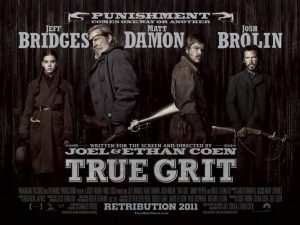

True Grit (Coen Brothers, 2011)

Joel and Ethan Coen cannot seem to do any wrong nowadays. In 2008 they won the Academy Award for Best Picture with their astounding adaptation of Cormac McCarthy’s No Country for Old Men. In 2009 they finally issued a life-long dream project, the semi-autobiographical A Serious Man. While no box office hit, Man was a critical darling with its hilarious and poignant absurdist take on Jewish angst and growing up in the sixties. This past year was supposed to be a sort of “year off”; they made a movie they had wanted to make for some time, but did not expect it to raise much interest or even be that successful at the box office. Even though True Grit had star power in the likes of Academy Award winners Jeff Bridges and Matt Damon, the film was a Western and was to be carried largely by a fourteen year old girl, Hailee Steinfeld, who was unknown.

The Coen brothers are great filmmakers, but lousy prophets. True Grit took the box office by storm, making $247M worldwide on a budget of $38M, and was nominated for 10 Academy Awards, surprising almost everyone including the brothers themselves. No Western has made significant inroads on the American movie scene since 1992’s Unforgiven, and at the time, Unforgiven was the first western to make critical and popular noise since the Sixties. Grit garnered an unheard-of 96% rating among critics and 86% audience popularity rating, as measured by rottentomatoes.com. What is going on? How does a movie that even its makers were not certain of become such an amazing success at all levels?

Answers to that question lie in many places, but one is that the movie, like many of the nominees for Best Picture this year, rode a simple, but thoughtful, story to its success. Packed with ideas about justice, revenge and honor, Grit chronicles the maturing of Mattie Ross, a frontier girl determined—and I do mean determined—to see her father’s death avenged. She hires Rooster Cogburn, a U.S. Marshall, moonlighting as a bounty hunter, to help her track down Tom Chaney, her father’s killer, in the Indian territory of Oklahoma. She arranges her father’s funeral, negotiates the sale of a drove of ponies her father had bought, argues the complicated point of where Chaney should be arrested with LaBoeuf, a Texas Ranger who joins on with Mattie and Rooster, and, finally, confronts Chaney himself in a classic Western stand-off at the end of the film.

Another of the film’s attractions revolves around the stellar performances. Steinfeld perfectly portrays the precocious Mattie, a character who ranges widely between innocent adolescence and stark adulthood. She effortlessly acts the little girl who likens following the trail of a dangerous killer in the wilds of Indian territory to camping out on a coon hunt with her father, and just as easily the adult horse trader, able to handle the seasoned Col. Stonehill, who ends up paying more than he would ever have paid to a less persistent customer to take back the horses he originally sold Mattie’s father. Bridges plays Cogburn with a joie de vivre that makes him seem exactly what he is supposed to be: a man with true grit, whose heart is won in the end by the endearing Mattie. Damon represents the dandy, stuck-on-himself LaBouef with a sympathetic humanity, letting his offensive side only show when it does not matter. The supporting cast, anchored by Josh Brolin as Chaney and Barry Pepper as Lucky Ned Pepper, are without exception superb, giving the audience just that blend of strange quirkiness and realistic toughness that characterizes the myth of the old West in the mind of the American moviegoer. It would be hard to name a film that has more consistent greatness of acting in every performance.

But story and acting admitted, the true success of the movie lies in its depth of moral character, demonstrated in all aspects of the film, from the dramatis personae, to the story line, to the noble, almost Shakespearean dialogue, to the lilting, hymn-based music. Everywhere the movie rests clearly on, and never departs from, its plain, noble center. In this, Grit resembles the remarkable novel by Charles Portis on which the film is based, and departs widely from the well-known earlier movie of the same name, the John Wayne starrer of 1969, which flies in the face of the novel and is far sunnier, and far weaker, than both the book and the Coen brothers picture.

What is that central truth? It is best summarized by a comment in the introductory voice-over by Mattie, but it is important to recognize that the stage is set for a deeper moral examination from the very beginning of the film. Eschewing credits almost entirely, the film begins with a simple card on a black background, presenting the first half of Proverbs 28:1 from the King James Version: “The wicked flee when none pursueth.” Very quietly a simple piano plays a few notes of the hymn “Leaning on the Everlasting Arms,” as an ethereal light grows into the scene of a porch with its stairs leading down to the body of a man, apparently lying dead in the street with snow gently covering him. Suddenly a man rides by on horseback, and the adult Mattie tells the viewer what has happened to precipitate the events we will watch unfold:

People do not give it credence that a young girl could leave home, and go off in the wintertime to avenge her father’s blood, but it did happen. I was just fourteen years of age, when a coward by the name of Tom Chaney shot my father down and robbed him of his life, and his horse, and two California gold pieces that he carried in his trouser band…

Chaney fled. He could have walked his horse for not a soul in that city could be bothered to give chase. No doubt Chaney fancied himself scot-free. But he was wrong. You must pay for everything in this world one way and another. There is nothing free except the grace of God.

Justice and grace are the foundation upon which the Coen brothers have built their film, and they have done so in a way rarely seen in Hollywood.

Not only does True Grit begin with a quotation from Proverbs, but the film refers to Scripture and homespun, frontier Christianity throughout. Mattie refers, for example, to sleeping in the same room with the three corpses at the undertaker’s as causing her to feel like Ezekiel in the valley of the dry bones. Perhaps the starkest reminder of this flavor of the film comes from the musical theme, based on the frontier hymn, “Leaning on the Everlasting Arms.” The film ends with a full-throated rendition of the hymn sung by the alternative country singer Iris Dement, and, as we have mentioned above, the same hymn is playing in the background, when Mattie delivers the central statement of the movie, which makes the film’s Christian roots quite clear: “You must pay for everything in this world, one way and another. There is nothing free except the grace of God.”

The specifically Christian themes are so many and so sympathetically introduced that one marvels at “Christian” movie-making being done once again by non-Christians (cf. the great Chariots of Fire). Nothing demonstrates this so much as the dialogue itself. Supporting characters regularly use Biblical language. Yarnell, Mattie’s servant, breathes a “Praise the Lord” after declaring that Mattie’s father has “gone home,” and even one of the criminals hanged at the beginning of the film encourages the audience with his last words to “train up your children in the way that they should go.” More significantly, Matt Damon’s LaBoeuf prays before he shoots Ned Pepper; just a brief invocation—“Oh, Lord” as he takes aim, knowing he has one shot at 400 yards or Rooster Cogburn is dead—but a reverent, humble prayer nonetheless. And it is answered positively; Ned Pepper falls before he can kill Rooster.

Christian themes are supported in other, more subtle ways. Once, when Rooster has two criminals holed up in a cabin, he calls out to them, asking who they are. They reply “a Methodist and a son of a bitch,” but later as Moon, the young Methodist, lies dying, he asks to be remembered to his brother, a Methodist “circuit rider.” Rooster is gentle with Moon, asking him if he wants Rooster to tell Moon’s brother that he died a criminal. Moon tells him it doesn’t matter, confidently declaring, “I will meet him later walking the streets of glory.”

The scene has a poignancy that appears heart-felt. This is especially noteworthy, given the Coen brothers’ penchant throughout their careers for sarcasm regarding religion. Rooster does sardonically end the scene by telling Moon when he gets to heaven not to be looking for Quincy (the other criminal who has murdered Moon for talking), but even this line is delivered with gentle violins in the background and without malice. The scene is a perfect example of the clear moral tone that undergirds virtually every scene in the film.

The lynchpin for the Christian framework of the film, however, resides in the complicated but wonderful depiction of the film’s central character, Mattie Ross. Peter Travers of Rolling Stone calls it “Presbyterian steel,” but Mattie’s demeanor is more subtle than that. Her perseverance on the one hand colors her character with an honor and self-sacrifice that awes the two older men, as it does the audience. She is the one with “true grit” in the end, able to fire at Tom Chaney point blank, and more than once. But Mattie can be read just as easily as a childish legalist-with-a-heart, and at points in the film it is hard to know what the Coen brothers intend in her character: a sympathetic portrait of a fundamentalist or a sarcastic portrayal of a naive idealist. After all, she does grow up into an old maid, who seems to have lived a cantankerous, lonely life, carrying with her the scar of her adventure in her stump of a left arm, but so certain of herself, she is not even likeable.

This uncertainty demonstrates how great Mattie’s character really is in this version of the story because believability and veneration are exactly the two qualities needed for a true movie hero, and both reside in Mattie. Mattie is the center of the movie, really, not Cogburn, unlike the 1969 version in which John Wayne took center stage. Her dogged pursuit of the criminal Tom Chaney, who shot her father, and the humor she brings in shaming men old enough to be her father, make the picture alive.

But what are we to think of Mattie’s quest: is she pursuing justice or only seeking revenge? The answer lies in reference to a theme that is scattered liberally through many films in 2010: family. Mattie’s desire to honor her father makes her continue on, no matter what the cost, and it is her perseverance that causes that pursuit to triumph. She loved her father and insists that Tom Chaney be punished at Fort Smith rather than in Texas (where LaBoeuf prefers him to be tried because LaBoeuf gets the reward, if he takes Chaney to Texas, and doesn’t if Chaney is hanged in Arkansas). Mattie of course doesn’t care about the money. But she reiterates time and again: “I do not want him to die in Texas for shooting the dog of a Senator. He must die in Arkansas because he shot my father.”

It is the honoring of her father that makes Mattie’s character a truly Christian one. She is not just a remarkably stubborn child, who will pursue a goal simply because she has chosen a path and is determined to walk it to the end. Although there are never any signs of doubt in her vision, that vision is one of love for her father and retribution for his death, which drives her noble actions, and the Christian understanding of grace and justice shines through them.

True Grit is a classic western with all the elements of the journey story. Both Rooster and Mattie (and LaBouef to some degree) develop in the movie, not just in our eyes as revealing character they already contained, but as changing, learning to trust others, learning humility, learning friendship. Even as they persevere in the face of repeated challenges, they begin to trust each other, realizing they cannot do alone everything worth doing in life. The film contains tender moments and rousing moments, grisly moments and beautiful moments, and the Coens master each wonderfully.

Most notable, though, is how Christian the film feels in every frame. The Coen brothers, Jewish by upbringing but admittedly irreligious in practice, have demonstrated that grace themselves, which Christians call “common grace,” in making this film so thoroughly enjoyable. As Armond White put it in his review in First Things: “Who knew America’s coolest filmmakers would turn out to be its most openly spiritual?”