Art / Movies / Spirituality

Evil Depicted in Breaking Bad and Mad Men

What’s happened to you?

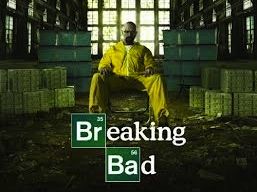

In one of the most stunning scenes in AMC’s Breaking Bad protagonist Walter White explains to his wife why he isn’t in over his head as a manufacturer of methamphetamine, working in the hardened, dangerous world of the Mexican cartels and drug trade.

Who are you talking to right now? Who is it you think you see? Do you know how much I make a year? I mean, even if I told you, you wouldn’t believe it. Do you know what would happen if I suddenly decided to stop going in to work? A business big enough that it could be listed on the NASDAQ goes belly up. It disappears. It ceases to exist without me. No, you clearly don’t know who you’re talking to. So let me clue you in. I am not in danger, Skyler. I am the danger. A guy opens his door and gets shot and you think that of me? No. I am the one who knocks.

It’s a positively chilling scene that provides all the proof needed for Bryan Cranston’s Emmy credentials. And it’s a scene that shows what makes Breaking Bad more than just a phenomenal TV show, but a TV show that deserves a wider viewing amongst discerning Christians.

Stories are formative, that’s where we have to begin. A good story doesn’t just—or even primarily—entertain or enlighten. It shapes us. I was a different person after reading Hugo’s Les Miserables then I was before. The same goes for Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings and Rowling’s Harry Potter books. This is a point Jamie Smith makes very well in his Desiring the Kingdom. Human beings aren’t primarily thinkers or even believers, but desirers and story is one of the chief players in shaping our desires. This insight also provoked C. S. Lewis to write The Abolition of Man in which he discussed the need for “men with chests,” which was his shorthand for human beings with the intellectual ability and personal maturity to balance the rationality of the head and the visceral appetites of the stomach.

So in deciding to take in a story—be it a TV show, a movie, or a book—one of the first questions Christians ought to ask is not necessarily whether the movie has profanities in it or if it has lots of violence. Those are worthwhile questions, but not first questions. One of the biggest question to ask is in what ways will this story, based on whatever I know about it, shape my heart? Obviously there are other questions. One of special importance for readers of Critique is what this story tells us about the storyteller as well as the people hearing the story. Consequently, many of us choose to see a movie like Pulp Fiction, even though it lacks the sort of redemptive themes present in the Christian story. It’s a worthwhile movie to see in order to be conversant with our neighbors. (Plus one can’t deny the pleasure to be gained from watching a master like director Quentin Tarantino at work.)

Many of us will also choose to watch a show like Mad Men, AMC’s other runaway hit, for similar reasons. The costumes and scenery of the show are stunning, the writing is top-notch and there’s a great deal to learn about our culture and ourselves from spending an hour with Don Draper and company. Mad Men can be a ton of fun. But many of us will choose not to watch Mad Men (or Pulp Fiction) for reasons a friend of mine summed up well when he said Mad Men was too decadent. The prophets warn us against those who confuse good for evil and it’s hard to deny that Mad Men protagonist Don Draper does exactly that. Draper is neglectful of his family, almost pathologically selfish, and a sometimes-boorish alcoholic. And yet almost every man who has watched the show admits to feeling some distant (or not-so-distant) desire to be Don Draper: The suave, in-control salesmen with an impeccable sense of style. The show’s sheen—the glitzy settings and clothes, the impeccable writing, the bigness of the characters—can make being good seem so utterly boring and blasé. Indulging every desire, meanwhile, becomes the gateway to freedom.

Put another way: A show like Mad Men isn’t guaranteed to do harm to your heart and mind, but it does have a way of making sin appear attractive and redemption unreachable. It’s a deeply seductive tale with an ability to subconsciously transform the viewer in unhealthy ways. Simply put, it probably fails the portraying evil as good test. That’s not a definitive argument against watching Mad Men, but it is an argument for watching it with a great deal of thought and intentionality.

And that brings us back to Breaking Bad. On the surface, Breaking Bad looks very like it’s fellow AMC hit Mad Men. Both are shot beautifully, both feature excellent acting, a bleak storyline and a certain tendency toward the seedier aspects of life. But as Chuck Klosterman wrote for Grantland last year, “Breaking Bad is not a situation in which the characters’ morality is static or contradictory or colored by the time frame; instead, it suggests that morality is continually a personal choice… The central question on Breaking Bad is this: What makes a man ‘bad’ — his actions, his motives, or his conscious decision to be a bad person?”

When the series begins, the show’s protagonist, Walter White, is a middle-aged high-school chemistry teacher enduring a job he doesn’t especially like because it’s the best way he can provide for the family he loves so much. In the pilot, he discovers that he has stage III lung cancer and, desperate to provide for his family, decides to start manufacturing methamphetamine to create a nest egg. Initially, his goal is to make about $750,000; enough to cover the mortgage, college for both his kids and to cover any other major expenses that might arise over the next 20 years.

But as the series moves forward, Walt develops a taste for the danger of the drug trade. More importantly, the pride that had always been suppressed under a thin veneer of suburban respectability bubbles to the surface and over four seasons perverts him into a, forgive the cliché, cold-blooded killer who looks very like the men he most feared in season one. Quoting Klosterman, “[Walt’s change is] a product of his own consciousness. He changed himself. At some point, he decided to become bad, and that’s what matters.”

After I finished the second season of Breaking Bad, I revisited C.S. Lewis’ masterful chapter in Mere Christianity titled “The Great Sin.” It’s Lewis’ exploration of pride and if seeing Walter White’s downfall doesn’t provoke in you a deep fear of pride, nothing will.

The drama of the show comes from watching Walter’s transformation from a frustrated middle-class American male to the drug kingpin he becomes only a year later (in the show’s chronology). But unlike so many other shows, movies and novels with morally ambiguous heroes—think Llewelyn Moss in No Country for Old Men, the aforementioned Don Draper, Christopher Nolan’s Batman, or Kevin Spacey’s Lester Burnham in American Beauty—Breaking Bad is much more willing to show its protagonist in a stark and uncompromising light. Draper’s foibles and failings are dismissed as a product of the 1960s, Moss is a basically good family man just trying to protect his family, Burnham, meanwhile, is simply reacting against the tedium of life in cubicle land, circa 1999.

What’s fascinating with Breaking Bad is that creator Vince Gilligan could use similar devices to explain away Walt’s behavior. He’s a family man doing whatever he can to provide for his wife and kids just like Moss; he’s a talented man who feels trapped and confined by a lifeless, tedious work environment and a staid, predictable suburban life, just like Burnham. He could even be seen as a product of post-recession economic fears, a product of his time just like Draper. All the factors that make us cautiously sympathetic to those characters are in play on one level or another with White. In fact, Skyler makes precisely that point just before Walt’s speech: He’s a good person who’s just in over his head.

But Gilligan eschews them all. What we’re left with is a grizzly, disturbing picture of human evil when all the pretense and justifications are stripped away. Walt’s “I am the one who knocks” speech is legendary, but not because it makes us more sympathetic to him. It’s not Lester smashing the plate against the wall or Llewelyn telling Chigurh he’ll be after him—scenes showing a character’s descent, but doing so in a sympathetic light. Rather, it’s the cue to us—and Walt’s wife—that we’re dealing with a radically new person. He’s no longer the frustrated, somewhat bumbling and basically good genius of season one. He’s changed and we’re encouraged to look at him the way Diane Keaton looks at Al Pacino at the end of The Godfather: “What’s happened to you?” It’s a mixture of horror, deep regret, and a pinch of revulsion.

In other words, we’re encouraged to think of an evil character as an evil character. Walt will always have some level of empathy because we remember who he was and why he got into the drug trade in the first place. He’ll never be a true villain. But he is a thoroughly deconstructed anti-hero, an anti-hero whose failings are viewed as real failings and not as a variation of heroism. Breaking Bad may be grittier than Mad Men and it may favor a much saltier kind of language, but on this basic level the show is much closer to the Christian story than the moral quagmire of ambiguity that characterizes every character in Mad Men.

Copyright © 2012 Jake Meador