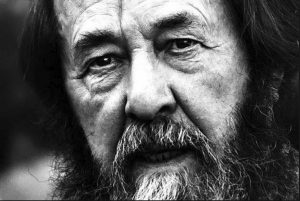

It was his novels–One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich (1962) and Cancer Ward (1968)–that probed most deeply into my heart and imagination. Scenes and conversations from both flash into my mind whenever Solzhenitsyn’s name is mentioned. His massive, three volume Gulag Archipelago (1973-1978) was not easy reading but impossible to put down, convincing me that justice requires giving voice to the nameless that have suffered far from the front pages of historical reporting. The photo included here, by the way is his Gulag mugshot, taken in 1953 when he began his sentence in the hard labor prison camp in Siberia.

And then there were two speeches that he gave that I will never forget. Reading them today reminds me that they seem dated, so deeply did they address the cultural, political, and spiritual realities of their historical moment. If you take time to read them now, keep that in mind. And here are two brief excerpts–both rather timeless in their message–to give you a flavor of the thinking of a man whose passion for truth was unrelenting.

From “Men Have Forgotten God,” Alexander Solzhenitsyn’s Templeton Prize speech (May 10, 1983, emphasis in original):

More than half a century ago, while I was still a child, I recall hearing a number of older people offer the following explanation for the great disasters that had befallen Russia: Men have forgotten God; that’s why all this has happened.

Since then I have spent well-nigh fifty years working on the history of our Revolution; in the process I have read hundreds of books, collected hundreds of personal testimonies, and have already contributed eight volumes of my own toward the effort of clearing away the rubble left by that upheaval. But if I were asked today to formulate as concisely as possible the main cause of the ruinous Revolution that swallowed up some sixty million of our people, I could not put it more accurately than to repeat: Men have forgotten God; that’s why all this has happened.

What is more, the events of the Russian Revolution can only be understood now, at the end of the century, against the background of what has since occurred in the rest of the world. What emerges here is a process of universal significance. And if I were called upon to identify briefly the principal trait of the entire twentieth century, here too, I would be unable to find anything more precise and pithy than to repeat once again: Men have forgotten God.

From “A World Split Apart,” a commencement speech given at Harvard (June 8, 1978):

Western society has given itself the organization best suited to its purposes, based, I would say, on the letter of the law. The limits of human rights and righteousness are determined by a system of laws; such limits are very broad. People in the West have acquired considerable skill in using, interpreting and manipulating law, even though laws tend to be too complicated for an average person to understand without the help of an expert. Any conflict is solved according to the letter of the law and this is considered to be the supreme solution. If one is right from a legal point of view, nothing more is required, nobody may mention that one could still not be entirely right, and urge self-restraint, a willingness to renounce such legal rights, sacrifice and selfless risk: it would sound simply absurd. One almost never sees voluntary self-restraint. Everybody operates at the extreme limit of those legal frames. An oil company is legally blameless when it purchases an invention of a new type of energy in order to prevent its use. A food product manufacturer is legally blameless when he poisons his produce to make it last longer: after all, people are free not to buy it.

I have spent all my life under a communist regime and I will tell you that a society without any objective legal scale is a terrible one indeed. But a society with no other scale but the legal one is not quite worthy of man either. A society which is based on the letter of the law and never reaches any higher is taking very scarce advantage of the high level of human possibilities. The letter of the law is too cold and formal to have a beneficial influence on society. Whenever the tissue of life is woven of legalistic relations, there is an atmosphere of moral mediocrity, paralyzing man’s noblest impulses.

And it will be simply impossible to stand through the trials of this threatening century with only the support of a legalistic structure.