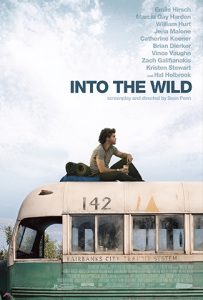

Into the Wild

(Sean Penn, 2007)

Some movies are like cotton candy, others like granola. Some are sweet but vacuous; others more demanding but more nutritious. Sean Penn’s cinematic adaptation of Jon Krakauer’s book is of the latter version. It’s a granola film designed for prolonged reflection and meaningful discussion. Viewers or reviewers who easily dismiss the poignancy of the film’s existential journey only reveal the superficiality of their souls.

Into the Wild tells the true story of Chris McCandless, an Emory University honors graduate, who embarks on a two-year sojourn that ends in his death in the Alaskan wilderness. It is an epic tale of a life stripped bare of its modern nonessentials in a desperate search for what really matters. It ends with an epiphany at the moment of personal tragedy. Into the Wild is a cautionary tale for those trapped by the superficial and self-indulgent, for those whose suburban alchemy turns the American Dream into the search for the Holy Grail. The meaning of life is not here. But neither is it to be found in the Alaskan wilderness—as the poetic outdoorsman discovers in his dying aloneness.

The film is a marked achievement for writer/director Sean Penn. Shot on locations that track McCandless’ cross-country odyssey, the magnetism and menace of nature is beautifully portrayed. In tandem with cinematographer Eric Gautier (The Motorcycle Diaries), Penn uses the physical landscape as a backdrop to McCandless’ spiritual soulscape. Emile Hirsch’s performance (The Lords of Dogtown) as McCandless captures his sense of anger, arrogance, and adventure with depth and sensitivity. A varied and talented supporting cast complement Hirsch. Hal Holbrook, as widower Ron Franz, was nominated for an Academy Award. One can quibble with the film’s length (two hours and twenty-eight minutes), its use of voice over (McCandless’ sister, Carine, provides the familial back story), and its musical overuse of Eddie Vedder. But little mars the over all scope of the film’s epic journey and the character arch of its protagonist’s tragic epiphany. The film grips you and does not let you go.

The film is a marked achievement for writer/director Sean Penn. Shot on locations that track McCandless’ cross-country odyssey, the magnetism and menace of nature is beautifully portrayed. In tandem with cinematographer Eric Gautier (The Motorcycle Diaries), Penn uses the physical landscape as a backdrop to McCandless’ spiritual soulscape. Emile Hirsch’s performance (The Lords of Dogtown) as McCandless captures his sense of anger, arrogance, and adventure with depth and sensitivity. A varied and talented supporting cast complement Hirsch. Hal Holbrook, as widower Ron Franz, was nominated for an Academy Award. One can quibble with the film’s length (two hours and twenty-eight minutes), its use of voice over (McCandless’ sister, Carine, provides the familial back story), and its musical overuse of Eddie Vedder. But little mars the over all scope of the film’s epic journey and the character arch of its protagonist’s tragic epiphany. The film grips you and does not let you go.

To the outward observer, Chris begins the film filled with youthful promise: academic achievement, graduate opportunities, career prospects, and adoring, if demanding, family. But no one’s life is as it appears. Neither is Chris’. Beneath his veneer of middle class aspiration and expectation lies a deep-seated anger and restlessness. With monomaniacal courage, he abandons it all—his prospects, his prosperity, and most importantly his parents. “Rather than love, than money, than faith, than fame, than fairness…give me truth,” he declares. There is something noble, even spiritually heroic in his relentless search for truth.

The romantic wayfarer strikes out unencumbered by the dictates and distractions of suburban life into the mythic salvation of solitude and nature. On his journeys he observes and critiques the lives of others. He perceptively identifies the hidden pain in everyone else but himself. And yet, his knowledge of others is never joined with empathy, for he is hardened against the possibility of love. “Some people feel like they don’t deserve love. They walk away quietly into empty spaces, trying to close the gaps of the past,” he observes.

What Chris fails to acknowledge is that his risk-taking is fueled by anger; his adventurous spirit is an escape from self-reflection. “The core of man’s spirit comes from new experiences.” Sensitive and social, his outward persona is at odds with his inner demons… and so he keeps moving lest attachments to others expose his deepest fears.

Like all romantics, he blames others—the constraints of convention—society with its parents, hypocrites, politicians, and pricks. The wilderness by contrast is pure and primal.

Alaska, Alaska. I’m gonna be all the way out there, all the way f*cking out there. Just on my own. You know, no f*cking watch, no map, no axe, no nothing. No nothing. Just be out there. Just be out there in it. You know, big mountains, rivers, sky, game. Just be out there in it, you know? In the wild.

Chris is in love with Nature. “You don’t need human relationships to be happy. God has placed it all around us.” Penn makes the pantheist’s case just as strongly as one can make it. The physical power of raging rivers, the vistas from mountain summits, the stars in a cloudless sky, and the majesty of snowcapped peaks are the visual sirens of McCandless’ inner odyssey.

Chris read Henry David Thoreau and Jack London. He should have added Steven Crane:

A man said to the universe,

Sir, I exist!

Nevertheless, replied the universe,

That fact has not created in me

The slightest feeling of obligation.

One can embrace Nature, but it will not return the embrace. The universe like Rhett Butler turns on those who embrace her and says, “Frankly, my dear, I don’t give a damn.” G. K. Chesterton adds, “A man loves Nature in the morning for her innocence and amiability, and at nightfall, if he is loving her still, it is for her darkness and her cruelty.”

And so the berries are not food, but poison. In the midst of his slow solitary starvation, Chris acknowledges the spiritual blockage to his metaphysical blindness. He has abandoned love because he cannot forgive those who should have loved him but did not. The aging widower warns him prior to his trek into the wild, but he does not have ears to hear: “When you forgive, you love. And when you love, God’s light shines upon you.”

What really matters, when life is stripped of everything else, is relationships. Nature is not enough. It is not Nature that points beyond itself, but Creation. And so Chris scrawls his epiphany in the leaves of a book: “Happiness is only real when shared.” It is love we seek—even when it demands the forgiveness we resist. As he closes his eyes in death, he envisions the embrace of his parents. “What if I were smiling and running into your arms? Would you see then what I see now?”

How far will we have to run? How many layers will we peel away before we acknowledge that the search for truth leads to the reality of love? To have searched and died knowing is more heroic than to have never searched at all.

Copyright © 2008 David John Seel.

Into the Wild credits:

Starring:

Emile Hirsch (Chris McCandless)

Marcia Gay Harden (Billie McCandless)

William Hurt (Walt McCandless)Into the Wild credits:

Jena Malone (Carine McCandless)

Brian Dierker (Rainey, as Brian Dierker)

Catherine Keener (Jan Burres)

Vince Vaughn (Wayne Westerberg)

Hal Holbrook (Ron Franz)

Kristen Stewart (Tracy Tatro)

Director: Sean Penn

Writers: Sean Penn (screenplay); Jon Krakauer (book)

Producers: David Blocker, Frank Hildebrand, John J. Kelly, Sean Penn

Original Music: Michael Brook, Kaki King, Eddie Vedder

Cinematographer: Eric Gautier

Runtime: 148 minutes

Release: USA; 2007

Rated R (for language and some nudity)