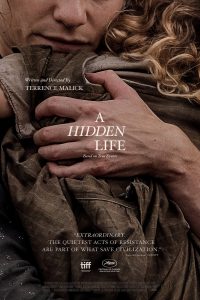

A Hidden Life (Terrence Malick, 2019)

A Hidden Life shouldn’t be hidden

“A darker time is coming,” we hear in Terrence Malick’s new film A Hidden Life. “Men will be more clever. They won’t fight the truth. They’ll just ignore it.”

Malick’s powerhouse film, which appeared in theaters just before Christmas 2019, has been called by several Christian critics one of the best cinematic depictions of the gospel. It tells the story of Franz Jägerstätter, an Austrian farmer who was ordered to military duty during WWII but refused to swear an oath of allegiance to Hitler. Between the beauty of the story and the brilliance of the filmmaking, A Hidden Life may well become what some consider one of our most treasured pieces of Christian art. In the wider culture, however, this movie might also be seen as a piece of art that won’t be so much challenged or ridiculed—it will just be ignored.

In 2011, Malick’s much less linear film but still infused with Christian themes, Tree of Life, was nominated for several Oscars. A Hidden Life was not only snubbed by the Oscars, but it appears to have confused and frustrated many critics and audiences. To date (the end of February 2020), the film has grossed $3.4 million dollars in a limited theater release. (To put that in perspective, Frozen II, which came out about the same time has made $1.43 billion in ticket sales.)

My hope is to convince you that this movie should not be ignored. A Hidden Life is certainly different—it’s like watching an I-Max nature film while listening to epic poetry, classical music, and sacred hymns. It’s nearly three hours long and uses lots of intimate wide-angle shots that shove you, often rather uncomfortably, into the personal space of the characters. It also brings up some pretty tough questions:

Is one justified to let their family suffer if it’s for a just cause?

At what point do you publicly protest against something in society you believe is unjust?

How do you discern whether it’s time to go down a path that could lead to martyrdom?

Just a bit of lite dinner table conversation. The film will challenge you, but if you allow yourself into its world, A Hidden Life will reward you with one of the most beautiful and inspiring stories of what it looks like to follow Jesus.

A Contrast

It is easier to understand what Malick is doing in A Hidden Life if we see this film as the third, final part of a series that include his last two movies, Knight of Cups (2015) and Song to Song (2017). Both stories are filmed in a twirling, stream-of-consciousness style, and attempt to give verisimilitude to the modern bourgeois lifestyle of wandering from “one desire to the next.” In one of his rare interviews, Malick described what he was depicting in these movies: “…you can live in this world just moment to moment, song to song, kiss to kiss… and try to create these different moods for yourself and go through the world… living one desire to the next, and where does that lead, what happens to you in that sort of [life]?”

The outwardly beautiful characters mingle with the rich and famous at the most chic and extravagant Los Angeles house parties, trying to spark excitement. The romantic leads are always brushing their hands together in ephemeral touches and twirling around one another aimlessly in giant modern houses made of glass. They seem as if they are just floating around one another like out-of-body spirits. Both movies get a little extreme in trying to capture this mood (one critic described it as “excessive, soft-core twirling”), but Malick shows how depressing it can be to try to find meaning in self-fulfillment. It would be sad if Malick’s message ended there. But like any good preacher, he is setting us up to hear the good news.

Compared to the modern urban despair of Knight of Cups and Song to Song, seeing the opening scenes of A Hidden Life is like ascending to an Alpine version of Eden. We meet Franz and his wife Fani Jägerstätter on their breathtakingly beautiful farm in the mountains playing with their children. Their hands—wedding bands prominent—mingle in the loamy earth as they bury seed potatoes. They roll together in the pasture and play “blind man’s bluff” with their little girls. Instead of the uncommitted, wispy touches that we see in the other two films, Franz and Fani linger in strong, full embraces, their bodies wrapped together as one.

It’s almost too perfect, but Malick wants us to see how the Jägerstätters’ life is beautifully rooted in their faith, land, and community. By their visible sweat and dirty faces, we see that things aren’t easy, but there is an undeniable harmony to their natural, earthy life compared to the ephemeral fogginess of the characters in Knight of Cups and Song to Song. And whereas those characters wander around aimlessly with no purpose, we quickly realize in A Hidden Lifethat the Jägerstätters not only have a clear purpose in life as followers of Jesus, but they will be called upon to live it out—no matter the cost. And as we watch the simple agrarian beauty of the couple’s life—the hard but satisfying manual labor, their tightly-knit village and church, their happy marriage and home—Malick shows us that the cost they will pay is so very high.

The Cost of Discipleship

“I thought we could build our nest high up, in the trees, fly away like birds to the mountains,” Franz whispers as the camera flies over their lusciously green valley. In his community, he is known for his outspoken contempt for the Nazis, but he is alone in his stand and is increasingly ostracized by his fellow villagers. “You are worse than the enemy,” the mayor of the town tells Franz. “You are a traitor!” Eventually Franz is summoned for military duty, and he knows it is only a matter of time before he will be forced to swear that Hitler is his highest authority. He can’t do it. His conscience won’t allow it. All his church and community leaders tell him to just keep his resistance in his heart, hidden away. “I cannot do what I believe is wrong,” he says.

At every step everyone keeps pressing him: You are only doing this out of pride. How can you know for sure what you are doing is right? Your sacrifice will benefit no one. You think you are so innocent? We all have blood on our hands. Even the bishop tells him, “Your duty is to your fatherland,” and recites Romans 13:1. But Franz is convinced that his ultimate allegiance is to Christ and he sees Hitler’s war as unjust. He sees himself as the rich young man in Matthew 10 who must decide whether or not to leave his great wealth behind and follow God’s call. “Go,” Jesus says to him, “sell all that you have and give to the poor, and you will have treasure in heaven; and come, follow me.” Franz’ wealth may not be exactly like the young man’s in the Gospel but in his agrarian and marital bliss, it is equally great.

If Franz was to listen to everyone telling him to take an easier way, he may have settled into a similar position as the Jesuit priest in the 2018 film Silence. He renounces Christ in a public ritual, accepting that what he believes hidden in his heart is more important than what he does on the outside. After seeing that movie, Malick apparently wrote a letter to the director, Martin Scorsese and asked, “What does Christ want from us?” With the story of Franz and Fani, Malick urges us back to the position of the apostle Paul and the martyrs who would not compromise. As Dietrich Bonhoeffer (who was in the same prison as Franz) wrote, “When Christ calls a man, he bids him come and die.”

One of the most striking scenes in A Hidden Life is Franz listening to an old church painter pontificating as he works on the frescoes in the local church. “I paint their comfortable Christ, with a halo on his head,” he says. “What we do is just create sympathy, create admirers… We don’t create followers.”

Franz and Fani certainly struggle to follow their Lord’s calling, and in their suffering, we see their connection and submission to God’s incarnate Word won’t allow them to be merely admirers. Unlike the Gnostic epistle of Silence,where the admirer is held up as the example, what we see in A Hidden Life is an ode to the profound obedience of committed followers.

This film will likely be ignored by many, but for those with ears to hear and eyes to see it is an unforgettable experience. It’s especially powerful because non-Christians have to acknowledge it is good art and believers have to wrestle with its high calling. So, find someone with a video projector or giant television and start planning the viewing party. The silver lining in the film’s lack of success in theaters is that hopefully we won’t have to wait long for the DVD release.

Copyright © 2020 Daniel Miller.

Questions for reflection and discussion:

- What was your initial or immediate reaction to the film? Why do you think you reacted that way?

- What emotions did you experience as you watched A Hidden Life? What scenes were most poignant to you? Why?

- In what ways were the techniques of filmmaking (casting, direction, lighting, script, music, sets, action, cinematography, editing, etc.) used to get the film’s message(s) across, or to make the message plausible or compelling? In what ways were they ineffective or misused?5. With whom did you identify in the film? Why? With whom were we meant to identify? Discuss each main character in the film and their significance to the story.

- Do you agree with Daniel Miller that A Hidden Life contains distinctly Christian themes? Under what conditions should we be willing to speak of a film like this being a “Christian film”? Is it helpful in today’s pluralistic world to talk about it in such terms? Why or why not?

- Miller is concerned that A Hidden Life is being hidden or ignored compared to other more popular movies. What other reasons, besides its Christian themes, might non-Christian or nominal Christian movie viewers have for not being drawn to see A Hidden Life?

- A Hidden Life tells a story that depicts what Christ was referring to when he spoke of the cost involved in following him. Consider, for example, Matthew 16:24-26: “If anyone would come after me, let him deny himself and take up his cross and follow me. For whoever would save his life will lose it, but whoever loses his life for my sake will find it. For what will it profit a man if he gains the whole world and forfeits his soul? Or what shall a man give in return for his soul?” (This teaching of Jesus is repeated in Mark 8:34 and Luke 9:23.) The Lord states the issue in even starker terms in Matthew 10:38: “…whoever does not take his cross and follow me is not worthy of me…” and in Luke 14:27: “Whoever does not bear his own cross and come after me cannot be my disciple.”

This isn’t a particularly popular theme and is often assumed to apply primarily to people in other eras (like those living under the Babylonians, Nazis or Soviets) or in non-Western countries (like Saudi Arabia or the Sudan) or in extreme circumstances (like warfare, terrorism or massive natural disasters). Or sometimes it is reduced to meaning that we must remain cheerful in hard times like illness or the aftermath of some tragedy. A minority of believers commit civil disobedience by withholding some of their taxes that would go towards defense (in the name of pacifism) or in order to protest against abortion.

With all this in mind, consider these questions: To what extent is your faith comfortable rather than costly? In what specific ways do you deny yourself and take up your cross in order to follow Christ? To what extent is this daily, as Christ said it should be? In this time of political uncertainty, rapid change and polarization what issues might require Christians to engage in civil disobedience, even at cost?

(Questions by Denis Haack)

Film credits: A Hidden Life

Director: Terrence Malick

Writer: Terrence Malick

Music: James Newton Howard

Cinematography: Jörg Widmer

Starring:

August Diehl (Franz Jägerstätter)

Valerie Pachner (Fani Jägerstätter)

Karl Markovics (Mayor Kraus)

Bruno Ganz (Judge Lueben)

Michael Nyqvist (Bishop Fliesser)

Matthias Schoenaerts (Herder)

Jürgen Prochnow (Major Schlegel)

Bruno Ganz (Richter)

Alexander Fehling (Fredrich Feldmann)

Ulrich Matthes (Lorenz Schwaninger)

Fox Searchlight Pictures; 2019

2 hours 54 minutes (174 minutes)

PG-13 (for thematic material including violent images)