moment, assuming what Scripture assumes, and attending to ambiguities of the text—as good practices Christians should perform. However, these practices do not rescue Epps from his own desires. He sees the truth of Scripture as internal to his socio-economic vision of flourishing, a vision that needs chattel slavery. As in the previous sermons, Northrup hears a word of life, but he also hears words of death.

These three sermons suggest the profound impact denial and desire can have in any proclamation of scripture. Ford reminds me that any sermon can deny the world in which it lives. When Ford stands before his congregation, he speaks as though atrocities do not exist. He speaks as though Tibeats’ words have no bearing on reality. He speaks as though Eliza does not cry. He speaks as though his wife does not abhor Eliza’s weakness. Through Ford’s denial, the gospel becomes another means of re-describing atrocity as ordinary life. The same possibility holds true for us. If we ignore the atrocities around us, we might unintentionally re-describe those atrocities as ordinary life. Something similar is at play in Epps’ sermon. Epps uses scripture’s authority to buttress his own authority. In so doing, he re-describes the atrocity of violence as gospel. It is entirely possible that good practices will not save us from our own misconstrued desires any more than they saved Epps.

The power of denial and desire suggests a strange but palpable theological reality about scripture and about Christ. The film suggests that words of scripture are vulnerable words. They are vulnerable to the denials and desires of those who preach them. Christians have often struggled with this reality, and we should not consider ourselves immune. But this reality points to deeper connection between scriptural vulnerability and the vulnerability of Jesus’ body. Humans coerced the Word, and the Word carried his own cross. Humans humiliated the Word, and the Word hung in shame upon a tree. Humans declared death over the Word, and the Word lay in a grave. If the Word’s flesh was this vulnerable, then it should be little surprise that scripture is also vulnerable. Scripture is so vulnerable that our denial and desires can make the word of life sound as though it is a word of death. This was certainly Northrup’s experience. I suspect Northrup is not alone.

Today, many of our churches may very well deny the atrocities that surround us, and in our denial, we may inadvertently use good biblical practices to support our own desires. In my church, I have observed something quite like this. I have never heard anyone in my church utter the word, “Ferguson.” Neither have I heard the names Michael Brown or Eric Garner spoken there. In a similar fashion, my church sits only a few miles from the murder of three persons in Chapel Hill, NC, two of which were Muslim women. To my knowledge, my church has offered no prayer or no words of mourning. It is as if, in our denial, our church might desire to see a world with little racial or religious atrocity, a world with little death and suffering. I suspect my church is not alone.

This observation requires massive qualifications. I do not mean to diminish God’s sovereignty or providence. Just the opposite—I know of no present church that affirms slavery as internal to Christian life. I count this reality as evidence of God’s providence to heal and correct the church. I also do not mean to insinuate that churches that have chosen to not talk about matters like Ferguson are somehow incapable of loving Jesus or believing in Scripture. They are not, on my account, excluded from God’s healing work. Rather, I only mean to suggest that the church is not immune to sin. Like our mothers and fathers in the faith, we are also tempted to confuse the injustice of humanity for the justice of God, to mistake the City of Man for the City of God, to misunderstand words of death for the word of life.

In the midst of these temptations, I can think of no hope besides Jesus’ body. Though Jesus’ flesh was vulnerable unto death, beyond death stood resurrection. 12 Years a Slave has convinced me that resurrection is the church’s only hope. It is only by the power of Spirit—the Lord and giver of life—that our proclamation of the word of life can be for us words of life.

Copyright © 2015 Naaman Wood